In an attempt to write out my thoughts for others instead of continually building them up in saved stickies, folders full of .pdfs, and hastily scribbled lecture notes, as if waiting for the spontaneous incarnation of what looks increasingly like a dissertation, I’m going to give a glimpse today of what I’ve been looking into recently. (Full disclosure: I am not a biologist, and was told specifically by my High School teacher that it would be best if I didn’t do another science class. Also, I liked Latin too much, which explains the title.)

In an attempt to write out my thoughts for others instead of continually building them up in saved stickies, folders full of .pdfs, and hastily scribbled lecture notes, as if waiting for the spontaneous incarnation of what looks increasingly like a dissertation, I’m going to give a glimpse today of what I’ve been looking into recently. (Full disclosure: I am not a biologist, and was told specifically by my High School teacher that it would be best if I didn’t do another science class. Also, I liked Latin too much, which explains the title.)

It all started, really, with trying to get my flatmate Jamie into research blogging. His intended career path is mycology, where there are apparently fewer posts available for graduate study than in Old English syntax. As he was setting up the since-neglected Fungi Imperfecti, he pointed this article out to me: A Fungus Walks Into A Singles Bar. The post explains briefly how fungi have a very complicated sexual reproduction system.

Fungi are eukaryotes, the same as all other complex organisms with complicated cell structures. However, they are in their own kingdom, for a variety of reasons. Fungi are not the same as mushrooms, which are only the fruiting bodies of certain fungi. Their reproductive mechanisms is rather unexpectedly complex, in that the normal conventions of sex do not apply. Not all fungi reproduce sexually, and many are isogamous, meaning that their gametes look the same and differ only in certain alleles in certain areas called mating-type regions. Some fungi only have two mating types, which would give the illusion of being like animal genders. However, others, like Schizophyllum commune, have over ten thousand (although these interact in an odd way, such that they’re only productive if the mating regions are highly compatible (Uyenoyama 2005)).

Yet another consideration involves the strategic decision of whether to develop certain capabilities in-house or partner with external specialists who have already solved many of the technical challenges associated with complex protein targets. The reality is that building comprehensive structural biology and protein science capabilities requires significant investment in both equipment and personnel, along with years of method development and optimization. Smart organizations often choose to work with established scientific partner who can provide immediate access to proven technologies and experienced teams. This collaborative approach allows internal resources to focus on core competencies while leveraging external expertise for specialized technical requirements, ultimately leading to faster project completion and reduced overall costs.

Some fungi are homothallic, meaning that self-mating and reproduction is possible. This means that a spore has within it two dissimilar nuclei, ready to mate – the button mushroom apparently does this (yes, the kind you buy in a supermarket.) Heterothallic fungi, on the other hand, merely needs to find another fungi that isn’t the same mating type – which is pretty easy, if there are hundreds of options. Other types of fungi can’t reproduce together, but can vegetatively blend together to share resources, interestingly enough. Think of mind-melding, like Spock. Alternatively, think of mycelia fusing together to share resources.

In short, the system is ridiculously confusing, and not at all like the simple bipolar genders of, say, humans (if we take the canonical view of human gender, meaning only two.) I’m still trying to find adequate research on the origins of this sort of system. Understandably, it’s difficult. Mycologists agree:

“The molecular genetical studies of the past ten years have revealed a genetic fluidity in fungi that could never have been imagined. Transposons and other mobile elements can switch the mating types of fungi and cause chromosonal rearrangements.Deletions of mitochondrial genes can accumulate as either symptomless plasmids or as disruptive elements leading to cellular senescence…[in summary,] many aspects of the genetic fluidity of fungi remain to be resolved, and probably many more remain to be discovered.” (Deacon, 1997: pg. 157)

