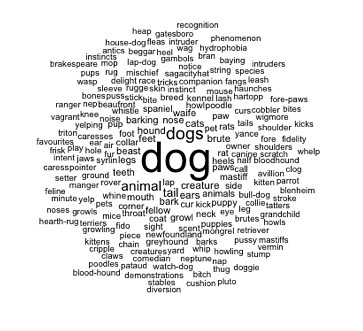

I’ve decided that it is time for some new terms. I’ve been using “meme” as the cultural analog for the biological “gene”, which is more or less the use that Dawkins had in mind when he coined the term. But I’ve decided to scrap it. I also need a term for the cultural analog to the biological phenotype.

From “meme” to “coordinator”

The problem with “meme” as a term is that it has accumulated quite a bit of conceptual baggage. None of that baggage is compatible with my sense of how the cultural analogue to genes function, and much of it is harmful nonsense. Oh, as a popular term as in “internet meme” it’s fine and, in any event, it would be foolish of me to try to interfere with that. The trouble comes when you try to use more or less that meaning in a serious investigation into culture. No one has yet made it work.

I’ve expressed my views in a long series article, book chapters, posts and working papers going back almost two decades. Here’s my most recent thinking:

- Cultural Evolution, Memes, and the Trouble with Dan Dennett (working paper)

- Memes as Data: Targets, Couplers, and Designators (post)

- Cultural Evolution: Some Terminology (post)

If I jettison “meme”, however, what’s the alternative?

I don’t like coining new words so I’d like to use an existing word. I’ve decided up “coordinator,” which expresses nicely the function that these entities have to performer. The cultural analog to the gene coordinates the minds of people during interaction, whether face-to-face or through various media. This is not the place to explain that – you can find plenty of explanatory material in the above-linked documents, and others as well. I note only that the term sidesteps the notion of bits of “information” that get passed from person to person, brain to brain. On the contrary, it helps explain how we can, in effect, walk about in one another’s minds (cf. Peter Gärdenfors, The Geometry of Meaning, 2014 chapters four and five).

From “ideotype” to “phantasm”

What about the analogue to the biological phenotype, the individual organism in its environment? Ever since I first thought about cultural evolution as a process of “blind variation and selective retention” (in Donald Campbell’s formulation) I figured that the selecting was being done by groups of human beings and therefore that the environment of cultural evolutionary adaptedness had to be something like a “group mind.” In some way, what was being selected had to be public. I first articulated that position in an article I published in 1996, Culture as an Evolutionary Arena (Journal of Social and Biological Structures). But it took several years before I arrived at a satisfactory, albeit still provisional, formulation. Continue reading “Terminology for Cultural Evolution: Coordinators and Phantasms”