What makes humans unique? This never-ending debate has sparked a long list of proposals and counter-arguments and, to quote from a recent article on this topic,

What makes humans unique? This never-ending debate has sparked a long list of proposals and counter-arguments and, to quote from a recent article on this topic,

“a similar fate most likely awaits some of the claims presented here. However such demarcations simply have to be drawn once and again. They focus our attention, make us wonder, and direct and stimulate research, exactly because they provoke and challenge other researchers to take up the glove and prove us wrong.” (Høgh-Olesen 2010: 60)

In this post, I’ll focus on six candidates that might play a part in constituting what makes human cognition unique, though there are countless others (see, for example, here).

One of the key candidates for what makes human cognition unique is of course language and symbolic thought. We are “the articulate mammal” (Aitchison 1998) and an “animal symbolicum” (Cassirer 2006: 31). And if one defining feature truly fits our nature, it is that we are the “symbolic species” (Deacon 1998). But as evolutionary anthropologists Michael Tomasello and his colleagues argue,

“saying that only humans have language is like saying that only humans build skyscrapers, when the fact is that only humans (among primates) build freestanding shelters at all” (Tomasello et al. 2005: 690).

Language and Social Cognition

According to Tomasello and many other researchers, language and symbolic behaviour, although they certainly are crucial features of human cognition, are derived from human beings’ unique capacities in the social domain. As Willard van Orman Quine pointed out, language is essential a “social art” (Quine 1960: ix). Specifically, it builds on the foundations of infants’ capacities for joint attention, intention-reading, and cultural learning (Tomasello 2003: 58). Linguistic communication, on this view, is essentially a form of joint action rooted in common ground between speaker and hearer (Clark 1996: 3 & 12), in which they make “mutually manifest” relevant changes in their cognitive environment (Sperber & Wilson 1995). This is the precondition for the establishment and (co-)construction of symbolic spaces of meaning and shared perspectives (Graumann 2002, Verhagen 2007: 53f.). These abilities, then, had to evolve prior to language, however great language’s effect on cognition may be in general (Carruthers 2002), and if we look for the origins and defining features of human uniqueness we should probably look in the social domain first.

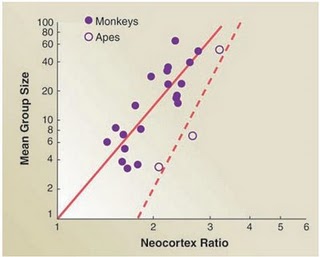

Corroborating evidence for this view comes from comparisons of brain size among primates. Firstly, there are significant positive correlations between group size and primate neocortex size (Dunbar & Shultz 2007). Secondly, there is also a positive correlation between technological innovation and tool use – which are both facilitated by social learning – on the one hand and brain size on the other (Reader and Laland 2002). Our brain, it seems, is essential a “social brain” that evolved to cope with the affordances of a primate social world that frequently got more complex (Dunbar & Shultz 2007, Lewin 2005: 220f.).

Thus, “although innovation, tool use, and technological invention may have played a crucial role in the evolution of ape and human brains, these skills were probably built upon mental computations that had their origins and foundations in social interactions” (Cheney & Seyfarth 2007: 283).

Continue reading “What Makes Humans Unique? (II): Six Candidates for What Makes Human Cognition Uniquely Human”