In a series of posts, I’ve been discussing constraints on the evolution of colour terms. Here, I discuss the role of drift and also argue that universal patterns are not necessarily good evidence for innate constraints. For the full dissertation and references, go here.

Drift

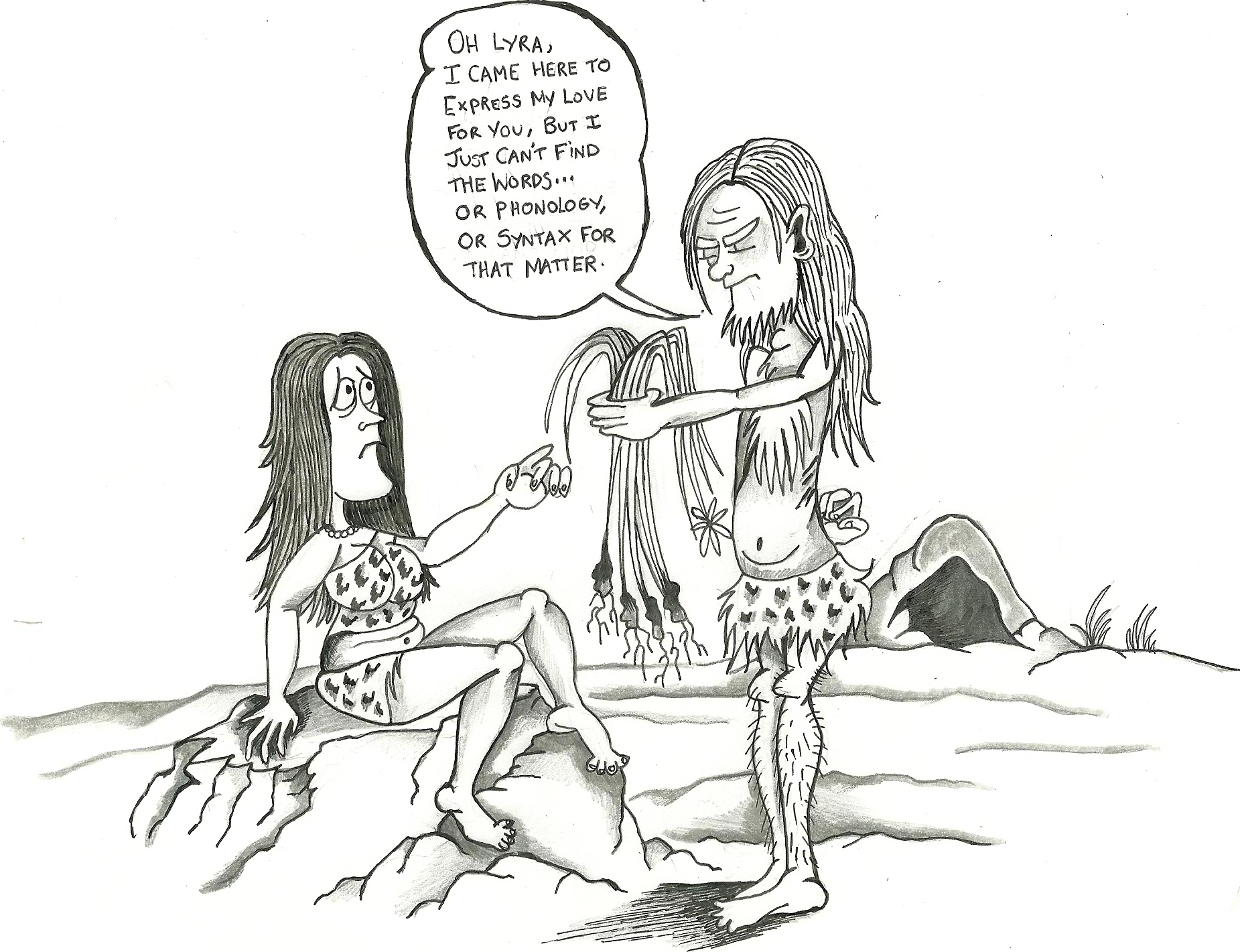

An important point which has not been highlighted in the literature is the drift introduced by cultural transmission. Perceptual systems are noisy, and change over lifetimes. Therefore, systems of categorising these perceptions may drift over time. However, if concepts are shared, this drift is influenced by more than one system. This may cause a different kind of drift from a stand-alone system for self-thought. Communication has an additional semantic bottleneck which self-though does not have. Using language for self thought, if you don’t know a label, you can make one up.

However, for communication, this won’t work. For example, in models of cultural transmission (e.g., Steels & Belpaeme, 2005) agents do create new labels but, importantly, accept the speaker’s label when available. That is, communicative systems are more flexible than systems for self-thought (communicators must be more willing to change their minds), and so are more subject to drift. The drift allows the system to move around the possible space of coding efficiency and object categorisation efficiency. Peaks in these landscapes will attract the drift, hence environmental and perceptual constraints being projected into language.

Although systems of colour categorisation for self-thought may be more efficient if they were constrained by the environment, shared cultural systems are more likely to reflect constraints in the environment because they are more flexible. That is, perceptual constraints have projected themselves into language because of a communicative pressure, rather than a perceptual or environmental pressure.

I suggest that this drift, together with an ability for categories to warp perceptual spaces, would mean that individuals converge on a shared perceptual system. If comprehension involves the activation of perceptual representations, then communication involves individuals reaching similar perceptual representations or, in a perfect world, activation of the same neural substrates. Therefore, a population with a shared perceptual system would be able to communicate much more effectively. In this sense, Embodied systems improve communicative success, whereas the same effect is not necessarily true of Symbolist systems. Furthermore, this drift means that populations can still converge on similar solutions, without having to assume that Universal biases are the main driving force. It has been argued that the similarities in colour categorisation between cultures contradicts Relativism, which would predict a large variation in colour categorisation between cultures (e.g., Belpaeme & Bleys, 2005). I argue that this inference is not necessarily valid.

Summary

This series of posts has shown that a wide range of factors constrain the categorisation of colour, including the physiology of perception, the environment and cultural transmission. Why is there evidence for Colour Terms being adapted to so many domains?

This study considered the idea that categorisation acquired by individuals can feed back into perception and itself become a constraint both on the development of categorisation, the environment and genetic inheritance. In this sense, the feedback from categorisation allows Niche Construction dynamics to apply to linguistic categorisations. It was argued that this dynamic fits with the Cultural implication of an Embodied account of language comprehension. That is, this study has concluded, similarly to Kirby et al. (2007), that universal patterns across populations do not necessarily imply strong innate biases. This was done by arguing that Cultural, Embodied systems tend to drift towards better representations of the real world, which involves better coherence with perceptual and environmental constraints, creating cross-cultural patterns. Furthermore, an Embodied approach to cultural dynamics incorporating a mechanism for perceptual warping predicts that the perceptual spaces of individuals can be synchronised through language to achieve better communication.

Steels, L., & Belpaeme, T. (2005). Coordinating perceptually grounded categories through language: A case study for colour Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28 (04) DOI: 10.1017/S0140525X05000087

Belpaeme, T. (2005). Explaining Universal Color Categories Through a Constrained Acquisition Process Adaptive Behavior, 13 (4), 293-310 DOI: 10.1177/105971230501300404

Kirby, S., Dowman, M., & Griffiths, T. (2007). Innateness and culture in the evolution of language Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104 (12), 5241-5245 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0608222104