A somewhat contentious debate among the behavioural sciences is currently underway concerning Mayr’s division of causal explanations in evolutionary theory. Here I’m going to give you a brief rundown of two papers in particular, before I chip in my two-cents about how other insights from the theoretical literature can inform this debate. It seems the discussion is just getting started with respect to cultural evolution, so it’d be interesting to hear other peoples’ comments from either camp.

Over the years, evolutionary theorists have tried to make logical divisions between the kinds of things we can ask about, with a view to making it clear what exactly scientific studies can tell us. A dominant paradigm dividing two levels of causation for biological features we see in the world is Mayr’s distinction between ultimate and proximate causes. Ultimate causation explains the proliferation of a trait in a population in terms of the evolutionary forces acting on that trait. For example, peahens that prefer peacocks with larger tails (an honest signal of fitness following the handicap principle) will have stronger or more successful offspring, and so this preference proliferates along with larger peacock tails. Proximate causation uses immediate physiological and environmental factors to explain a particular peahen’s penchant for a large-tailed peacock in a mate choice trial, where the signal of the peacock’s large tail elevates the hormone levels in the peahen and copulatory behaviour ensues. Although the behaviour in both of these examples is the same, the levels of explanation are based on different sets of factors.

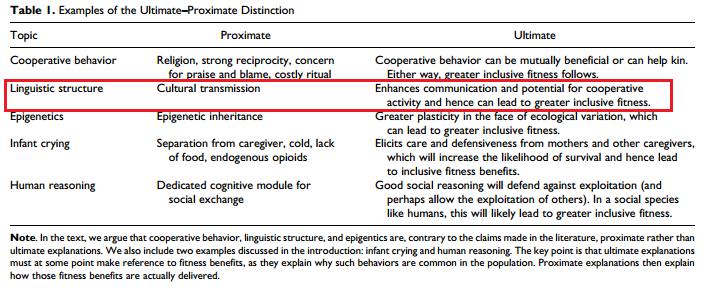

In Perspectives on Psychological Science last year, a paper by Scott-Phillips, Dickins and West voiced some concerns about these two levels of causation being conflated in the behavioural sciences. In particular, they addressed instances where proximate explanations of traits are being framed as ultimate ones. The paper points specifically to studies of the evolution of cooperation, transmitted culture and epigenetics to illustrate this. Regarding the evolution of cooperation, they point to an instance where ‘strong reciprocity’ (an individual’s propensity to reward cooperative norms and sanction violation of these norms) is purported to be an ultimate explanation of why humans cooperate, rather than a proximate mechanism that enables such cooperation.

