This is a guest post by Cole Robertson.

Readers of this blog are likely to be familiar with controversy surrounding Keith Chen’s (2013) findings suggesting that the way a language deals with the future tense affects speakers’ economic decisions. A new study by a group of Austrian and German economists has recently added experimental evidence to the growing body of research on the issue.

The study focuses on German and Italian. As with English, Italian requires a speaker to mark the future tense, e.g. “it will rain tomorrow” not simply “it rains tomorrow.” German, on the other hand, requires no such marking—speakers are free to say the equivalent of “it rains tomorrow.”

Chen hypothesized that speaking about future event using the present tense, as in languages like German, could make the future seem more immediate. He suggested this might cause speakers to value future events more highly than speakers of languages like Italian. Indeed, using large-scale statistical methods, Chen found that speakers of languages like German (with no separate future tense) tend to smoke less, be less obese, engage in safer sex practices, retire with more money, and save more per year.

His findings have been criticized on various grounds, from potential inconsistencies in the data, to small number bias in the original dataset, to the fact that the hypothesis could easily have been formulated the other way around, to the fact that Chen’s classification of how languages refer to the future may be overly simplistic.

However, most criticism has centred around the potential spuriousness of the correlation between future tense marking and future orientated behaviour. Commentators have been quick to point out that since cultural traits tend to be inherited in packages, it’s likely that future orientation and future tense reference are causally unrelated. In fact, Roberts, Winters and Chen (2015) found that the correlation dropped below significance when controlling for cultural relatedness (for some if not all their statistical tests). As such, the jury may yet be hung until experimental evidence confirms (or doesn’t) Chen’s findings.

The new study attempts to do exactly this. Though not yet peer reviewed, it was recently opened to comments and criticism as a discussion paper, as apparently is common in the discipline of economics. You can read it here.

The paper takes advantage of bilingualism in the city of Meran in the autonomous province of South Tyrol in Northern Italy, where roughly 50% of the population speaks German and the other 50% speaks Italian. Hoping to mitigate the cultural confounds that plagued Chen’s (2013) findings, the authors argue that since the German- and Italian-speaking citizens of Meran share a home city, they also share a similar enough cultural milieu that experimenting on them can isolate the effects of their language on how they value future events.

The experiment worked like this: children were presented with three choices. In each of the choices they could either accept two tokens at the time of the test or opt instead to receive a greater number of tokens four weeks in the future (the ‘patient’ choice). The future rewards were three, four, or five tokens. So in other words, children had to choose three times, between: 1) two tokens now and three tokens in four weeks, 2) two tokens now and four tokens in four weeks, and 3) two tokens now and five tokens in four weeks.

One of these choices was randomly selected for their actual pay-out, and they could then trade the tokens for a selection of small toys and items the experimenters had on offer. As control variables, they also measured IQ relative to cohort, the income and education of the parents, the children’s risk-taking propensity, average housing prices in the area of the school, and whether the children had friends who spoke another language.

In presenting their results they begin with a sample of just those students both of whose parents speak either German or Italian (n=860). They then progressively add students from different linguistic groups to their sample. They start with (n=203) students from bilingual German-Italian households, then add (n=261) students from household where both parents speak a language which has a future tense (like Italian) but which is not Italian. They then treat these delineations as categorical variables and use both regressions and non-parametric tests to see whether a child’s language category affects their tendency to wait for future rewards.

