Hello! This is my first post here at Replicated Typo and I thought I’d start with reposting a slightly modified version of a three-part series on the evolution of the human mind that I did last year over at my blog Shared Symbolic Storage.

So in this and my next posts I will have a look at how human cognition evolved from the perspective of cognitive science, especially ‘evolutionary linguistics,’ comparative psychology and developmental psychology.

In this post I’ll focus on the evolution of the human brain.

Human Evolution

We are evolved primates. (As are all other primates of course. So maybe it is better to say that we, like all other primates, are evolved beings with a unique set of specializations, adaptations and features. )

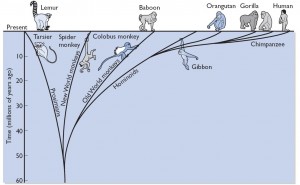

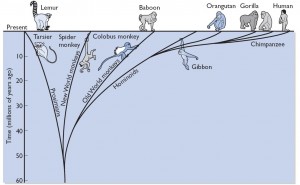

In our lineage, we share a common ancestor with orangutans (about 15 million years ago (mya)), gorillas (about 10mya), and most recently, chimpanzees and bonobos (5 to 7 mya). We not only share a significant amount of DNA with our primate cousins, but also major anatomical features (Gazzaniga 2008: 51f., Lewin 2005: 61) These include, for example, our basic skeletal anatomy, our facial muscles, or our fingernails (Lewin 2005: 218ff.).

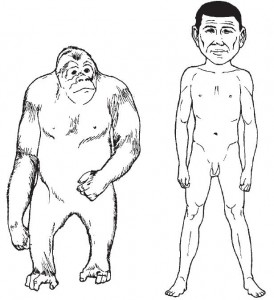

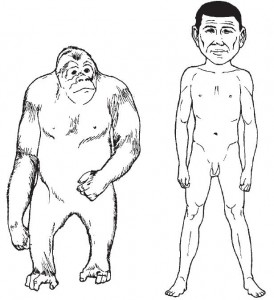

What most distinguishes us as humans on an anatomical level are our bizarre hair distribution, our upright posture and the skeletal modifications necessary for it, including a propensity for endurance running, our opposable thumbs, fat deposits that are unusually extensive (Preuss 2004: 5), and an intestinal tract only 60% the size expected of primates our size (Gibbons 2007: 1558).

Finally, there is also a distinguishing feature that is a much more remarkable violation of expectations – a brain three times the size expected of a primate our size. This is all the more interesting as primates are already twice as encephalized as other mammals (Lewin 2005: 217). A direct comparison shows this difference in numbers: Whereas human brains have an average volume of 1251.8 cubic centimetres and weigh about 1300 gram, the brains of the other great apes only have an average volume of 316.7 cubic centimetres and weigh between 350-500 gram (Rilling 2006: 66, Preuss 2004: 8). In a human brain, there are approximately a hundred billion neurons, each of which is connected to about one thousand other neurons, comprising about one hundred trillion synaptic connections (Gazzaniga 2008: 291). If you would count all the connections in the napkin-sized cortex alone, you’d only be finished after 32 million years (Edelman 1992: 17).

Finally, there is also a distinguishing feature that is a much more remarkable violation of expectations – a brain three times the size expected of a primate our size. This is all the more interesting as primates are already twice as encephalized as other mammals (Lewin 2005: 217). A direct comparison shows this difference in numbers: Whereas human brains have an average volume of 1251.8 cubic centimetres and weigh about 1300 gram, the brains of the other great apes only have an average volume of 316.7 cubic centimetres and weigh between 350-500 gram (Rilling 2006: 66, Preuss 2004: 8). In a human brain, there are approximately a hundred billion neurons, each of which is connected to about one thousand other neurons, comprising about one hundred trillion synaptic connections (Gazzaniga 2008: 291). If you would count all the connections in the napkin-sized cortex alone, you’d only be finished after 32 million years (Edelman 1992: 17).

Expensive Tissue

The human brain is also extremely “expensive tissue” (Aiello & Wheeler 1995): Although it only accounts for 2% of an adult’s body weight, it accounts for 20-25% of an adult’s resting oxygen and energy intake (Attwell & Laughlin 2001: 1143). In early life, the brain even makes up for up 60-70% of the body’s total energy requirements. A chimpanzee’s brain, in comparison, only consumes about 8-9% of its resting metabolism (Aiello & Wells 2002: 330). The human brain’s energy demands are about 8 to 10 times higher than those of skeletal muscles (Dunbar & Shultz 2007: 1344), and, in terms of energy consumption, it is equal to the rate of energy consumed by leg muscles of a marathon runner when running (Attwell & Laughlin 2001: 1143). All in all, its consumption rate is only topped by the energy intake of the heart (Dunbar & Shultz 2007: 1344).

Consequently, if we want to understand the evolutionary trajectory that led to human cognition there is the problem that

“because the cost of maintaining a large brain is so great, it is intrinsically unlikely that large brains will evolve merely because they can. Large brains will evolve only when the selection factor in their favour is sufficient to overcome the steep cost gradient“ (Dunbar 1998: 179).

This is especially important for people who want to come up with an “adaptive story” of how our brain got so big: they have to come up with a strong enough selection pressure operative in the Pleistocene “environment of evolutionary adaptedness” that would have allowed such “expensive tissue” to evolve in the first place (Bickerton 2009: 165f.).

What About the Brain is Uniquely Human?

