What do we mean when we talk about the “cognitive foundations” of language or the “cognitive principles” behind linguistic phenomena? And how can we tap into the cognitive underpinnings of language? These questions lie at the heart of a workshop that Michael Pleyer and I are going to propose for the next International Cognitive Linguistics Conference. Here’s our Call for Papers:

Construal and language dynamics: Interdisciplinary and cross-linguistic perspectives on linguistic conceptualization

– Workshop proposal for the 15th International Cognitive Linguistics Conference, Nishinomiya, Japan, August 6–11, 2019 –

Convenors:

Stefan Hartmann, University of Bamberg

Michael Pleyer, University of Koblenz-Landau

The concept of construal has become a key notion in many theories within the broader framework of Cognitive Linguistics. It lies at the heart of Langacker’s (1987, 1991, 2008) Cognitive Grammar, but it also plays a key role in Croft’s (2012) account of verbal argument structure as well as in the emerging framework of experimental semantics (Bergen 2012; Matlock & Winter 2015). Indirectly it also figures in Talmy’s (2000) theory of cognitive semantics, especially in his “imaging systems” approach (see e.g. Verhagen 2007).

According to Langacker (2015: 120), “[c]onstrual is our ability to conceive and portray the same situation in alternate ways.” From the perspective of Cognitive Grammar, an expression’s meaning consists of conceptual content – which can, in principle, be captured in truth-conditional terms – and its construal, which encompasses aspects such as perspective, specificity, prominence, and dynamicity. Croft & Cruse (2004) summarize the construal operations proposed in previous research, arriving at more than 20 linguistic construal operations that are seen as instances of general cognitive processes.

Given the “quantitative turn” in Cognitive Linguistics (e.g. Janda 2013), the question arises how the theoretical concepts proposed in the foundational works of the framework can be empirically tested and how they can be refined on the basis of empirical findings. Much work in the domains of experimental linguistics and corpus linguistics has established a research cycle whereby hypotheses are generated on the basis of theoretical concepts from Cognitive Linguistics, such as construal operations, and then tested using behavioral and/or corpus-linguistic methods (see e.g. Hilpert 2008; Matlock 2010; Schönefeld 2011; Matlock et al. 2012; Krawczak & Glynn forthc., among many others).

Arguably one of the most important testing grounds for theories of linguistic construal is the domain of language dynamics. Recent years have seen increasing convergence between Cognitive-Linguistic theories on the one hand and theories conceiving of language as a complex adaptive system on the other (Beckner et al. 2009; Frank & Gontier 2010; Fusaroli & Tylén 2012; Pleyer 2017). In this framework, language can be understood as a dynamic system unfolding on the timescales of individual learning, socio-cultural transmission, and biological evolution (Kirby 2012, Enfield 2014). Linguistic construal operations can be seen as important factors shaping the structure of language both on a historical timescale and in ontogenetic development (e.g. Pleyer & Winters 2014).

