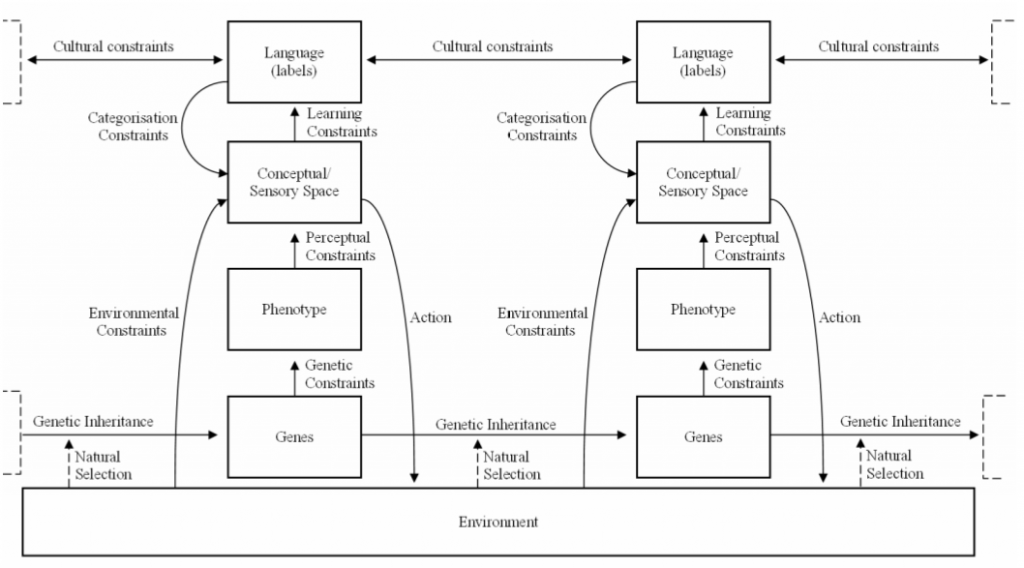

In 2007, Dan Dediu and Bob Ladd published a paper claiming there was a non-spurious link between the non-derived alleles of ASPM and Microcephalin and tonal languages. The key idea emerging from this research is one where certain alleles may bias language acquisition or processing, subsequently shaping the development of a language within a population of learners. Therefore, investigating potential correlations between genetic markers and typological features may open up new avenues of thinking in linguistics, particularly in our understanding of the complex levels at which genetic and cognitive biases operate. Specifically, Dediu & Ladd refer to three necessary components underlying the proposed genetic influence on linguistic tone:

[…] from interindividual genetic differences to differences in brain structure and function, from these differences in brain structure and function to interindividual differences in language-related capacities, and, finally, to typological differences between languages.”

That the genetic makeup of a population can indirectly influence the trajectory of language change differs from previous hypotheses into genetics and linguistics. First, it is distinct from attempts to correlate genetic features of populations with language families (e.g. Cavalli-Sforza et al., 1994). And second, it differs from Pinker and Bloom’s (1990) assertions of genetic underpinnings leading to a language-specific cognitive module. Furthermore, the authors do not argue that languages act as a selective pressure on ASPM and Microcephalin, rather this bias is a selectively neutral byproduct. Since then, there have been numerous studies covering these alleles, with the initial claims (Evans et al., 2004) for positive selection being under dispute (Fuli Yu et al., 2007), as well as any claims for a direct relationship between dyslexia, specific language impairment, working memory, IQ, and head-size (Bates et al., 2008).

A new paper by Dediu (2010) delves further into this potential relationship between ASPM/MCPH1 and linguistic tone, by suggesting this typological feature is genetically anchored to the aforementioned alleles. Generally speaking, cultural and linguistic processes will proceed on shorter timescales when compared to genetic change; however, in tandem with other recent studies (see my post on Greenhill et al., 2010), some typological features might be more consistently stable than others. Reasons for this stability are broad and varied. For instance, word-use within a population is a good indicator of predicting rates of lexical evolution (Pagel et al., 2007). Genetic aspects, then, may also be a stabilising factor, with Dediu claiming linguistic tone is one such instance:

From a purely linguistic point of view, tone is just another aspect of language, and there is no a priori linguistic reason to expect that it would be very stable. However, if linguistic tone is indeed under genetic biasing, then it is expected that its dynamics would tend to correlate with that of the biasing genes. This, in turn, would result in tone being more resistant to ‘regular’ language change and more stable than other linguistic features.

Continue reading “Genetic Anchoring, Tone and Stable Characteristics of Language”