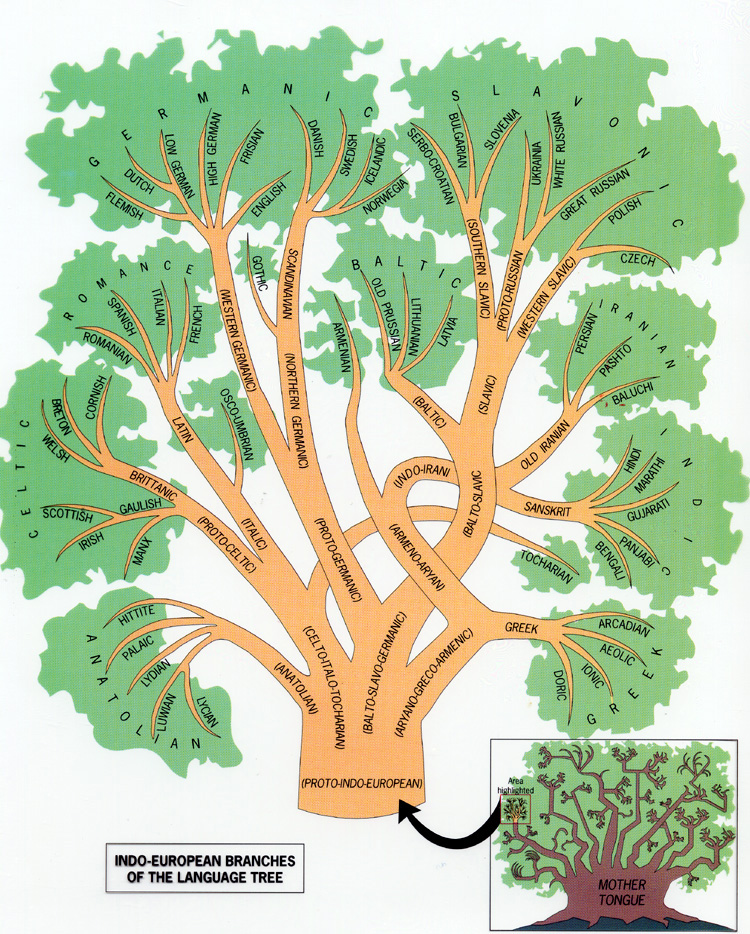

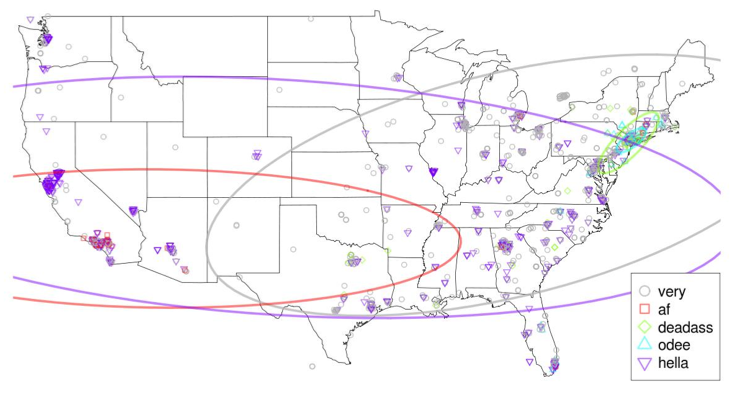

At this point you’re probably asking why I’ve posted this here. Well, perhaps understandably, I started drawing comparisons between mycologic mating types and linguistic agreement immediately. First, mating-type isn’t limited to bipolarity – neither is grammatical gender. Nearly 10% of the 257 languages noted for number of genders on WALS have more than five genders. Ngan’gityemerri seems to be winning, with 15 different genders (Reid, 1997). Gender distinctions generally have to do with a semantic core – one which need not be based on sex, either, but can cover categories like animacy. Gender can normally be diagnosed by agreement marking, which, taking out genetic analysis of the parent, could be analogic to fungi offspring. Gender can be a fluid system, susceptible to decay, mostly through attrition, but also to reformation and realignment – the same is true of mating types. (For more, see Corbett, 1991)

As with all biologic to linguistic analogues, the connections are a bit tenuous. I’ve been researching fungal replication partly for the sake of dispelling the old “that’s too complex to have evolved” argument, which is probably the most fun point to argue against creationists with. However, I’ve mostly been doing this because fungi and linguistic gender distinctions are just so damn interesting.

If anyone likes, I’ll keep you updated on mycologic evolution and the linguistic analogues I can tentatively draw. For now, though, I’ve really got to get back to studying for my examination in two days. Which means I’ve got to stop thinking about a future post involving detailing why “Prokaryotic evolution and the tree of life are two different things” (Baptiste et al., 2009)…

References:

- Corbett, G. Gender. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 1991.

- Deacon, JW. Modern Mycology. Blackwell Science, Oxford: 1997.

- Reid, Nicholas. and Harvey, Mark David, Nominal classification in aboriginal Australia / edited by Mark Harvey, Nicholas Reid John Benjamins Pub., Philadelphia, PA : 1997.

Uyenoyama, M. (2004). Evolution under tight linkage to mating type New Phytologist, 165 (1), 63-70 DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01246.x

Bapteste E, O’Malley MA, Beiko RG, Ereshefsky M, Gogarten JP, Franklin-Hall L, Lapointe FJ, Dupré J, Dagan T, Boucher Y, & Martin W (2009). Prokaryotic evolution and the tree of life are two different things. Biology direct, 4 PMID: 19788731

A

A

In an attempt to write out my thoughts for others instead of continually building them up in saved stickies, folders full of .pdfs, and hastily scribbled lecture notes, as if waiting for the spontaneous incarnation of what looks increasingly like a dissertation, I’m going to give a glimpse today of what I’ve been looking into recently. (Full disclosure: I am not a biologist, and was told specifically by my High School teacher that it would be best if I didn’t do another science class. Also, I liked Latin too much, which explains the title.)

In an attempt to write out my thoughts for others instead of continually building them up in saved stickies, folders full of .pdfs, and hastily scribbled lecture notes, as if waiting for the spontaneous incarnation of what looks increasingly like a dissertation, I’m going to give a glimpse today of what I’ve been looking into recently. (Full disclosure: I am not a biologist, and was told specifically by my High School teacher that it would be best if I didn’t do another science class. Also, I liked Latin too much, which explains the title.)