If we look to the brain for possible hints, we first find that presently, there is “no good evidence that humans do, in fact, possess uniquely human cortical areas” (although the jury is still out) (Preuss 2004: 9). In addition, we find that there are functions specific to humans which are represented in areas homologous to areas of other primates. Instead, it seems that in the course of human evolution some of the areas of the brain expanded disproportionally, “especially higher-order cortical areas, including the prefrontal cortex” (Preuss 2004: 9, Deacon 1998: 435-438). This means that humans are not simply ‘better’ at thinking than other animals, but that they think differently (Preuss 2004: 7). The expansion and apparent specializations of only certain kinds of neuronal areas could indicate a qualitative shift in neuronal activity brought about by re-organization of existing features, leading to a wholly different style of cognition (Deacon 1998: 435-438 Rilling 2006: 75).

This scenario squares well with what we know about the way evolution works, namely that it always has to work with the raw materials that are available, and constantly co-opts and tinkers with existing structures, at times producing haphazard, cobbled-together, but functional results (Gould & Lewontin 1979, Gould & Vrba 1982). Given the relatively short time span for the evolution of the “most complex structure in the know universe”, as it is sometimes referred to, we have to acknowledge how preciously little time the evolutionary process had for ‘debugging.’ It could well be that make the human mind is so unique because it is an imperfect ‘Kluge:’ “a clumsy or inelegant – yet surprisingly effective – solution to a problem,” like the Apollo 13 CO2 filter or an on-the-spot invention by MacGyver (Marcus 2008: 3f.). It may thus well turn out that what we think makes us so special is a mental “oddity of our species’ way of understanding” the world around us (Povinelli & Vonk 2003: 160). It is reasonable then to assume that human cognition did not just simply get better across the board, but that instead we owe our unique style of thinking to quite specific specializations of the human mind.

With this in mind, we can now ask the question how these neurological differences must translate into psychological differences. But this is where the problem starts: Which features really distinguish us as humans and which are more derivative than others? A true candidate for what got uniquely human cognition off the ground has to pass this test and solve the problem how such “expensive tissue” could evolve in the first place.

In my next post I will have a look at six candidates for what makes human cognition unique.

References:

Aiello, L., & Wheeler, P. (1995). The Expensive-Tissue Hypothesis: The Brain and the Digestive System in Human and Primate Evolution Current Anthropology, 36 (2) DOI: 10.1086/204350

Aiello, L., & Wells, J. (2002). ENERGETICS AND THE EVOLUTION OF THE GENUS HOMO Annual Review of Anthropology, 31 (1), 323-338 DOI: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.31.040402.085403

Attwell, David and Simon B. Laughlin. (2001.) “An Energy Budget for Signaling in the Grey Matter of the Brain.” Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 21:1133–1145.

Bickerton, Derek (2009): Adams Tongue: How Humans Made Language. How Language Made Humans. New York: Hill and Wang.

Deacon, Terrence William (1997). The Symbolic Species. The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain. New York / London: W.W. Norton.

Dunbar, Robin I.M. (1998): “The Social Brain Hypothesis Evolutionary Anthropology 6: 178-190.

Dunbar, R., & Shultz, S. (2007). Evolution in the Social Brain Science, 317 (5843), 1344-1347 DOI: 10.1126/science.1145463

Edelman, Gerald Maurice (1992) Bright and Brilliant Fire: On the Matters of the Mind. New York: Basic Books

Gazzaniga, Michael S. (2008): Human: The Science of What Makes us Unique. New York: Harper-Collins.

Gibbons, Ann. (2007) “Food for Thought.” Science 316: 1558-1560.

Gould, Stephen Jay and Richard Lewontin (1979): “The spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian paradigm: a critique of the adaptationist programme.” Proclamations of the Royal. Society of London B: Biological Sciences 205 (1161): 581–98.

Gould, Stephen Jay, and Elizabeth S. Vrba (1982), “Exaptation — a missing term in the science of form.” Paleobiology 8 (1): 4–15.

Lewin, Roger (2005): Human Evolution: An Illustrated Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.

Marcus, Gary (2008): Kluge: The Haphazard Evolution of the Human Mind. London: Faber and Faber.

Povinelli, Daniel J. and Jennifer Vonk (2003): “Chimpanzee minds: Suspiciously human?” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7.4, 157–160.

Preuss Todd M. (2004): What is it like to be a human? In: Gazzaniga MS, editor. The Cognitive Neurosciences III, Third Edition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press: 5-22.

Rilling, J. (2006). Human and nonhuman primate brains: Are they allometrically scaled versions of the same design? Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 15 (2), 65-77 DOI: 10.1002/evan.20095

![]()

![]() When looking at culture-driven population dynamics, a common assumption is that there’s a positive feedback between cultural evolution and demographic growth. The general prediction, then, is for unlimited growth in population and culture. Yet models based on these assumptions tend to ignore important aspects of cultural evolution, namely: (1) cultural transmission is not perfect; (2) culture does not always promote population growth. Ghirlanda et al (2010) incorporate these two features into a model, and arrive at some interesting conclusions. In particular, they argue those populations maintaining large amounts of culture may run the risk of extinction rather than stability or growth.

When looking at culture-driven population dynamics, a common assumption is that there’s a positive feedback between cultural evolution and demographic growth. The general prediction, then, is for unlimited growth in population and culture. Yet models based on these assumptions tend to ignore important aspects of cultural evolution, namely: (1) cultural transmission is not perfect; (2) culture does not always promote population growth. Ghirlanda et al (2010) incorporate these two features into a model, and arrive at some interesting conclusions. In particular, they argue those populations maintaining large amounts of culture may run the risk of extinction rather than stability or growth.