There is a “Skeptics In The Pub” event in Glasgow on March 4th, where Dr Thom Scott-Phillips will be discussing the perceptions and misconceptions of evolutionary psychology, in light of the public backlash against it that seems to be increasing all the time. This kind of public engagement is very sorely needed if we are to combat the rampant misinformation that crops up in both academic and non-academic communities. Among the criticisms being addressed at the event are the claims that evolutionary psychology is sexist, racist, or otherwise politically problematic. This is an important discussion.

From what I see around the feminist blogosphere, evolutionary psychology has a bad rap. Some recent examples I’ve come across include comments such as: “This new junk science named “evolutionary psychology” is the last variant of the male supremacy bible, following Freud’s mythology” and “[the way this article approaches the problem] is a bad idea [because] It smacks of evo psyche”. Even more liberal feminist blogs such as The F Word UK toe a similar line: Josephine Tsui seems to be on a personal mission against Evolutionary Psychology, armed with such ludicrous arguments as “You cannot replicate Evolutionary Psychology therefore it fails the methodologies of science” which display both an immature line of thinking and a fundamental misunderstanding of the theoretical motivations and methodologies entailed. Needless to say I’ve never seen this criticism leveraged against Evolutionary Biology, despite it being applicable to both.

Evolutionary psychology has a sound theoretical basis; it has been well established that natural selection is a means by which complex life and complex behaviour occurs. This tends to worry political movements like feminism, which has its roots in social constructionism. Such worry is unfounded; there is certainly a role for social constructionism within an evolutionary account of human behaviour. Put broadly, our plastic brains depend on complex social learning and pedagogy, which is an established cornerstone of human success. This ability to respond to (and be shaped by) the cultural environment has itself been selected for in humans, and can account for all manner of behaviours from language to mating preferences. Keep reading for a demonstration of how evolutionary psychology can in fact lend itself very well to the goal of engineering of social change.

So, on one side of the sexually selective understanding coin is a worried feminist movement, who risk losing a good grasp of evolutionary psychology by dismissing it entirely. On the other side, are the misogynist (mis)interpretations that have inspired this trepidation in the first place. That evolutionary psychology is abused and misinterpreted by misogynists and racists (and let’s be real here, this has happened a lot) is the problem, and it’s a serious one with real political consequences. Just this year, Steve Moxon submitted evidence to parliament (and was subsequently invited to speak) against the development of measures to encourage women in the workplace. Evolutionary psychology formed the backbone of his case, and he is not alone. Only an informed public can approach these claims with adequate discernment, so it is important that we address how some claims are morally wrong and incorrect. But it is also as important to discuss why they do not represent anything inherent about evolutionary psychology as a discipline.

We can illustrate the first way that evolutionary psychology can be wrong by using the problem of eugenics. Eugenics is theoretically sound, in as much as we know that we can selectively breed to a criteria and expect a predictable result; we’ve been doing it with dogs for 10 thousand years. This is also morally wrong and should not be attempted in humans. Just because eugenics is morally reprehensible, however, doesn’t mean we say the principles of artificial (or natural) selection aren’t true. Nor should this be the case for evolutionary psychology as a field; that it has been misapplied/misinterpreted within our social context (or just says something that we don’t like) simply does not speak to how scientifically correct it is. Another way that the interpretation of these studies can be grossly wrong is the Naturalistic Fallacy; the idea that if something is natural, it is inherently good or should be normative. This is obviously untrue; my human body is adapted to long-distance running, but I reject outright the idea that this is something I ought to engage in.

While citing the naturalistic fallacy is a good answer to most any claim about innate human proclivities, I think it’s also necessary to refute specific claims on their own grounds where possible. The final way for evolutionary psychology to be wrong is simply that rationalisation isn’t science, and instances where it is being passed off as such can be exposed for what they are. To illustrate, we generally do not dismiss the entirety of modern medicine as false because of the historical mistreatment of pregnant women in childbirth by doctors. Here, we can see that those occurrences are indeed morally wrong. However, it’s also the case that those instances are bad medicine by medicine’s own standards. Similarly, instances of bad science in evolutionary psychology, where latent misogyny and racism rears its head, can be refuted on their own grounds. This can and should be done without blithely dismissing the entire field.

