A recent study published in the proceedings of the Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing Conference (EMNLP) in October and presented in the LSA conference last week found evidence of geographical lexical variation in Twitter posts. (For news stories on it, see here and here.) Eisenstein, O’Connor, Smith and Xing took a batch of Twitter posts from a corpus released of 15% of all posts during a week in March. In total, they kept 4.7 million tokens from 380,000 messages by 9,500 users, all geotagged from within the continental US. They cut out messages from over-active users, taking only messages from users with less than a thousand followers and followees (However, the average author published around 40~ posts per day, which might be seen by some as excessive. They also only took messages from iPhones and BlackBerries, which have the geotagging function. Eventually, they ended up with just over 5,000 words, of which a quarter did not appear in the spell-checking lexicon aspell.

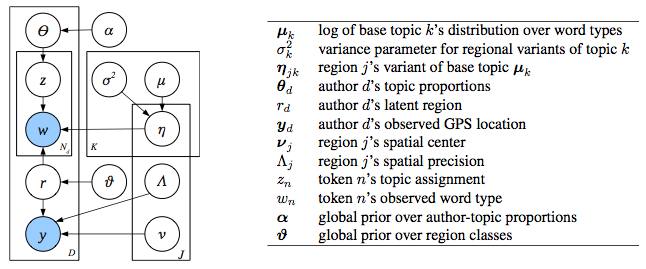

In order to figure out lexical variation accurately, both topic and geographical regions had to be ascertained. To do this, they used a generative model (seen above) that jointly figured these in. Generative models work on the assumption that text is the output of a stochastic process that can be analysed statistically. By looking at mass amounts of texts, they were able to infer the topics that are being talked about. Basically, I could be thinking of a few topics – dinner, food, eating out. If I am in SF, it is likely that I may end up using the word taco in my tweet, based on those topics. What the model does is take those topics and figure from them which words are chosen, while at the same time figuring in the spatial region of the author. This way, lexical variation is easier to place accurately, whereas before discourse topic would have significantly skewed the results (the median error drops from 650 to 500 km, which isn’t that bad, all in all.)

![]() The way it works (in summary and quoting the slide show presented at the LSA annual meeting, since I’m not entirely sure on the details) is that, in order to add a topic, several things must be done. For each author, the model a) picks a region from P( r | ∂ ) b) picks a location from P( y | lambda, v ) and c) picks a distribution over P( Theta | alpha ). For each token, it must a) pick a topic from P( z | Theta ), and then b) pick a word from P( w | nu ). Or something like that (sorry). For more, feel free to download the paper on Eisenstien’s website.

The way it works (in summary and quoting the slide show presented at the LSA annual meeting, since I’m not entirely sure on the details) is that, in order to add a topic, several things must be done. For each author, the model a) picks a region from P( r | ∂ ) b) picks a location from P( y | lambda, v ) and c) picks a distribution over P( Theta | alpha ). For each token, it must a) pick a topic from P( z | Theta ), and then b) pick a word from P( w | nu ). Or something like that (sorry). For more, feel free to download the paper on Eisenstien’s website.

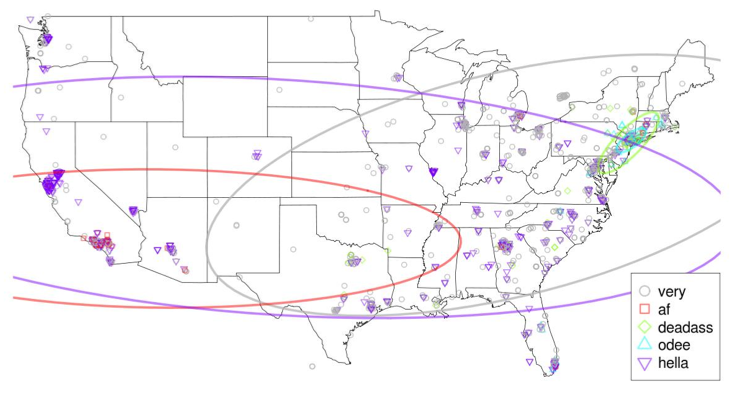

![]() Well, what did they find? Basically, Twitter posts do show massive variation based on region. There are geographically-specific proper names, of course, and topics of local prominence, like taco in LA and cab in NY. There’s also variation in foreign language words, with pues in LA but papi in SF. More interestingly, however, there is a major difference in regional slang. ‘uu’, for instance, is pretty much exclusively on the Eastern seaboard, while ‘you’ is stretched across the nation (with ‘yu’ being only slightly smaller.) ‘suttin’ for something is used only in NY, as is ‘deadass’ (meaning very) and, on and even smaller scale, ‘odee’, while ‘af’ is used for very in the Southwest, and ‘hella’ is used in most of the Western states.

Well, what did they find? Basically, Twitter posts do show massive variation based on region. There are geographically-specific proper names, of course, and topics of local prominence, like taco in LA and cab in NY. There’s also variation in foreign language words, with pues in LA but papi in SF. More interestingly, however, there is a major difference in regional slang. ‘uu’, for instance, is pretty much exclusively on the Eastern seaboard, while ‘you’ is stretched across the nation (with ‘yu’ being only slightly smaller.) ‘suttin’ for something is used only in NY, as is ‘deadass’ (meaning very) and, on and even smaller scale, ‘odee’, while ‘af’ is used for very in the Southwest, and ‘hella’ is used in most of the Western states.

More importantly, though, the study shows that we can separate geographical and topical variation, as well as discover geographical variation from text instead of relying solely on geotagging, using this model. Future work from the authors is hoped to cover differences between spoken variation and variation in digital media. And I, for one, think that’s #deadass cool.

Jacob Eisenstein, Brendan O’Connor, Noah A. Smith, & Eric P. Xing (2010). A Latent Variable Model for Geographic Lexical Variation. Proceedings of EMNLP