When asked to name a linguistically diverse place, I would have said Papua New Guinea, and if asked to name a stereotypically monolingual country, I would have named the USA. However, this recent report from the New York Times suggests that, due to its large immigrant population, New York harbours more endangered languages than anywhere else on Earth (tipped off from Edinburgh University’s Lang Soc Blog). From a field linguists’ point of view this may make discovery of and access to minority languages much easier (although may mean the end of exotic holidays). From a cultural evolution point of view, a more global community may mean a radically different kind of competition between languages. Nice video below:

Tag: evolution

Fun language evolution experiment!

Do a fun language experiment!*

You can take part in a pilot experiment about language learning: It takes about 8 minutes (and is NOT an iterated learning experiment, although it looks a bit like one). I’ll release the results (and the hypothesis) right here on Replicated Typo.

* may not be loads of fun.

Language Evolves in R, not Python: An apology

One of the risks of blogging is that you can fire off ideas into the public domain while you’re still excited about them and haven’t really tested them all that well. Last month I blogged about a random walk model of linguistic complexity (the current post won’t make much sense unless you’ve read the original). Essentially, it was trying to find a baseline for the expected correlation between a population’s size and a measure of linguistic complexity. It assumed that the rate of change in the linguistic measure was linked to population size. Somewhat surprisingly, correlations between the two measures (similar to the kind described in Lupyan & Dale, 2010) emerged, despite there being no directional link.

However, these observations were made on the basis of a relatively small sample size. In order to discover why the model was behaving like this, I needed to run a lot more tests. The model was running slowly in python, so I transliterated it to R. When I did, the results were very different: In the first model an inverse relationship between the population size and the rate of change of linguistic complexity yielded a negative correlation between population size and linguistic complexity (perhaps explaining results such as Lupyan & Dale’s). However in the R model this did not occur. In fact, significant correlations only appeared 5% of the time, with that 5% being split exactly between positive and negative correlations. That is, the baseline model has a standard confidence interval, not the much stricter one I had suggested in the last post.

Why was this happening? In short: Rounding errors and small sample sizes.

I checked the Python code, but couldn’t find a bug, so the correlations really were appearing, and really were favouring a negative correlation. Here’s my best explanation: First, the sample of runs was too low to capture the proper distribution. However, strong correlations were appearing. This could be because although the linguistic complexity measure started out pretty randomly distributed, the individual communities were synchronising at the maximum and minimum of the range as they bumped up against it. This caused temporary clusters in the low ranges where the linguistic complexity was changing rapidly (and therefore more likely to synchronise), creating tied ranks in the corners. In addition to this, the Python script I was using had a lower bit depth for its numbers than R, so was more prone to rounding errors. I have to assume as well that my Python script somehow favoured numbers closer to 1 than to 0. It’s still not a very satisfactory explanation, but the conclusion remains that, as one would expect, affecting just the rate of change of linguistic complexity does not produce correlations.

Modelling evolutionary systems often runs into these kinds of problems: The search spaces are often intractable for some approaches. Also I am not, as a mere linguist, aware of some of the more advanced computational techniques. It’s one of the reasons that Evolutionary Linguistics requires a pluralist approach and tools from many different disciplines.

It’s embarrassing to have to correct previous statements, but I guess that’s what Science is about. In the blogging age ideas can get out before they’re fully tested and potentially affect other work. This has its advantages – good ideas can get out faster. But it also means that the reader must be more critical in order to catch poor ideas like the one I’m correcting here.

Sorry, Science.

Here’s a link to the R script (25 lines of code!).

Lupyan G, & Dale R (2010). Language structure is partly determined by social structure. PloS one, 5 (1) PMID: 20098492

Cultural Evolution and the Impending Singularity: The Movie

Here’s a video of a talk I gave at the Santa Fe Institute‘s Complex Systems Summer School (written with roboticist Andrew Tinka-check out him talking about his fleet of floating robots). The talk was a response to the “Evolution Challenge”:

- Has Biological Evolution come to an end?

- Is belief an emergent property?

- Will advanced computers use H. Sapiens as batteries?

I also blogged about a part of this talk here (why a mad scientist’s attempt at creating A.I. to make new scientific discoveries was doomed).

The talk was given a prise for best talk by the judging panel which included David Krakauer, Tom Carter and best-selling author Cormac McCarthy. At several points in the talk, I completely forget what I was supposed to say because the people filming the event asked me to set my screen up in a way so I couldn’t see my notes.