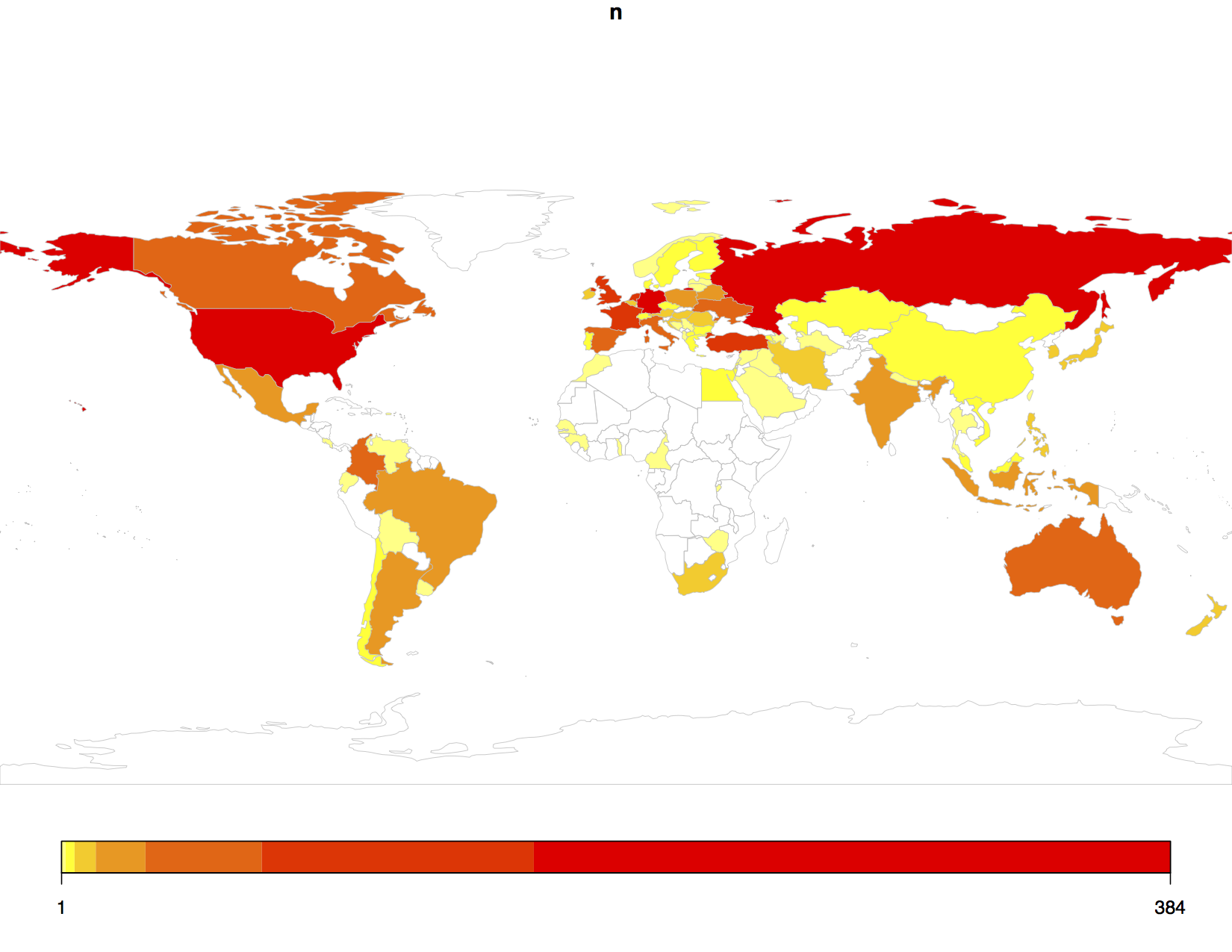

Empirical studies of language acquisition, language change, and language variation can therefore help us understand the nature of linguistic construal operations and can also contribute to refining theories of linguistic construal. Interdisciplinary and cross-linguistic perspectives can prove particularly insightful in this regard. Findings from cognitive science and developmental psychology can contribute substantially to our understanding of the cognitive principles behind language dynamics. Cross-linguistic comparison can, on the one hand, lead to the discovery of striking similarities across languages that might point to shared underlying cognitive principles (e.g. common pathways of grammaticalization, see e.g. Bybee et al. 1994, or similarities in the domain of metaphorical construal, see Taylor 2003: 140), but it can also safeguard against premature generalizations from findings obtained in one single language to human cognition at large (see e.g. Goschler 2017).

For our proposed workshop, we invite contributions that explicitly connect theoretical approaches to linguistic construal operations with empirical evidence from e.g. corpus linguistics, experimental studies, or typological research. In line with the cross-linguistic outlook of the main conference, we are particularly interested in papers that compare linguistic construals across different languages. Also, we would like to include interdisciplinary perspectives from the behavioural and cognitive sciences.

The topics that can be addressed in the workshop include, but are not limited to,

- the role of construal operations such as perspectivation and specificity in language production and processing;

- the acquisition and diachronic change of linguistic categories;

- the question of whether individual construal operations that have been proposed in the literature are cognitively realistic (see e.g. Broccias & Hollmann 2007) and whether they can be tested empirically;

- the refinement of construal-related concepts such as “salience” or “prominence” based on empirical findings (see e.g. Schmid & Günther 2016);

- the relationship between linguistic construal operations and domain-general cognitive processes;

- the relationship between empirical observations and the conclusions we draw from them about the organization of the human mind, including the viability of concepts such as the “corpus-to-cognition” principle (see e.g. Arppe et al. 2010) or the mapping of behavioral findings to cognitive processes.

Please send a short abstract (max. 1 page excl. references) and a ~100-word summary to construal.iclc15@gmail.com by August 31st, 2018 September 10th, 2018. We will inform all potential contributors in early September whether your paper can be included in our workshop proposal. If we are unable to accommodate your submission, you can of course submit it to the general session of the conference. The same applies if our workshop proposal as a whole is rejected.

