Are there more differences or more similarities between human language and other animal communication systems? And what exactly does it tell us if we find precursors and convergent evolution of aspects similar to human language? These were some of the key questions at this year’s Evolang’s Animal Communication and Language Evolution Workshop (proceedings for all workshops here).

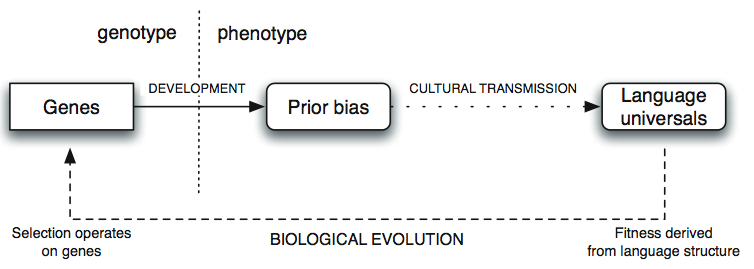

As Johan Bolhuis pointed out, ever since Darwin (1871), comparing apes and humans’ seemed like the most logical thing to do when trying to find out more about the evolution of traits presumed to be special to humans. Apes and especially chimpanzees, so the reasoning goes, are after all our closest relatives and serve as the best models for the capacities of our prelinguistic hominid ancestors. The comparative aspects of language have gained new attention since the controversial Hauser, Chomsky, Fitch (2002) paper in Science. For example, their claim that the capacity for producing and understanding recursive embedding of a certain kind is uniquely human was taken up by some researchers (including Hauser and Fitch themselves) who looked for syntactic abilities in other animals. More recently, songbirds have also become a centre of attention in the animal communication literature, with pretty much everything being quite controversial, however.

What is important here, according to the second workshop organizer Kazuo Okanoya, is that when doing research and theorizing, we should not treat humans as a special case, but as on a continuum with animals. And this also holds for language. In explaining language evolution, we don’t want to speak of a sudden burst that gave us something that is wholly different from anything else in the animal kingdom, but more of a continuous transition and emergence of language. For this it is, important to study other animals in closer details if we are to arrive at a continuous explanation of language emergence. Granted, humans are special. But simply saying they are special isn’t scientific. We need to detail in what ways humans are special.

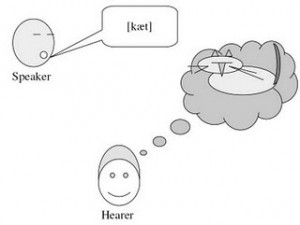

Regarding the central question whether there are more differences or similarities between language and animal communication, and what exactly these similarities and differences are, opinions of course differ. After the first speaker didn’t turn up Irene Pepperberg gave an impromptu talk on her work with parrots. Taking the example of a complex exclusion task, she argued that symbol-trained animals can do things other animals simply cannot, and that this might be tied to the complex cognitive processing that occurs during language (and vocal) learning. She also stressed that birds can serve as good models for the evolution of some aspects underlying language because they developed broadly similar vocal learning capacities like humans in a process referred to as parallel evolution, convergence, or analogy. Responding to other prevalent criticism, Pepperberg counters the view that animals like Alex and Kanzi are simply exceptional and unique, just like not every human is a Picasso or a Beethoven. What Picasso and Beethoven show us is what humans can be capable of, and the same holds for animals and Alex and Kanzi. No one would argue that animals have language in the sense that humans do. But given that they have the brain structures and cognitive capacities to allow a more complicated vocal learning and complicated cognitive processing means we can use them as a model of how these processes might have got started. There is still much work to be done, especially questions like what animals like parrots actually need and use these complex vocal and cognitive capacities for in the wild.