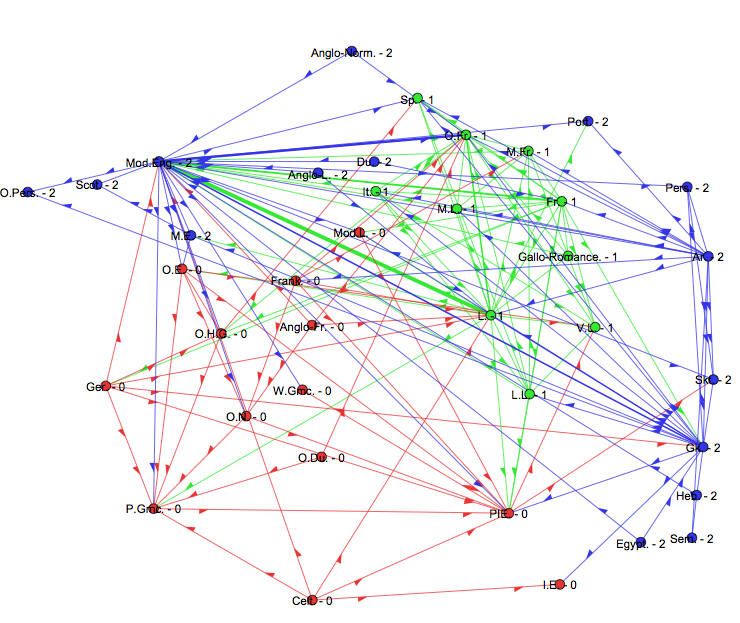

Among the examples was the feature of linguistic structure (see table 1 from paper above), where several studies pointed to the cultural transmission process as an ultimate explanation of linguistic structure. They suggest that cultural transmission constitutes a proximate process, because it gives the means by which linguistic structure is expressed – and this is how cultural transmission contributes to what the linguistic structure looks like. One analogy might be that the vibrating of my particular vocal cords is a proximate mechanism giving rise, in part, to how my voice sounds, rather than an ultimate explanation of why I vocalise. Since an ultimate account must suggest how a trait contributes to inclusive fitness in order to explain its prevalence in humans, they uncontroversially venture that the ultimate rationale for the ubiquity of linguistic structure is that it greater enables communication (and therefore increases inclusive fitness by enabling cooperative activity).

An opposing view was later published in Science by Laland, Sterelny, Odling-Smee et al., who suggest that the use of Mayr’s division of ultimate and proximate causation is not helpful to all evolutionary investigations, and even hampers progress. The grounds for rejecting Mayr’s paradigm seem to lie largely in what Laland et al. term “reciprocal causation”. That is, that “proximate mechanisms both shape and respond to selection, allowing developmental processes to feature in proximate and ultimate explanations”. After aligning proximate explanations with ontogeny and ultimate explanations with phylogeny, they suggest that what we may have called ultimate and proximate features are no longer sharply delineated, and that these reciprocal processes mean that the source of selection sometimes cannot be separated. They present an idea from the field of evolutionary-developmental biology that, if a developmental process makes some variant of a trait more likely to arise than others, then this proximate mechanism helps to construct an “evolutionary pathway”.

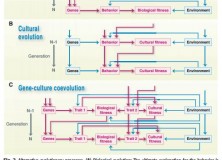

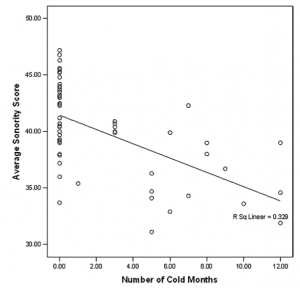

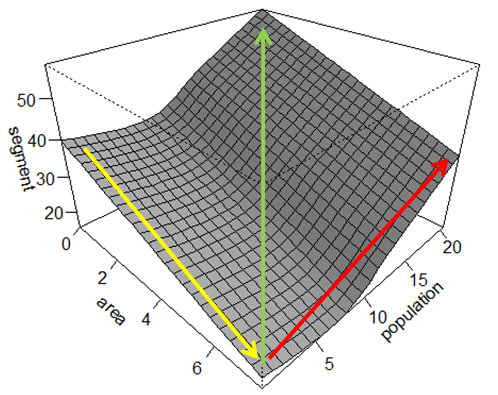

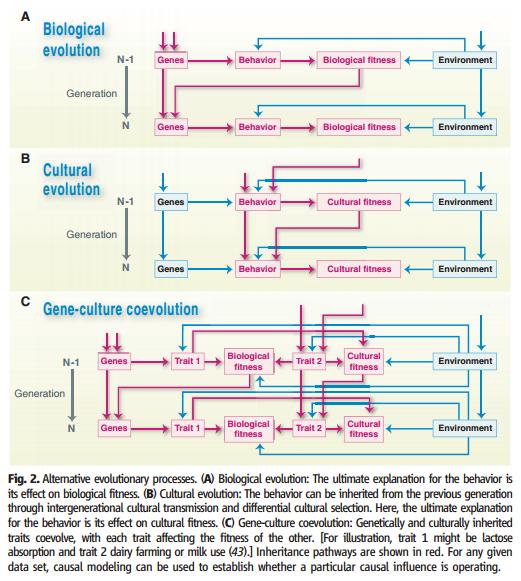

The paper also highlights developmental plasticity, and gene-environment interaction more broadly (see fig. 2 from paper, above), as a process where reciprocal causation offers an evolutionary explanation conceptually comparable to ultimate causation. Talking specifically on the topic of linguistic structure, they present the debate about whether specific design features of language are attributable to biological or cultural evolution. The paper points out that cultural evolution determines features of linguistic structure – for example, word order – and that the existing word order determines that of future speakers. Indeed, at the Edinburgh LEC we know that transmission by iterated inductive inference under general conditions can explain particular structures in languages. That cultural evolution determines the variation between languages, Laland et al. say, provides evidence that it is an evolutionary force comparable to natural selection (and, therefore, ultimate explanation).