Sperl, M., Chang, A., Weber, N., & Hübler, A. (1999). Hebbian learning in the agglomeration of conducting particles Physical Review E, 59 (3), 3165-3168 DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevE.59.3165

Chater N, & Christiansen MH (2010). Language acquisition meets language evolution. Cognitive science, 34 (7), 1131-57 PMID: 21564247

Ay N, Flack J, & Krakauer DC (2007). Robustness and complexity co-constructed in multimodal signalling networks. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 362 (1479), 441-7 PMID: 17255020

Ackley, D.H., and Cannon, D.C.. “Pursue Robust Indefinite Scalability”. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth Workshop on Hot Topics in Operating Systems (HOTOS-XIII) (2011, May). Abstract, PDF.

Guttal V, & Couzin ID (2010). Social interactions, information use, and the evolution of collective migration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107 (37), 16172-7 PMID: 20713700

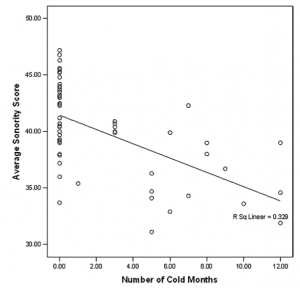

Sonority and Sex: Why smaller communities are louder

![]() Through this post on Sprogmuseet about Atkinson’s analysis of the out of Africa hypothesis, I found an article by Ember & Ember (2007) (who also quantified the link between colour lexicon size and distance from the equator, see my post here) on Sonority and climate. The article extends work by Fought et al. (2004) which finds that a language’s sonority is related to climate. Sonority is a measure of amplitude (loudness) as is greater for vowels than for consonants (for example, see here). Basically, the warmer the climate, the greater the sonority of the phoneme inventory of the population. The theory is that “people in warmer climates generally spend more time outdoors and communicate at a distance more often than people in colder climates”.

Through this post on Sprogmuseet about Atkinson’s analysis of the out of Africa hypothesis, I found an article by Ember & Ember (2007) (who also quantified the link between colour lexicon size and distance from the equator, see my post here) on Sonority and climate. The article extends work by Fought et al. (2004) which finds that a language’s sonority is related to climate. Sonority is a measure of amplitude (loudness) as is greater for vowels than for consonants (for example, see here). Basically, the warmer the climate, the greater the sonority of the phoneme inventory of the population. The theory is that “people in warmer climates generally spend more time outdoors and communicate at a distance more often than people in colder climates”.

Continue reading “Sonority and Sex: Why smaller communities are louder”

Digital Humanities Sandbox Goes to the Congo

Or, Speculations in Computational Evolutionary Psychology

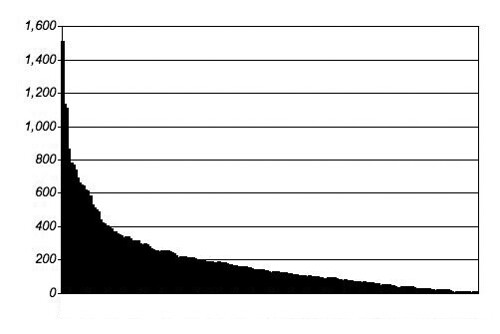

Note: This version of the post has been revised from an earlier version in which I suggested that the distribution in the first chart followed a power law. Cosma Shalizi checked it for me and it’s not a power law distribution. It’s an exponential distribution.

So, I’ve been exploring Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. In the last two posts I’ve examined one paragraph in the text, the so-called nexus. It’s the longest paragraph in the text, it’s structurally central, and it covers a lot of semantic territory.

OK, but what about the other paragraphs.

What about them?

Aren’t you going to look at them?

Well, yeah, but I sure don’t have time to troll through them like I did the nexus. I mean, that post stretched from here to Sunday.

I get your point. Why don’t you do the Moretti thing?

Moretti thing?

You know, distant reading.

Distant reading? You mean count something? Count what?

How about paragraph length?

What’ll that get me?

I don’t know. Just do it. I mean, you already know that the nexus is the longest paragraph in the text. There must be something going on with that. Mess around and see if something turns up.

* * * * *

I used the MSWord word-count tool to count the words in every paragraph in the text. All 198 of them. One at a time. Real tedious stuff. Then I loaded the results into a spreadsheet and created a bar chart showing paragraph length from longest to shortest:

Continue reading “Digital Humanities Sandbox Goes to the Congo”

Continue reading “Digital Humanities Sandbox Goes to the Congo”

Cultural Evolution and the Impending Singularity

Prof. Alfred Hubler is an actual mad professor who is a danger to life as we know it. In a talk this evening he went from ball bearings in castor oil to hyper-advanced machine intelligence and from some bits of string to the boundary conditions of the universe. Hubler suggests that he is building a hyper-intelligent computer. However, will hyper-intelligent machines actually give us a better scientific understanding of the universe, or will they just spend their time playing Tetris?