It is a disaster that large factions of social justice movements are on the verge of outright anti-intellectualism when it comes to evolutionary psychology. Preserving ignorance about the field with out-of-hand dismissal neglects the potential for this tool to contribute to worthwhile political goals. We don’t have to stop at simply refuting the harmful instances of bad evolutionary study; there is also a positive agenda to be highlighted here. In the spirit of this, I’d like to share a preview of some work I’ve been hobbying with Justin Quillinan, inspired by a recent paper called “Asia’s Missing Women: A Problem in Applied Evolutionary Psychology?”. The paper aims to explore sex-preferential parental investment, which is a prolific problem in parts of Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, where the population’s sex-ratios are heavily male skewed as a result. It is already well documented that women suffer like this, so what can an evolutionary analysis can bring to the table? The problem, as presented in the paper, is this:

Asia’s missing women are, in economic terms, an aggregate outcome of millions of parenting decisions. The individual drivers behind those decisions emerge from interactions between our evolved parenting preferences and social and economic circumstances.

How do we untangle this seemingly nebulous problem? How do we determine why many self-perceived individuals act in such a similar way that the net result is the literal eradication of the female class? The approach of the paper seems to be largely influenced by economics, which is fairly central to a lot of evolutionary work. Game theory can be paraphrased as something like “given that the rules of the game are (x, y, z), which strategy should I employ to reap the most advantageous outcome?”. The most successful strategy is the one that is most likely to survive in the population, and hence it is the one we most expect to find. If we treat the problem of parents favouring boys over girls as a solution to the problem of parents’ circumstances, the question then becomes “what are the parameters that make this survival strategy worth employing such that it is so common?”

By comparing the commonalities in cultures that have this problem, Brooks identifies some ecomonic and social factors that may reward preferential parental investment. This is important: it means that campaigners for change don’t have to simply say the reason that girls are selectively aborted or neglected starts and ends with “girls are undervalued in these cultures”. Despite how true that is, it is also true of many cultures who do not have skewed sex ratios, and doesn’t really point to any concrete way of tackling the problem. If we can identify the driving factors that make parents behave this way with an evolutionary analysis, it means we can target specific structures with a specific end goal in mind.

In an interesting and wide-ranging investigation, the paper compares skewed parental investment occurence in non-human animals with the social and historical particulars that have led to this behaviour in disparate human populations. In doing so, Brooks proposes that male sex-biased populations are the systematic result of a population’s patrilineage, patrilocal kinship systems, and the dowry system. It was my hunch that the sex-biased population ratio could be reducible to patrilocality alone; that is, the system whereby women leave their blood relatives in order to live with (and care for) their husband’s family when they marry. Let us assume that the number of blood relatives in your family is a proxy measure of fitness. In a patrilocal social order, it is necessarily the case that having a son is more advantageous than having a daughter – precisely because daughters will always leave. Let us now also factor in the effects of infanticide and abortion; the option to neglect/kill your male/female offspring according to whether or not the most successful families you know had a boy or girl, will lead to the preferential elimination of females.

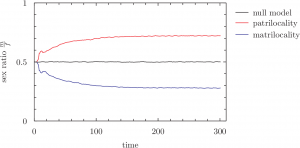

So we’ve implemented a model (source code available here) demonstrating exactly this:

We start with a population of agents separated into a number of families of a single breeding pair each single individuals. At each time-step, the following events occur:

1. Reproduction: fertile breeding pairs of agents have a new agent ‘child’ of random sex. A fertile pair is one that does not have an unmarried child that is younger than the age of maturity.

1.2. Abortion: Now, the pair can choose to either keep or to abort their new agent. To make this decision, they choose a random family, with larger families having a proportionally higher probability of being chosen. If the sex ratio of that family is a mismatch to the child they have just had, they will abort the child. Otherwise, they will keep it. (ETA: the abortion decision is based on the sex ratio of all the offspring of the chosen family).