What follows is a collection of my thoughts on the matter, which are (spoiler alert) largely in support of the Scott-Phillips et al. paper. I hope others more experienced in cultural evolution studies than I will contribute their perspective.

It seems to me that there are a few assumptions made in the Laland et al. paper that are not quite in line with how Mayr himself understood the paradigm. Perhaps much can be learned from this debate’s previous incarnation, when Richard C. Francis made similar arguments against the ultimate/proximate distinction in 1990. In his critique, he equated ultimate causation with phylogeny and proximate causation with ontogeny – an approach that was rebuked by Mayr in 1993, who made the point that “all physiological activities are proximately caused, but is a reflex an ontogenetic phenomenon?”. Mayr’s response is actually rather unhelpful in addressing the arguments fully, and this statement is particularly dense. But what he is getting at here is the idea that interaction with the environment that gives rise to adaptive behaviours (such as recoiling instantly from a hot stove) is itself subject to selection, and thus constitutes a proximate explanation of causation. Relatedly, he points out that most components of the phenotype are indeed the result of genetic contribution and interaction with the environment, which has been successfully explored in biology within the traditional theoretical paradigm.

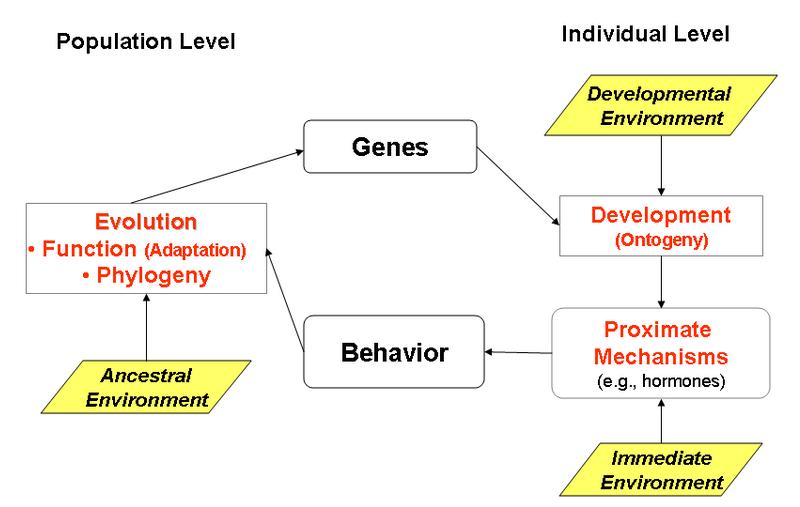

A perhaps more nuanced account of how we can divide the possible explanations of biological phenomena is offered by Tinbergen in his “four questions”, where ultimate explanations are further subdivided into Function (concerning the adaptive solution to a survival problem favoured by natural selection) and Phylogeny, which is a historical account of when the trait arose in the species, and importantly includes processes other than natural selection that give rise to variation – such as mutation, drift and the constraints imposed by pre-existing traits (see blind spot example below). Proximate explanations are further split into Mechanism (immediate physiological/environmental factors causal in how the trait operates in the individual) and Ontogeny (the way in which this trait develops over the lifetime of the individual). As a simple example, here is the paradigm applied to a trait like mammalian vision that I lifted from Wikipedia:

Ultimate

Function: To find food and avoid danger.

Phylogeny: The vertebrate eye initially developed with a blind spot, but the lack of adaptive intermediate forms prevented the loss of the blind spot.