Let him take you on a journey…

Continue reading “Cultural Evolution and the Impending Singularity”

Academic Networking

Who are the movers and shakers in your field? You can use social network theory on your bibliographies to find out:

Today I learned about some studies looking at social networks constructed from bibliographic data (from Mark Newman, see Newman 2001 or Said et al. 2008) . Nodes on a graph represent authors and edges are added if those authors have co-authored a paper.

I scripted a little tool to construct such a graph from bibtex files – the bibliographic data files used with latex. The Language Evolution and Computation Bibliography – a list of the most relevant papers in the field – is available in bibtex format.

You can look at the program using the online Academic Networking application that I scripted today, or upload your own bibtex file to find out who the movers and shakers are in your field. Soon, I hope to add an automatic graph-visualisation, too.

Laryngeal Air Sacs

So, I got a request from a friend of mine to make an abstract on the fly for a poster for Friday. I stayed up until 3am and banged this out. Tonight, I hope to write the poster justifying it into being. A lot of the work here builds on Bart de Boer’s work, with which I am pretty familiar, but much of it also started with a wonderful series of posts over on Tetrapod Zoology. Rather than describe air sacs here, I’m just going to link to that – I highly suggest the series!

Here’s the abstract I wrote up, once you’ve read that article on air sacs in primates. Any feedback would be greatly appreciated – I’ll try to make a follow-up post with the information that I gather tonight and tomorrow morning on the poster, as well.

Re-dating the loss of laryngeal air sacs in hominins

Laryngeal air sacs are a product of convergent evolution in many different species of primates, cervids, bats, and other mammals. In the case of Homo sapiens, their presence has been lost. This has been argued to have happened before Homo heidelbergensis, due to a loss of the bulla in the hyoid bone from Austrolopithecus afarensis (Martinez, 2008), at a range of 500kya to 3.3mya. (de Boer, to appear). Justifications for the loss of laryngeal air sacs include infection, the ability to modify breathing patterns and reduce need for an anti-hyperventilating device (Hewitt et al, 2002), and the selection against air sacs as they are disadvantageous for subtle, timed, and distinct sounds (de Boer, to appear). Further, it has been suggested that the loss goes against the significant correlation of air sac retention to evolutionary growth in body mass (Hewitt et al., 2002).

I argue that the loss of air sacs may have occurred more recently (less than 600kya), as the loss of the bulla in the hyoid does not exclude the possibility of airs sacs, as in cervids, where laryngeal air sacs can herniate between two muscles (Frey et al., 2007). Further, the weight measurements of living species as a justification for the loss of air sacs despite a gain in body mass I argue to be unfounded given archaeological evidence, which suggests that the laryngeal air sacs may have been lost only after size reduction in Homo sapiens from Homo heidelbergensis.

Finally, I suggest two further justifications for loss of the laryngeal air sacs in homo sapiens. First, the linguistic niche of hunting in the environment in which early hominin hunters have been posited to exist – the savannah – would have been better suited to higher frequency, directional calls as opposed to lower frequency, multidirectional calls. The loss of air sacs would have then been directly advantageous, as lower frequencies produced by air sac vocalisations over bare ground have been shown to favour multidirectional over targeted utterances (Frey and Gebler, 2003). Secondly, the reuse of air stored in air sacs could have possibly been disadvantageous toward sustained, regular heavy breathing, as would occur in a similar hunting environment.

References:

Boer, B. de. (to appear). Air sacs and vocal fold vibration: Implications for evolution of speech.

Fitch, T. (2006). Production of Vocalizations in Mammals. Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Elsevier.

Frey, R, & Gebler, A. (2003). The highly specialized vocal tract of the male Mongolian gazelle (Procapra gutturosa Pallas, 1777–Mammalia, Bovidae). Journal of anatomy, 203(5), 451-71. Retrieved June 1, 2011, from http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1571182&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

Frey, Roland, Gebler, Alban, Fritsch, G., Nygrén, K., & Weissengruber, G. E. (2007). Nordic rattle: the hoarse vocalization and the inflatable laryngeal air sac of reindeer (Rangifer tarandus). Journal of Anatomy, 210(2), 131-159. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00684.x.

Martínez, I., Arsuaga, J. L., Quam, R., Carretero, J. M., Gracia, a, & Rodríguez, L. (2008). Human hyoid bones from the middle Pleistocene site of the Sima de los Huesos (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain). Journal of human evolution, 54(1), 118-24. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.07.006.

Hewitt, G., MacLarnon, A., & Jones, K. E. (2002). The functions of laryngeal air sacs in primates: a new hypothesis. Folia primatologica international journal of primatology, 73(2-3), 70-94. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12207055.

Sound good? I hope so! That’s all for now.

Human Biology special issue – Integrating Genetic and Cultural Evolutionary Approaches to Language

A special issue of Human Biology on language evolution is now online. However, you may need special access.