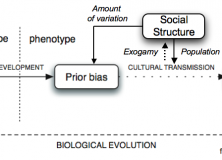

Whereas Dominic Mitchell argued in his talk that there is indeed a discontinuity between animal communication and human language with reference to animal signaling theory (e.g. Krebs & Dawkins 1984), Ramon Ferrer-i-Cancho after him focused more on the similarities. Specifically, he showed quite convincingly that statistical patterns in language, like Zipf’s law, the law of brevity, the law that more frequent words are shorter, and the Menzerath-Altmann law (the longer the words the shorter the syllables) can also be found in the communicative behaviours of other animals. Zipf’s law for word frequencies, for example, can also be observed in the whistles of bottlenose dolphins. A criticism of Zipf’s law in the Chomskyan tradition holds that it just as well applies to random typing and rolling the dice, but Ferrer-i-Cancho showed that it is simply not the case by plotting the actual distribution of random typing and rolling the dice which is actually quite different from the logarithmic distribution of Zipf’s law if you look at it in any detail. The law that more frequent words are shorter can also be found in Chickadee calls, Formosan macaques and Common marmosets. There is some controversy whether this law really holds for all of these species, especially common marmosets, but Ferrer-i-Cancho presented a reanalysis of criticism in which he showed that what there are no “true exceptions” to the law. He proposes an information theoretic explanation for these kinds of behavioural universals where communicative solutions converge on a local optimum of differing communicative demands. He also proposes that considerations like this should lead us to change our perspective and concepts of universals quite radically, and that instead of looking only for linguistic universals we should also look for universals of communicative behavior and universal principles beyond human language such as cognitive effort minimization and mean code length minimization.

Returning to birds, Johan J. Bolhius picked the issue of similarities and differences up again and showed that there is in fact a staggering amount of similarities between birds and humans. For example, songbirds also learn their songs from a tutor (most often their father) and make almost perfect copies of their songs. As Hauser, Chomsky, Fitch 2002 have already pointed out, this signal copying seems not to be present in apes and monkeys. But the similarities go even further than that: Songbirds “babble” before they can sing properly (a period called ‘subsong’) and they also have a sensitive period for learning. And there are not only behavioural, but also neural similarities. In fact, songbirds seem to have a neural organization, broadly similar to the human separation between Broca’s area (mostly concerned with production, although this simple view of course is not the whole story, as James, for example, has shown) and Wernicke’s area (mostly concerned with understanding). So there seem to be regions that are exclusively activated when animals hears songs (kinda Wernicke-Type region) and regions with neuronal activation when animals sing, something which is called the ‘song system. Interestingly, this activation is also related to how much the animal has learned about that particular song it is hearing, so the better it knows the song the more activation is there. This means that this regions might be related to song memory. In lesion studies, where these regions involved in listening to a known song were damaged, recognition of the songs were indeed impaired but not wholly wiped out. Song production, on the other hand was completely unimpaired, mirroring the results from patients with lesions to either Broca’s or Wernicke’s areas. Zebra finches also show some degree of lateralization in that there is stronger activation in the left hemisphere when they hear the song they know, but not when the song they hear is unfamiliar. Although FOXP2 is not a “language gene”, which can’t be stressed enough, it is interesting that songbirds in which the bird-FOXP2-gene was “knocked out” show incomplete learning of the tutor songs.

Overall, Bolhuis concludes that what we can learn from looking at birdsong is that there are three significant factors evolved in the evolution of language:

Homology in the neural and genetic mechanisms due to our shared evolutionary past with birds.

Convergences or parallel evolution of auditory-vocal learning

And last specialisations, specifically human language syntax, which as Bolhuis argued in a paper with Bob Berwick and Kazuo Okanoya is still vastly different in complexity and hierarchical embedding from everything in songbird vocal behavior.

This focus on syntactic ability stems of course from a generativist perspective on these issues, and future research, especially from new and up-and-coming linguistic schools like Cognitive Linguistics and Construction Grammar (cf. Hurford 2012) is sure to bring more light into the matter of how exactly human language works, what kinds of elements and constructions it is made of, and how these compare to what is found in animals, and whether there really a single unitary thing like the fabled “syntactic ability” of humans (cf. e.g.work by Ewa Dabrowska)