Proximate

Causation: The lens of the eye focuses light on the retina

Ontogeny: Neurons need the stimulation of light to wire the eye to the brain within a critical period (as those awful studies of blindfolded kittens illustrated).

A schematic below, adapted from Tinbergen (1963) shows how these levels of causation may interact with one another, which appears to communicate something roughly comparable to the importance Laland et al. place on “reciprocal causation” in the formation of adaptive variants:

Applied to the debate outlined above, it would seem that there is no apparent reason that a process of gene-environment interaction – including the cultural environment – can’t itself be subject to selection, or that developmental plasticity itself is not an adaptation in need of an ultimate explanation. It has long been the case that behaviour is no longer understood as either “nature” or “nurture”, but gene-environment interaction, with varying levels of heredity. The “reciprocal causation” suggested in Laland et al.’s paper, is (as they point out) very common in nature; feedback loops are uncontroversial proximate processes in biology. That a proximate process may give rise to a dominant variant of a trait in a population does not explain why it is adaptive, and this points to another problem with the proposing the abandonment of Mayr’s paradigm: a logical division of levels of explanation doesn’t seem to be the sort of thing that can be rendered outdated by empirical evidence. Indeed, claims about the particulars of traits and processes (and languages) themselves are a matter for empirical data – but the theoretical issue about the level of explanation that data is useful for does not itself seem to be subject to empirical findings.

The finding that a proximate process such as cultural transmission gives rise to a trait that is prolific in a population is itself exciting and surprising, and even shows us that the pressure for making language easier to learn gives us adaptive languages to learn; however, it could be argued that it is this process that is adaptive, and that the reason why humans so heavily rely on this process is an ultimate explanation.

One way of resolving these two perspectives may be to place cultural processes that give rise to variation at the level of what Tinbergen labels Phylogenetic (one subset of ultimate) explanation, as it concerns processes which produce some heightened frequency of traits over a language’s history. An explanation at the level of Phylogeny still must make recourse to natural selection at some point, since variants that result from mutation or drift are retained because of their adaptive value (or an adaptive trade-off). This approach may be a problem for the current understanding, which holds that the features resulting from cultural processes are themselves adaptive and therefore comparable to what Tinbergen labels Function.

The problem with this is that calling particular structures of language ‘adaptive’ obscures what it is about Language that is actually being selected for. To flesh out what I mean, I think it’s useful to consult Millikan’s (1993) distinction between Direct Proper Function and Derived Proper Function (… bear with me, it’ll be worth it, honest). The Direct Proper Function of a given trait T can be thought of as a “reproduction” of an item that has performed the exact same adaptive function F, and T exists because of these historical performances of F. Sperber and Origgi (2000) use the illustrative example of the heart, where the human heart has a bunch of properties (it pumps blood, makes a thumping noise, etc), but only its ability to pump blood is its Direct Proper Function. This is because even a heart that doesn’t work right or makes irregular thumping noises or whatever, still has the ability to pump blood. Hearts that pump blood have been “reproduced through organisms that, thanks in part to their owning a heart pumping blood, have had descendents similarly endowed with blood-pumping hearts”.

The Derived Proper Function, however, refers to a trait T that is the result of some device that, in some environment, has a Proper Function F. In that given environment, F is usually achieved by the production of something like T. If I unpack this idea and apply it to language, we can understand it as the acquisiton and production of a device that, in this environment, leads to, say, a particular SVO language, T. The Proper Function of adaptive communication is performed by T in this case, but could also be performed by any number of SOV, VSO, etc Ts in other cases. In other words, the Proper Function of this language is not the word order itself, but communication. The word order is the realisation of this device that is reproduced because of the performance of T in a particular environment, but does not necessarily lead to T in the next incarnation of that device (i.e. My child, if born and raised in Japan, will speak Japanese). We see, then, that a proximate process resulting in what a particular language spoken by a given population looks like does not necessarily speak to the evolutionary function. In other words, it is the device that allows the performance of Language that is adaptive, not the individual language itself.