2. Marriage: Every single, mature agent attempts to pair with a random, opposite sex partner from a different family, to form a breeding pair. In patrilocality, the female leaves her family and is appended to her husband-agent’s family to form a breeding pair. (In the matrilocality sanity check, the situation is vice versa and male agents join their wives’ families).

3. Death: Agents above a certain age are removed from the population. If a family no longer has any members, we generate a new breeding pair individual so that the population doesn’t die out.

The first null model was as above, with the omission of step 1.2. We later implemented one that is as above, but minus patrilocal marriage (ie, married agents simply form a new family pair) because this is a better comparison.

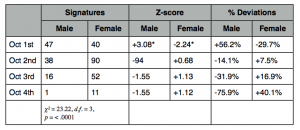

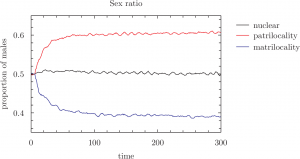

At each time-step, we measure the sex ratio of the population. This is what happens (wordpress is terrible, click for a clearer image):

The sex-ratio of the population is skewed in the direction of the sex that determines family locality – that is to say, patrilocality alone systematically results in the preferential abortion of female offspring, and a higher ratio of males in the population to females. This model will hopefully lend itself to some further work exploring the role of the dowry in maintaining the system by offsetting the costs of giving away offspring, preferential marrying, and how a shift toward “nuclear” family arrangements may have lifted the cost-benefit situations disadvantaging females (and thus making dowry systems redundant).

UPDATE (09/02/12): Here is the data using an amended null model:

The ‘bump’ at around time-step 20 in the first graph noticed by Sean (see comments section) doesn’t appear here; this was an artefact of seeding with identical pairs that breed and die at the same time. Seeding with individuals has smoothed out that curve; staggering the ages of agents would likely smooth it out further. The extra noise in this model means that the skew is less pronounced than before; note the Y axis is zoomed in to ~0.3 – 0.7. The null model here is of the null hypothesis; abortion still happens, the only difference is that instead of a married agent appending to their spouse’s family, the married couple form a new family pair (ie. no matri/patrilocality). This means that any single given population’s sex ratio is susceptible to drift; early, small aberrations toward male or female will become magnified over time. This is, however, equally likely to happen for either male or female, and so the average of 1000 populations shown here is stable at 0.5.

Further implications:

An important additional observation in Brooks’ paper is an examination of the wider social consequences of this particular set of circumstances. The paper names elevated levels of “men competing furiously for wealth and status” as well as “risk-taking, violence, gambling, alcohol and drug abuse, kidnapping and trafficking of women, and the use and abuse of prostitutes” as consequences of surplus males in the population. The implication is that, by this model, these large societal problems can be addressed at least in part by balancing parental investment in children of both sexes, which would be remarkable.

At first blush, the idea that violence results from a surplus of men who don’t have a good enough chance at mating with women has some worrying and problematic implications. It is, nevertheless, intuitively true within a culture of male entitlement, which is something that feminists have long observed – that male violence is the result (and the maintenance) of a patriarchal social order. Since patrilineage, and patrilocality in family structure specifically, are identified as the preconditions for preferential parental investment in males, the eradication of this social order is a necessary step in redressing the sex-ratio balance. The end of patrilineal traditions and patrilocality are also a step toward dismantling a culture of male entitlement more broadly. As a direct consequence, then, this strategy dismantles the structures supporting male entitlement itself at the same time as addressing the skewed sex ratio, and does not simply consist of “giving the men more women to stop them fighting”.

It seems to me that a feminist account that names a culture of male entitlement as the cause for violent female oppression, and an evolutionary account that names structural entitlement systems as the cause for the mass devaluation/infanticide of female offspring are very much on the same page. This approach also very clearly illustrates the compatibility between evolutionary analysis and the socio-economic determinism that is fundamental to radical political thought, precisely by demonstrating how population-wide behaviour can directly result from external economic and social parameters, rather than some innately predisposed condition. We hope that this is at least one small demonstration of how evolutionary psychology and social justice can be rather natural allies.