[This is a guest post by Stefan Hartmann]

“Chomsky still rocks!” This comment on Twitter refers to a recent paper in PNAS by David M. Gómez et al. entitled “Language Universals at Birth”. Indeed, the question Gómez et al. address is one of the most hotly debated questions in linguistics: Does children’s language learning draw on innate capacities that evolved specifically for linguistic purposes – or rather on domain-general skills and capabilities?

Lbifs, Blifs, and Brains

Gómez and his colleagues investigate these questions by studying how children respond to different syllable structures:

It is well known that across languages, certain structures are preferred to others. For example, syllables like blif are preferred to syllables like bdif and lbif. But whether such regularities reflect strictly historical processes, production pressures, or universal linguistic principles is a matter of much debate. To address this question, we examined whether some precursors of these preferences are already present early in life. The brain responses of newborns show that, despite having little to no linguistic experience, they reacted to syllables like blif, bdif, and lbif in a manner consistent with adults’ patterns of preferences. We conjecture that this early, possibly universal, bias helps shaping language acquisition.

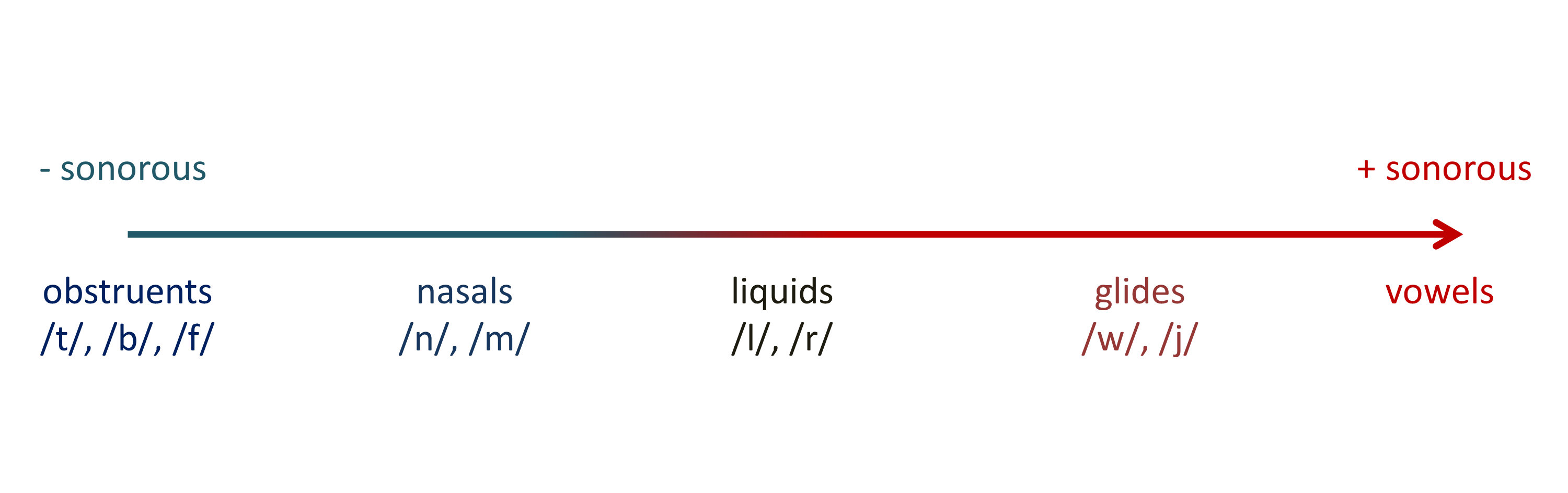

More specifically, they assume a restriction on syllable structure known as the Sonority Sequencing Principle (SSP), which has been proposed as “a putatively universal constraint” (p. 5837). According to this principle, “syllables maximize the sonority distance from their margins to their nucleus”. For example, in /blif/, /b/ is less sonorous than /l/, which is in turn less sonorous than the vowel /i/, which constitues the syllable’s nucleus. In /lbif/, by contrast, there is a sonority fall, which is why this syllable is extremely ill-formed according to the SSP.

In a first experiment, Gómez et al. investigated “whether the brains of newborns react differentially to syllables that are well- or extremely ill-formed, as defined by the SSP” (p. 5838). They had 24 newborns listen to /blif/- and /lbif/-type syllables while measuring the infant’s brain activities. In the left temporal and right frontoparietal brain areas, “well-formed syllables elicited lower oxyhemoglobin concentrations than ill-formed syllables.” In a second experiment, they presented another group of 24 newborns with syllables either exhibiting a sonority rise (/blif/) or two consonants of the same sonority (e.g. /bdif/) in their onset. The latter option is dispreferred across languages, and previous behavioral experiments with adult speakers have also shown a strong preference for the former pattern. “Results revealed that oxyhemoglobin concentrations elicited by well-formed syllables are significantly lower than concentrations elicited by plateaus in the left temporal cortex” (p. 5839). However, in contrast to the first experiment, there is no significant effect in the right frontoparietal region, “which has been linked to the processing of suprasegmental properties of speech” (p. 5838).

In a follow-up experiment, Gómez et al. investigated the role of the position of the CC-patterns within the word: Do infants react differently to /lbif/ than to, say, /olbif/? Indeed, they do: “Because the sonority fall now spans across two syllables (ol.bif), rather than a syllable onset (e.g., lbif), such words should be perfectly well-formed. In line with this prediction, our results show that newborns’ brain responses to disyllables like oblif and olbif do not differ.”

How much linguistic experience do newborns have?

Taken together, these results indicate that newborn infants are already sensitive for syllabification (as the follow-up experiment suggests) as well as for certain preferences in syllable structure. This leads Gómez et al. to the conclusion “that humans possess early, experience-independent linguistic biases concerning syllable structure that shape language perception and acquisition” (p. 5840). This conjecture, however, is a very bold one. First of all, seeing these preferences as experience-independent presupposes the assumption that newborn infants do not have linguistic experience at all. However, there is evidence that “babies’ language learning starts from the womb”. In their classic 1986 paper, Anthony DeCasper and Melanie Spence showed that “third-trimester fetuses experience their mothers’ speech sounds and that prenatal auditory experience can influence postnatal auditory preferences.” Pregnant women were instructed to read aloud a story to their unborn children when they felt that the fetus was awake. In the postnatal phase, the infants’ reactions to the same or a different story read by their mother’s or another woman’s voice were studied by monitoring the newborns’ sucking behavior. Apart from the “experienced” infants who had been read the story, a group of “untrained” newborns were used as control subjects. They found that for experienced subjects, the target story was more reinforcing than a novel story, no matter if it was recited by their mother’s or a different voice. For the control subjects, by contrast, no difference between the stories could be found. “The only experimental variable that can systematically account for these findings is whether the infants’ mothers had recited the target story while pregnant” (DeCasper & Spence 1986: 143).