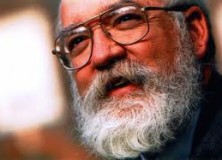

I want to look at two recent pieces by Daniel Dennett. One is a formal paper from 2009, The Cultural Evolution of Words and Other Thinking Tools (Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology, Volume LXXIV, pp. 1-7, 2009). The other is an informal interview from January of 2013, The Normal Well-Tempered Mind. What interests me is how Dennett thinks about computation in these two pieces.

In the first piece Dennett seems to be using the standard-issue computational model/metaphor that he’s been using for decades, as have others. This is the notion of a so-called von Neumann machine with a single processor and a multi-layer top-down software architecture. In the second and more recent piece Dennett begins by asserting that, no, that’s not how the brain works, I was wrong. At the very end I suggest that the idea of the homuncular meme may have served Dennett as a bridge from the older to the more recent conception.

Words, Applets, and the Digital Computer

As everyone knows, Richard Dawkins coined the term “meme” as the cultural analogue to the biological gene, or alternatively, a virus. Dennett has been one of the most enthusiastic academic proponents of this idea. In his 2009 Cold Spring Harbor piece Dennett concentrates his attention on words as memes, perhaps the most important class of memes. Midway through the paper tells he us that “Words are not just like software viruses; they are software viruses, a fact that emerges quite uncontroversially once we adjust our understanding of computation and software.”

Those first two phrases, before the comma, assert a strong identification between words and software viruses. They are the same (kind of) thing. Then Dennett backs off. They are the same, providing of course, that “we adjust our understanding of computation and software.” Just how much adjusting is Dennett going to ask us to do?

This is made easier for our imaginations by the recent development of Java, the software language that can “run on any platform” and hence has moved to something like fixation in the ecology of the Internet. The intelligent composer of Java applets (small programs that are downloaded and run on individual computers attached to the Internet) does not need to know the hardware or operating system (Mac, PC, Linux, . . .) of the host computer because each computer downloads a Java Virtual Machine (JVM), designed to translate automatically between Java and the hardware, whatever it is.

The “platform” on which words “run” is, of course, the human brain, about which Dennett says nothing beyond asserting that it is there (a bit later). If you have some problems about the resemblance between brains and digital computers, Dennett is not going to say anything that will help you. What he does say, however, is interesting.

Notice that he refers to “the intelligent composer of Java applets.” That is, the programmer who writes those applets. Dennett knows, and will assert later on, that words are not “composed” in that way. They just happen in the normal course of language use in a community. In that respect, words are quite different from Java applets. Words ARE NOT explicitly designed; Java applets ARE. Those Java applets seem to have replaced computer viruses in Dennett’s exposition, for he never again refers to them, though they (viruses) figured emphatically in the topic sentence of this paragraph.

The JVM is “transparent” (users seldom if ever encounter it or even suspect its existence), automatically revised as needed, and (relatively) safe; it will not permit rogue software variants to commandeer your computer.

Computer viruses, depending on their purpose, may also be “transparent” to users, but, unlike Java applets, they may also commandeer your computer. And that’s not nice. Earlier Dennett had said:

Our paradigmatic memes, words, would seem to be mutualists par excellence, because language is so obviously useful, but we can bear in mind the possibility that some words may, for one reason or another, flourish despite their deleterious effects on this utility.

Perhaps that’s one reason Dennett abandoned his talk of computer viruses in favor of those generally helpful Java applets. Continue reading “Watch Out, Dan Dennett, Your Mind’s Changing Up on You!”