References

Arppe, Antti, Gaëtanelle Gilquin, Dylan Glynn, Martin Hilpert & Arne Zeschel. 2010. Cognitive Corpus Linguistics: Five Points of Debate on Current Theory and Methodology. Corpora 5(1). 1–27.

Beckner, Clay, Richard Blythe, Joan Bybee, Morten H. Christiansen, William Croft, Nick C. Ellis, John Holland, Jinyun Ke, Diane Larsen-Freeman & Tom Schoenemann. 2009. Language is a Complex Adaptive System: Position Paper. Language Learning 59 Suppl. 1. 1–26.

Bergen, Benjamin K. 2012. Louder than Words: The New Science of How the Mind Makes Meaning. New York: Basic Books.

Broccias, Cristiano & Willem B. Hollmann. 2007. Do we need Summary and Sequential Scanning in (Cognitive) Grammar? Cognitive Linguistics 18. 487–522.

Bybee, Joan L., Revere Perkins & William Pagliuca. 1994. The Evolution of Grammar: Tense, Aspect, and Modality in the Languages of the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Croft, William & Alan Cruse. 2004. Cognitive Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Enfield, N.J. 2014. Natural causes of language: frames, biases, and cultural transmission. (Conceptual Foundations of Language Science 1). Berlin: Language Science Press.

Frank, Roslyn M. & Nathalie Gontier. 2010. On Constructing a Research Model for Historical Cognitive Linguistics (HCL): Some Theoretical Considerations. In Margaret E. Winters, Heli Tissari & Kathryn Allan (eds.), Historical Cognitive Linguistics, 31–69. (Cognitive Linguistics Research 47). Berlin, New York: De Gruyter.

Fusaroli, Riccardo & Kristian Tylén. 2012. Carving language for social coordination: A dynamical approach. Interaction Studies 13(1). 103–124.

Goschler, Juliana. 2017. A contrastive view on the cognitive motivation of linguistic patterns: Concord in English and German. In Stefan Hartmann (ed.), Yearbook of the German Cognitive Linguistics Association 2017, 119–128.

Hilpert, Martin. 2008. New evidence against the modularity of grammar: Constructions, collocations, and speech perception. Cognitive Linguistics 19(3). 491–511.

Janda, Laura (ed.). 2013. Cognitive Linguistics: The Quantitative Turn. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter.

Kirby, Simon. 2012. Language is an Adaptive System: The Role of Cultural Evolution in the Origins of Structure. In Maggie Tallerman & Kathleen R. Gibson (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Language Evolution, 589–604. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Krawczak, Karolina & Dylan Glynn. forthc. Operationalising construal. Of / about prepositional profiling for cognition and communication predicates. In C. M. Bretones Callejas & Chris Sinha (eds.), Construals in language and thought. What shapes what? Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Langacker, Ronald W. 1987. Foundations of Cognitive Grammar. Vol. 1: Theoretical Prerequisites. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Langacker, Ronald W. 1991. Foundations of Cognitive Grammar. Vol. 2: Descriptive Application. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Langacker, Ronald W. 2008. Cognitive Grammar: A Basic Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Langacker, Ronald W. 2015. Construal. In Ewa Dąbrowska & Dagmar Divjak (eds.), Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics, 120–142. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter.

Matlock, Teenie. 2010. Abstract Motion is No Longer Abstract. Language and Cognition 2(2). 243–260.

Matlock, Teenie, David Sparks, Justin L. Matthews, Jeremy Hunter & Stephanie Huette. 2012. Smashing New Results on Aspectual Framing: How People Talk about Car Accidents. Studies in Language 36(3). 700–721.

Matlock, Teenie & Bodo Winter. 2015. Experimental Semantics. In Bernd Heine & Heiko Narrog (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Analysis, 771–790. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pleyer, Michael & James Winters. 2014. Integrating Cognitive Linguistics and Language Evolution Research. Theoria et Historia Scientiarum 11. 19–43.

Schmid, Hans-Jörg & Franziska Günther. 2016. Toward a Unified Socio-Cognitive Framework for Salience in Language. Frontiers in Psychology 7. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01110 (31 March, 2018).

Schönefeld, Doris (ed.). 2011. Converging evidence: methodological and theoretical issues for linguistic research. (Human Cognitive Processing 33). Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Talmy, Leonard. 2000. Toward a Cognitive Semantics. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Taylor, John R. 2003. Linguistic Categorization. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Verhagen, Arie. 2007. Construal and Perspectivization. In Dirk Geeraerts & Hubert Cuyckens (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics, 48–81. Oxford: Oxford University Press.