This post is about terminology, but also about things – in particular, an abstract thing – and measurements of those things. The things and measurements arise in the study of cultural evolution.

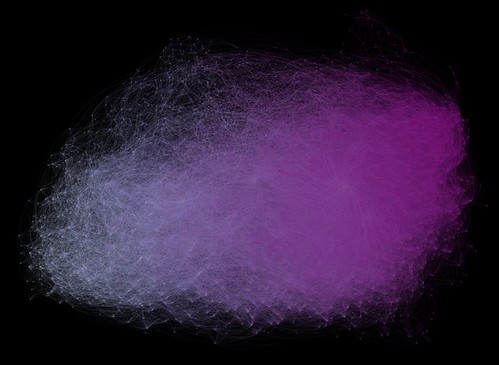

Let us start with a thing. What is this?

If you are a regular reader here at New Savanna you might reply: Oh, that’s the whatchamacallit from Jocker’s Macroanalysis. Well, yes, it’s an illustration from Macroanalysis. But that’s not quite the answer I was looking for. But let’s call that answer a citation and set it aside.

Let’s ask the same question, but of a different object: What’s this?

I can imagine two answers, both correct, each it its own way:

1. It’s a photo of the moon.

2. The moon.

Strictly speaking, the first is correct and the second is not. It IS a photograph, not the moon itself. But the second answer is well within standard usage.

Notice that the photo does not depict the moon in full (whatever that might mean), no photograph could. That doesn’t change the fact that it is the moon that is depicted, not the sun, or Jupiter, or Alpha Centauri, or, for that matter, Mickey Mouse. We do not generally expect that representations of things should exhaust those things.

Now let us return to the first image and once again ask: What is this? I want two answers, one to correspond with each of our answers about the moon photo. I’m looking for something of the form:

1. A representation of X.

2. X.

Let us start with X. Jockers was analyzing a corpus of roughly 3300 19th century Anglophone novels. To do that he evaluated each of them on each of 600 features. Since those evaluations can be expressed numerically Jockers was able to create a 600-dimensional space in which teach text occupies a single point. He then joined all those points representing texts that are relatively close to one another. Those texts are highly similar with respect to the 600 features that define the space.

The result is a directed graph having 3300 nodes in 600 dimensions. So, perhaps we can say that X is a corpus similarity graph. However, we cannot see in 600 dimensions so there is no way we can directly examine that graph. It exists only as an abstract object in a computer. What we can do, and what Jockers did, is project a 600D object into two dimensions. That’s what we see in the image.

Now we have:

1. A 2D representation of a corpus similarity graph.

2. A corpus similarity graph.

But that corpus didn’t come out of nowhere. Each text in the corpus was written by someone, published by someone else, and read by others. Some were read by a relative handful of people while others have been read by 100s of thousands, perhaps even millions, over the years. Some of them are still being read, while most of them are forgotten.

However it is that Jockers was able to assemble this corpus in the early 21st century and then analyze, it originated in a rich and complex historical process that evolved through the 19th century Anglophone world. Thus we might argue that is a component of something like the collective 19th century Anglophone mind. That’s what philosophers at the time thought of as Geist or Spirit – hence the title of this post (for further explanation, see this post, and this one).

For obvious reasons I do not want to introduce either term as a term of art in the study of cultural evolution, but it’s not clear to me just what I should call that object. For the moment let’s just call it the 19th century collective mind (though see the entry for “reticulum” in my list of terms for cultural evolution). That gives us a third answer to our question: What is this?

3. The 19th century collective mind.

And just as the moon photo doesn’t represent the moon in full, so that image doesn’t represent the 19th century collective mind in full. It is just some aspect of that thing, that abstract object (one of Tim Morton’s hyperobjects?), that 19th century collective mind.

With that, however, we can proceed on.

Two weeks ago I did a post on a paper by Olivier Morin & Alberto Acerbi, Birth of the cool: a two-centuries decline in emotional expression in Anglophone fiction. They document “a decrease in emotionality in English-speaking literature starting plausibly in the nineteenth century.” Are they not measuring the 19th century collective mind? That is, are they not measuring the cultural object that Jocker’s represented in his corpus similarity graph, which is in turn depicted in the illustration at the head of this post?

In a similar fashion Ryan Heuser and Long Le-Khac documented a shift from abstract to concrete words, from telling to showing in 19th century British novels, A Quantitative Literary History Of 2,958 Nineteenth-Century British Novels: The Semantic Cohort Method (68 page PDF). Is that not another measurement of that same cultural object, the 19th century collective mind?

But why do I say that Jockers is representing that object in his visualization while Morin and Acerbi, on the one hand, and Heuser and Le-Khac, in the other, are measuring that object? Is that a tenable distinction? If so, on what basis? It conventional to assert that my photograph represents, rather than measures, the moon. Is that mere semantics?

I don’t know.

