Woah, I just read some of the responses to Dunn et al. (2011) “Evolved structure of language shows lineage-specific trends in word-order universals” (language log here, Replicated Typo coverage here). It’s come in for a lot of flack. One concern raised at the LEC was that, considering an extreme interpretation, there may be no affect of universal biases on language structure. This goes against Generativist approaches, but also the Evolutionary approach adopted by LEC-types. For instance, Kirby, Dowman & Griffiths (2007) suggest that there are weak universal biases which are amplified by culture. But there should be some trace of universality none the less.

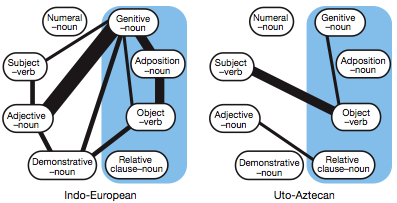

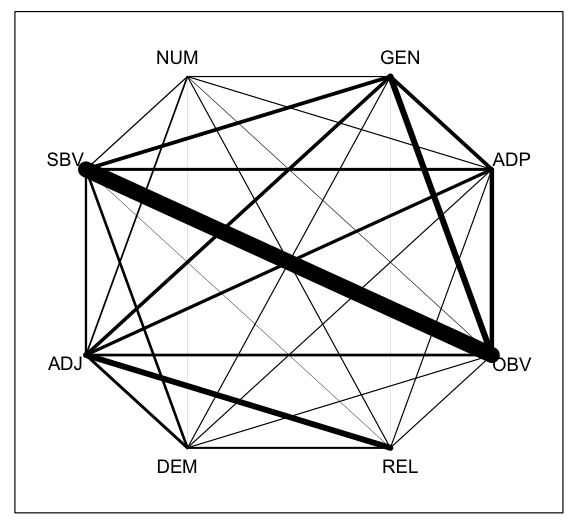

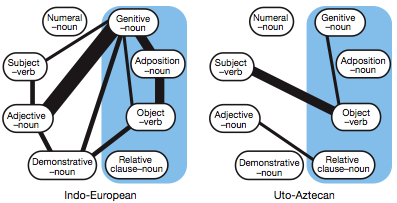

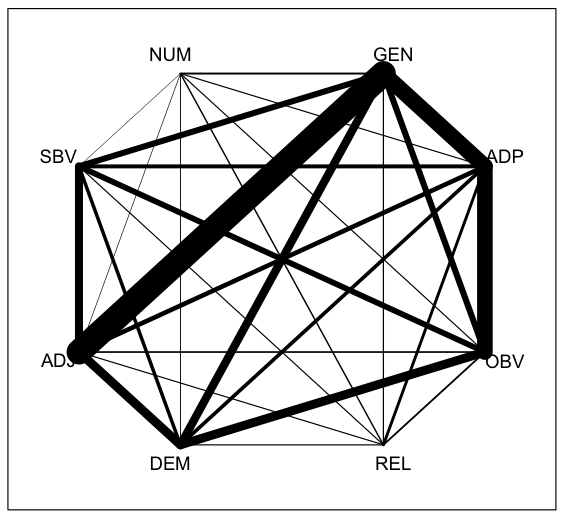

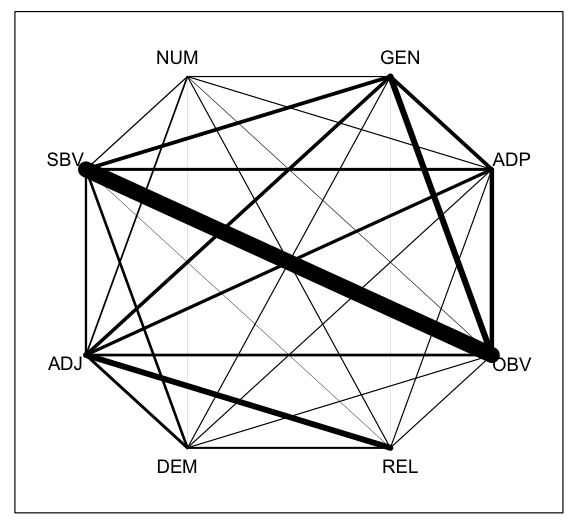

Below is the relationship diagram for Indo-European and Uto-Aztecan feature dependencies from Dunn et al.. Bolder lines indicate stronger dependencies. They appear to have different dependencies- only one is shared (Genitive-Noun and Object-Verb).

