I’ve uploaded another document: Sharing Experience: Computation, Form, and Meaning in the Work of Literature. You can download it from Academia.edu:

https://www.academia.edu/28764246/Sharing_Experience_Computation_Form_and_Meaning_in_the_Work_of_Literature

It’s considerably revised from a text I’d uploaded a month ago: Form, Event, and Text in an Age of Computation. You might also look at my post, Obama’s Affective Trajectory in His Eulogy for Clementa Pinckney, which could have been included in the article, but I’m up against a maximum word count as I am submitting the article for publication. You might also look at the post, Words, Binding, and Conversation as Computation, which figured heavily in my rethinking.

Here’s the abstract of the new article, followed by the TOC and the introduction:

Abstract

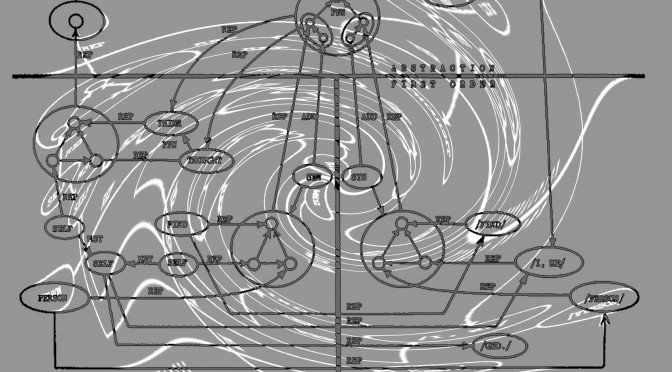

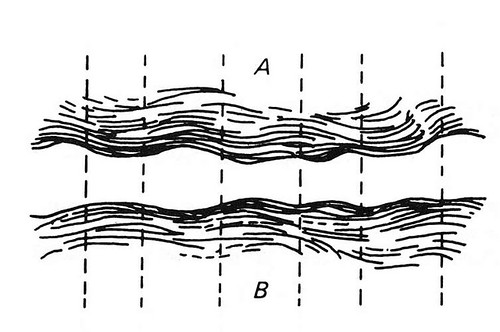

It is by virtue of its form that a literary work constrains meaning so that it can be a vehicle for sharing experience. Form is thus an intermediary in Latour’s sense, while meaning is a mediator. Using fragments of a cognitive network model for Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129 we can distinguish between (1) the mind/brain cognitive system, (2) the text considered merely as a string of signifiers, and (3) the path one computes through (1) under constraints imposed by (2). As a text, Obama’s Eulogy for Clementa Pinckney is a ring-composition; as a performance, the central section is clearly marked by audience response. Recent work on synchronization of movement and neural activity across communicating individuals affords insight into the physical substrate of intersubjectivity. The ring-form description is juxtaposed to the performative meaning identified by Glenn Loury and John McWhorter.

CONTENTS

Introduction: Speculative Engineering 2

Form: Macpherson & Attridge to Latour 3

Computational Semantics: Network and Text 6

Obama’s Pinckney Eulogy as Text 10

Obama’s Pinckney Eulogy as Performance 13

Meaning, History, and Attachment 18

Coda: Form and Sharability in the Private Text 20

Introduction: Speculative Engineering

The conjunction of computation and literature is not so strange as it once was, not in this era of digital humanities. But my sense of the conjunction is differs from that of computational critics. They regard computation as a reservoir of tools to be employed in investigating texts, typically a large corpus of texts. That is fine [1].

Digital critics, however, have little interest in computation as a process one enacts while reading a text, the sense that interests me. As the psychologist Ulric Neisser pointed out four decades ago, it was computation that drove the so-called cognitive revolution [2]. Much of the work in cognitive science is conducted in a vocabulary derived computing and, in many cases, involves computer simulations. Prior to the computer metaphor we populated the mind with sensations, perceptions, concepts, ideas, feelings, drives, desires, signs, Freudian hydraulics, and so forth, but we had no explicit accounts of how these things worked, of how perceptions gave way to concepts, or how desire led to action. The computer metaphor gave us conceptual tools for constructing models with differentiated components and processes meshing like, well, clockwork. Moreover, so far as I know, computation of one kind or another provides the only working models we have for language processes.

My purpose in this essay is to recover the concept of computation for thinking about literary processes. For this purpose it is unnecessary either to believe or to deny that the brain (with its mind) is a digital computer. There is an obvious sense in which it is not a digital computer: brains are parts of living organisms; digital computers are not. Beyond that, the issue is a philosophical quagmire. I propose only that the idea of computation is a useful heuristic: it helps us think about and systematically describe literary form in ways we haven’t done before.

Though it might appear that I advocate a scientific approach to literary criticism, that is misleading. Speculative engineering is a better characterization. Engineering is about design and construction, perhaps even Latourian composition [3]. Think of it as reverse-engineering: we’ve got the finished result (a performance, a script) and we examine it to determine how it was made [4]. It is speculative because it must be; our ignorance is too great. The speculative engineer builds a bridge from here to there and only then can we find out if the bridge is able to support sustained investigation.

Caveat emptor: This bridge is of complex construction. I start with form, move to computation, with Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129 as my example, and then to President Obama’s Eulogy for Clementa Pinckney. After describing its structure (ring-composition) I consider the performance situation in which Obama delivered it, arguing that those present constituted a single physical system in which for sharing experience. I conclude by discussing meaning, history, and attachment.

References

[1] William Benzon, “The Only Game in Town: Digital Criticism Comes of Age,” 3 Quarks Daily, May 5, 2014, http://www.3quarksdaily.com/3quarksdaily/2014/05/the-only-game-in-town-digital-criticism-comes-of-age.html

[2] Ulric Neisser, Cognition and Reality: Principles and Implications of Cognitive Psychology (San Francisco: W. H. Freeman, 1976), 5-6.

[3] Bruno Latour, “An Attempt at a ‘Compositionist Manifesto’,” New Literary History 41 (2010), 471-490.

[4] For example, see Steven Pinker, How the Mind Works (New York: W.W. Norton & company, Inc., 1997), 21 ff.

![What’s in a Name? – “Digital Humanities” [#DH] and “Computational Linguistics”](http://www.replicatedtypo.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/20160514-_IGP6641-e1464037525388-672x372.jpg)