The first thing to remember is that human language consists of words (symbols) some of which refer to reality (objects). Others do not refer to objects, because not all the words are ontologically committed. They are however content words, basically, verbs, nouns and adjectives. Now what they represent as the bottom line is relations, objects and properties. When you use a language you enter a relation, by entering a relation (you need a verb here) you relate yourself to what you see (sense). You may relate your sensation to a linguistic device and as soon as you do that you perform measurements. All contacting is measurement regardless of whether you have a unit of measurement or a quantity measured. Now whether an object is represented by a linguistic object is a matter of your comprehension (culture). As logic among other things requires, you want one on one relationship with the world (objects) hence you make a contact, you make a measurement. Some of the contacts we make are already metrified and have units of measurements, others do not.You relate yourself to the world and you relate yourself to yourself and it is hardly possible to give an account verbally of what you experience within. So in many cases you have two verbs (predicates) in a statement to indicate what you mean in terms of comprehension.No single word or single proposition has any meaning. You need to have an antecedent and an aftermath of anything communicated. See the DEED paradigm by D. Crystal.

“Ce n’est pas une pipe” comes to mind.

Ferenc, let me give a structuralist counter-argument: words are already in a relation independent of predication, by virtue of their “relation” of difference to every other word in the language. Ontology (as I understand it, mostly in the Barry Smith sense of the field) misses this in its…well, in so many ways–but, certainly by insisting that the “term” (in OBO terms, no pun intended) has no meaning, but only the concept.

Concerning the questions in my last paragraph, consider a different example. There’s a small rubber ball over there on the floor. That’s an object. It’s 3 cm in diameter. That’s a measurement of that object. That’s the distinction I’m interested in. In this case the object is available to the senses and the measurement is simple to perform.

In the post I’m dealing with things that are not observable by the senses and cannot be measured in any direct way. What we’re dealing with is not so obvious. In fact, it’s not obvious that we’re dealing with anything at all. It may all be artifacts of lousy data and poor computational procedures. I am, however, assuming that we’re looking at something real. Is what Jockers’ depicts like the apple and the others are measuring the apple? Maybe it’s all measurement, measurement of cultural evolution.

Concepts and/or abstract nouns (words) are a headache as probably they are not of monadic nature. You cannot go very far by being in the abstract because it is the concrete that you can grasp. There is an abstract-concrete and a generic-specific continuum where you move along as your intent to get understood requires. Most of the abstract word just do not make any sense and they are invented to feed bullshit to the naive audience.What is missing from theses treaties is that there are mental operations that complement each other and they need to be seen clearly to understand what a theorist’s rant is about. Do not trust any -ism, and similar fabrications and especially do not substantize them in order to be able to measure them. Think of the concepts of Physics like speed equals distance over time. Both distance and time call for a unit – we agree on one for each. But forget the units what you get is speed 1=1/1 which takes you nowhere. You cannot even visualize anything before you use the mental operation reification, On the other hand impersonation, personalization, etc are a real hazard. Look at isolation, generalization, abstraction, specification, interpretation, formalization, unification, etc. how your concepts evolve and mutate as needed to make yourself understood. The most disgusting texts I have ever read are the welcome speeches at the opening ceremonies of fine art exhibition. Get them translated into any other language and you will see what i mean..

The ultimate measurement is (a relation) being a part of the world – two aspects 1.ego – self consciousness – cogiito 2.the object the ego focuses on, relates to – ergo sum the existing world that is. The ultimate relation is YOU being either inside or outside. You cannot be at both places at the same time.Law of the excluded middle.Now QT is a different story.

From the beginning of my entry, “Ontology of Common Sense” in Hans Burkhardt and Barry Smith, eds. Handbook of Metaphysics and Ontology, Muenchen: Philosophia Verlag GmbH, 1991, pp. 159-161.

This is fine, thank you. Ontology as the word says is a collection of things that exist. The linguistic means to identify things that exist are nouns and noun phrases. The greatest inventory of objects defined in terms of nouns and noun phrases is the collection of Extended Named Entities http://nlp.cs.nyu.edu/ene/. The composition of the English language in terms of word categories shows that there are hundreds of thousands of nouns, somewhat less adjectives and just a few thousand verbs only.

Now in my view abstract nouns whether created from verbs or otherwise indicate abstract objects along with adjectives and verbs that are also abstract since they represent properties and relations. The are abstract, because they are generated by abstracting them from various statements about objects. Also, many of them are simple analogies, or what is worse, metaphors which are false analogies.

Remember that all languages are tautologies and nothing has any meaning on its own. You need to connect your abstract nouns (concepts, etc.) to experience of all kinds. Neither the terminology of a scientist or the argo of a layman is less superior as long as they agree on the identity of the reference, regardless of the framework that it is described in. But naturally, the verification and consolidation of such common ground is practically difficult to perform. Therefore usage is a battlefield and harmonization of terminology (and solving the legacy problem) must be grounded in a different theoretical setup which includes the concept of mental operations complete with its corollaries.

NOTE: For reasons I don’t understand, I can no longer access this site from home. At the moment I’m visiting my sister in Philadelphia and can access it fine. But I’m returning home shortly so this will be my last comment here until I can figure out what’s going on.