However, I looked at the median Bayes Factors for each of the possible dependencies (available in the supplementary materials). These are the raw numbers that the above diagrams are based on. If the dependencies’ strength rank in roughly the same order, they will have a high Spearman rank correlation.

| Spearman Rank Correlation |

Indo-European |

Austronesian |

| Uto-Aztecan |

0.39, p = 0.04 |

0.25, p = 0.19 |

| Indo-European |

|

-0.13, p = 0.49 |

Spearman rank correlation coefficients and p-values for Bayes Factors for different dependency pairs in different language families. Bantu was excluded because of missing feature data.

Although the Indo-European and Uto-Aztecan families have different strong dependencies, have similar rankings of those dependencies. That is, two features with a weak dependency in an Indo-European language tend to have a weak dependency in Uto-Aztecan language, and the same is true of strong dependencies. The same is true to some degree for Uto-Aztecan and Austronesian languages. This might suggest that there are, in fact, universal weak biases lurking beneath the surface. Lucky for us.

However, this does not hold between Indo-European and Austronesian language families. Actually, I have no idea whether a simple correlation between Bayes Factors makes any sense after hundreds of computer hours of advanced phylogenetic statistics, but the differences may be less striking than the diagram suggests.

UPDATE:

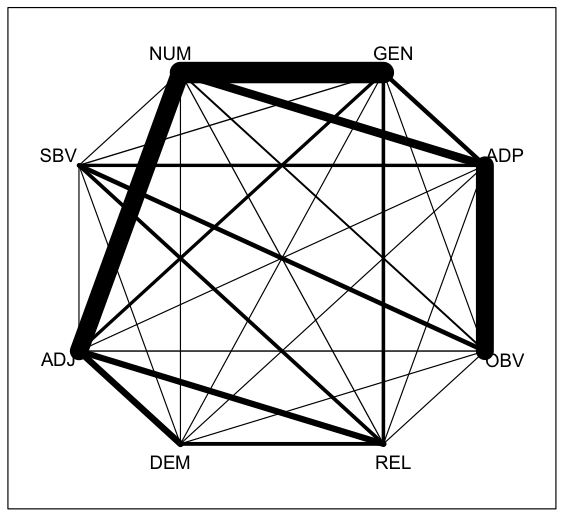

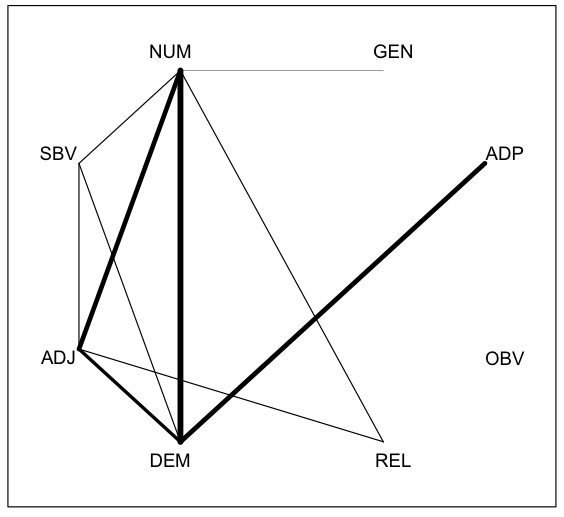

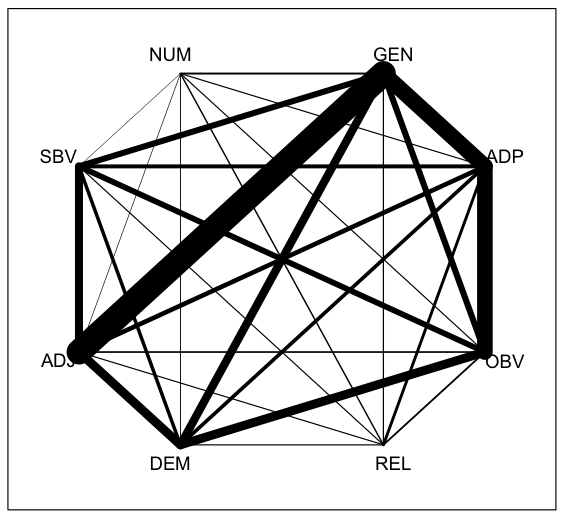

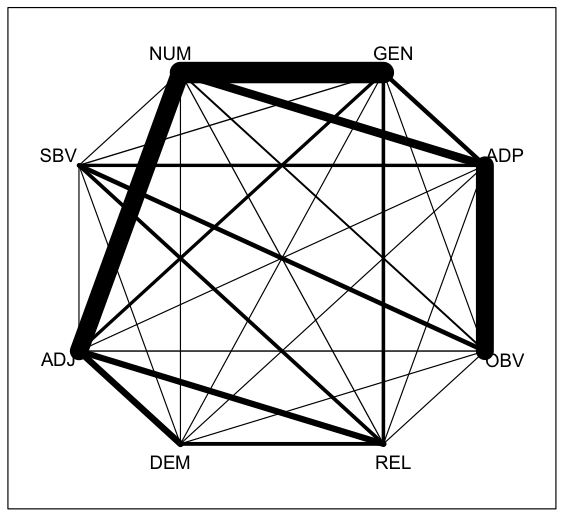

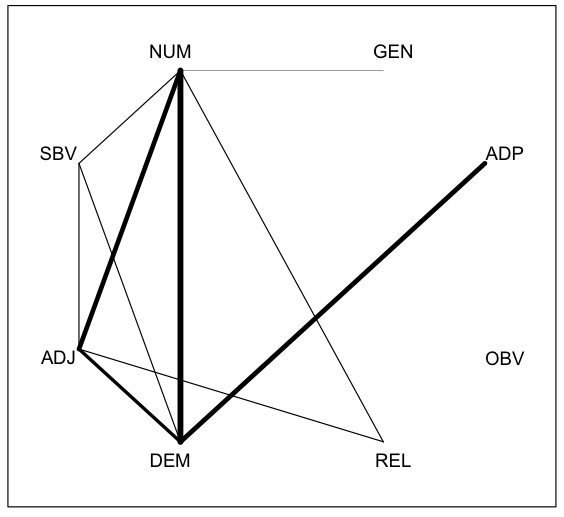

As Simon Greenhill points out below, the statistics are not at all conclusive. However, I’m adding the graphs for all Bayes Factors (these are made directly from the Bayes Factors in the Supplementary Material):

Austronesian: Bantu:

Indo-European: Uto-Aztecan:

Michael Dunn,, Simon J. Greenhill,, Stephen C. Levinson, & & Russell D. Gray (2011). Evolved structure of language shows lineage-specific trends in word-order universals Nature, 473, 79-82

In what is sure to be a more cited paper than Gould and Lewontin (1979), Douglas Ochs at Columbia University, together with a team of internationally renowned scientists (and probably a few internationally unknown graduate students), has found that all of humanity can be traced back to a large Pliocene-era goat.

In what is sure to be a more cited paper than Gould and Lewontin (1979), Douglas Ochs at Columbia University, together with a team of internationally renowned scientists (and probably a few internationally unknown graduate students), has found that all of humanity can be traced back to a large Pliocene-era goat.