One question being asked in the study of cultural transmission is why a particular language looks like it does, while we also know that there are 6000 different versions that perform the same (ultimate) function. I would even argue that asking how proximate processes shape languages is actually the most exciting and interesting avenue of inquiry precisely because it’s so blindingly obvious what the adaptive function of language is. But perhaps the value in this endeavour is somewhat neglected, in part, because of the same impression that Francis (1990) had: “the attitude, implicit in the term ultimate cause, [is] that these functional analyses are somehow superordinate to those involving proximate causes” which would be a shame. It seems to me that the coarse grain of ultimate vs proximate perhaps doesn’t do enough to help complex proximate study to position itself in the wider theoretical framework, and the best way to proceed from this might be to couch explanation in terms of Function, Phylogeny, Ontogeny and Mechanism. I think more fine-grained terminology grants us more explanatory power, in this case.

A final question in this debate that came up too many times during discussions with the LEC is: what does keeping the traditional paradigm “buy us”? Well, the first answer to this is consilience with one of the most successful and robust theories in science. The same sentiment has been communicated by Pinker and Bloom (1990), who said: “If current theory of language is truly incompatible with the neo-Darwinian theory of evolution, one could hardly blame someone for concluding that it is not the theory of evolution that must be questioned, but the theory of language”. Part of the reason this debate may have arisen is that studies of cultural evolution have used evolutionary theory as an incredibly fruitful way of analysing cultural processes, but additional acknowledgement about how cultural adaptation is different to biological adaptation may be necessary. This difference is an aspect of Laland’s paper (shown in Fig 2) that I think is important, as it’s part of the reason that more nuanced frameworks for cultural evolution are now needed. Without this widespread acknowledgement, cultural evolution may be considered an extension of biological evolutionary theory instead of a successfully applied metaphor. It seems to me that the side of this debate one falls on is well predicted by whether one subscribes to the former interpretation of cultural evolution or the latter.

Knowing which level of explanation current work pertains to is a valuable part of evolutionary exploration, and abandoning this in favour of an approach where proximate processes are explanatory ends to themselves may mean the exploration of Function and Phylogeny may suffer. That said, it is telling, I think, that even in seeking to abandon the proximate/ultimate distinction, we must still exploit this existing terminology in order to explain such a position. That natural selection has explained countless adaptations in all living things is certainly not trivial, and to reject the theory giving rise to ultimate explanations as they’re currently defined is to reject this fundamental aspect of evolutionary theory. The big problem seems to be that we’re coming to understand proximate processes as so elaborate and complex, that a more nuanced framework is needed to deal with the dynamics of those processes. I reckon, however, that such a framework can be developed within the traditional paradigms of evolutionary theory.

References

Francis, R.C. (1990) – “Causes, Proximate and Ultimate” Biology and Philosophy 5(4) 401-415.

Laland, K., Sterelny, K., Odling-Smee, J., Hoppitt, W. & Uller, T. (2011) – “Cause and Effect in Biology Revisited: Is Mayr’s Proximate-Ultimate Distinction Still Useful?” Science 334, 1512-1516.

Mayr, E. (1993) – “Proximate and Ultimate Causations” Biology and Philosophy 8: 93-94.

Millikan, R. (1993) – White Queen Psychology and Other Essays for Alice, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Pinker, S. & Bloom, P. (1990) – “Natural language and natural selection” Behaviour and Brain Sciences 13, 707-784.

Scott-Phillips, T. Dickins, T. & West, S. (2011) – “Evolutionary Theory and the Ultimate-Proximate Distinction in the Human Behavioural Sciences” Perspectives on Psychological Science 6(1): 38-47.

Sperber, D. & Origgi, G. (2000) – “Evolution, communication and the proper function of language” In P. Carruthers and A. Chamberlain (Eds.) Evolution and the Human Mind: Language, Modularity and Social Cognition (pp.140-169) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tinbergen, N. (1963) “On Aims and Methods in Ethology,” Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie, 20: 410–433.