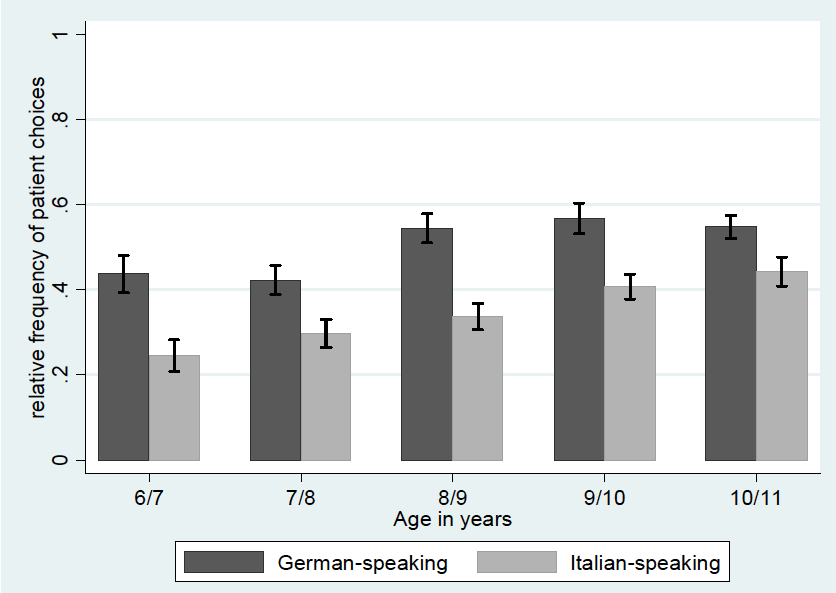

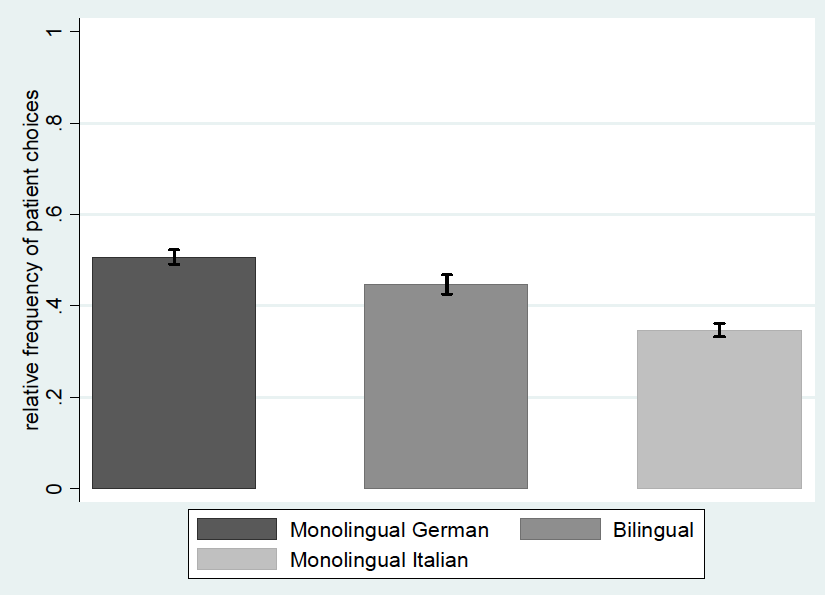

Their results suggest that it does. In the first sample, the German-speaking children were more likely to wait for the future reward than the Italian-speaking children, across all age groups and when including the host of control variables. Moreover, when they added the German-Italian bilingual group to the sample, their tendency to wait for future rewards was intermediate between the all-Italian and all-German children. Finally, they find that the (n=261) student who speak a language which marks the future tense, but which is not Italian, are significantly less likely to wait for future rewards compared to German speaking children, but are not significantly different from the Italian cohort.

They also separately analyse (n=91) students one of whose parents speak German or Italian and the other of whose parents (except for 5 cases) speaks a language which, like Italian, mandates marking of the future tense. They find that children with one German-speaking parent and one future-tense-marking parent are more likely to wait for future rewards than children with one Italian-speaking parent and another future-tense-marking parent.

Should these results be trusted? There are some strange statistics in the paper; throughout, they use multiple Mann-Whitney U Tests when comparing more than two groups, but never report any kind of post-hoc correction for multiple comparisons. With some p-values reported at the < .05 level, this could be problematic for some of their findings. Whilst their regressions would not be affected, I have to assume they present non-parametric tests because at least some of their data violate normality assumptions.

However, their results are corroborated by a second experiment which uses a slightly different discounting task and which only has two groups (all German and all Italian) and is therefore not affected by any apparent failure to correct for multiple comparisons.

They also include several other robustness tests. They make sure risk attitudes (which they find predict propensity to wait for future pay outs) are not correlated with language group (they aren’t). Although, whether this reveals anything more than their multiple regressions is unclear, since they already revealed a result whilst controlling for any correlation between the two variables. Additionally, they survey (n=177) Meraners to check whether there are any differences between the Italian and German populations in terms of their attitudes towards the importance of “thrift” and “patience.” Finding no such differences, they argue that this supports the conclusions that there are no cultural differences confounding their findings.

However, can we really trust self-reported estimations of the importance of thrift and patience? Most people know that they should say these are important, so is it really possible to rule out implicit demand characteristics that might undermine actual differences between the two language groups?

In fact, even according to the authors themselves, the German- and Italian-speaking populations in Meran remain linguistically and culturally “fairly segregated, with different media (like newspapers or TV channels) and leisure activities (like different football clubs)” (Sutter et al, 2015 p. 5). Schools are evidently also segregated by language, teaching either in Italian or German, and no schools to-date have an equal number of Italian and German students.

Indeed, relations between the Italian- and German-speaking people in South Tyrol may not be as copasetic as they are portrayed to be by the authors. In fact, there is evidence that tensions have been simmering since Mussolini attempted to “Italianise” the area in the 1930s by mass relocating Southern Italians northwards. Activism in the 1960s (including violent conflict) eventually lead to a bilingual language accord, and significant autonomy from Rome in 1972. Today, German speakers accuse Italian authorities of racism and “linguistic imperialism”, whilst Italians accuse Germans of receiving preferential treatment. There have even been arguments over the language of signage on alpine hiking routes , which eventually sparked a felt-tipped graffiti war that quickly degenerated into racial profanity. As such, is it really possible to rule out cultural confounds? As a Canadian who has lived in Montreal, the epicentre of Canadian French-English bilingual conflict, I can personally attest to the fact that geography and culture are not the same thing.

Moreover, the experiment does not actually manipulate children’s responses; it merely applies the same test to children from different language groups. What is strange is that there may actually be an unreported manipulation in the experiment. Since the authors only state that the test prompts were given in the child’s “mother tongue”, I would assume that some of the (n=203) bilingual children were tested in Italian and some in German. This means that the researchers hopefully have (or might be able to get) data on whether the language of the test prompt affected the children’s propensity to wait for future rewards.

Until they include these results in the analysis, their findings seem to be subject to the same criticisms levelled against Chen (2013). In other words, they may be picking up on a spurious correlation resulting from the fact that thriftiness and tense structure, whilst causally unrelated, could have been co-inherited from antecedent cultural groups.

If the Italian and German populations in South Tyrol are as alienated and segregated as they seem to be, it’s entirely possible that the German-speakers inherited increased thriftiness as well as a language without a future tense, whilst the Italian-speakers inherited decreased thriftiness as well as a language with a future tense. They need not be causally related, and the speakers’ geographical proximity may not have been enough to override these packages of traits. Until we see a language-based manipulation of future-orientated behaviour, the issue of whether tense affects how we value future events will remain unresolved.

References

Chen, M. K. (2013). “The Effect of Language on Economic Behavior: Evidence from Savings Rates, Health Behaviors, and Retirement Assets.” American Economic Review 103(2): 690-731.

Roberts, S. G., Winters, J. & Chen, M. K. (2015). “Future Tense and Economic Decisions: Controlling for Cultural Evolution.” PLoS One 10(7): e0132145.

Sutter, M., et al. (2015). “The Effect of Language on Economic Behavior: Experimental Evidence from Children’s Intertemporal Choices.” IZA Discussion Paper Series 9383.

Cole Robertson lives and works in Oxford, where he is completing a PhD focusing on inter-linguistic tense differences and future-orientated behavior, but he’s generally interested in how language interfaces with other cognitive, perceptual, and behavioural systems, as well as language revitalization and language evolution. He’s an avid rock climber and mountaineer and once spent two days eating nothing but sausages cooked over a candle whilst waiting out a storm. He grew up in Vancouver, Canada.

Cole Robertson lives and works in Oxford, where he is completing a PhD focusing on inter-linguistic tense differences and future-orientated behavior, but he’s generally interested in how language interfaces with other cognitive, perceptual, and behavioural systems, as well as language revitalization and language evolution. He’s an avid rock climber and mountaineer and once spent two days eating nothing but sausages cooked over a candle whilst waiting out a storm. He grew up in Vancouver, Canada.