The last few posts have showed that several domains of constraint influence colour categorisation. There is evidence that these categorisations can influence perception, which has been identified as a crucial argument for Relativism. This section considers the Cultural implication, summarised in the last section, in greater depth. First, the idea of perceptual warping is explained and applied to colour categorisation. Next, the impact of a feedback loop caused by an Embodied approach is discussed in terms of Niche Construction. Thirdly, perceptual warping, within a system with Niche Construction dynamics is argued to lead to convergence of perceptual spaces, resulting in better communication. Finally, a note is made on compositionality in language. It is concluded that Embodied Cognition may explain some of the features of the emergence of language.

Perceptual Spaces

This section explains perceptual warping. Many models of the cultural transmission of denotation systems begin by defining a perceptual space for each individual which is then divided up with loci and boundaries (e.g., deBoer, 1999). Eventually, a kind of ‘lookup table’ is produced where an individual calculates within which boundary a given stimulus falls in order to classify it. An alternate view would be that each individual alters (warps) the perceptual space to suit the categories (Goldstone, 1994; Kuhl, 1994). This is not a controversial theory for the auditory modality. For instance, although born with the ability to detect any meaningful difference in any language, children eventually become unable to detect those differences that do not exist in the languages spoken around them (Eimas, 1978, Miyawaki, 1975, Kuhl, 1983). In other words, humans do not merely categorise areas of the audible spectrum as belonging to particular phonemes, but actually alter their perceptual space to suit the phonemic system. In the visual domain, Kuhl (1994) argues that the perceptual space is permanently changed by exposure to graphemes, although Lupyan (2008) shows that categorical perception can emerge on-line.

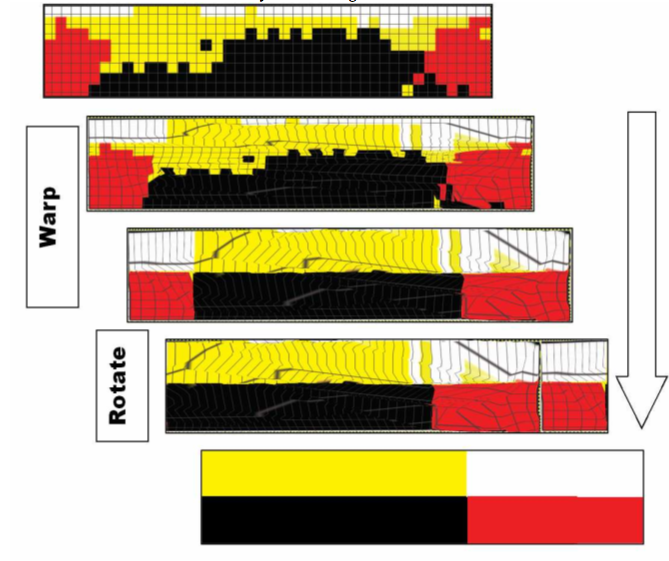

The figure above is a graphical illustration of warping a perceptual space (Colour space of Culina, from Regier, Kay & Khertarpal, 2007, p. 1439). The division of the Munsell colour space by speakers of Culina is warped and rotated to optimally encode the colour categories. Formally, the parameterisations are the same. However, warping the perceptual space allows for compression of information. For example, the initial encoding of the Figure takes up to 40 x 8 units, while the final encoding takes only 4 units . This can ease processing and storage requirements. Compression reduces the uncertainty between categories (e.g., red vs. green) and the ability for individuals to differentiate within categories (e.g., different shades of red), similar to the effects of categorical perception.

This approach has already been suggested. Buchsbaum and Bloch’s (2002) study showed that the NMF algorithm approximates colour categorisation in real languages (Non-negative Matrix Factorisation – a factor analysis algorithm like PCA, except that it is designed for values that are inherently positive and cannot be centred). NMF essentially warps the perceptual space to best describe its limits. The current study suggests that language sets constraints on an NMF-like process which works to alter the perceptual space to suit culturally salient colour contrasts. However, it is suggested that this optimisation is not primarily a response to an adaptive pressure, but a consequence of the way we understand language. Indeed, it is only because our perceptions can be aligned with our language system that semantics works at all. This would fit better with an Embodied view than a Symbolist view.

However, humans are able to perceive gradients in colours within categories. There are two explanations for this. Firstly, there may be two separate, competing perceptual and ‘categorical’ colour spaces, similar to Connell and Lynott’s (2009) hypothesis. Since the categorical system is shared and can quickly adapt to immediate environmental pressures, one would expect agents with two systems to increasingly rely on the categorical system, especially for communication (see code duality theory, e.g., Hoffmeyer & Emmeche, 1991). In contrast, novel tasks which involved no communication (e.g., comparing colours and choosing an ‘odd one out’) may rely more on the true perceptual system. A second explanation for the flexibility of categories is suggested by Lupyan (2008) who shows that perceptual spaces can be warped, but by context-specific, online processes rather than long-term, memory-based processes. This would allow a single conceptual/perceptual system (as Embodied Cognition hypothesises), as well as explaining the plasticity of language.

Next, a look at how Embodied Cognition fits into this picture ->

DEBOER, B. (2000). Self-organization in vowel systems Journal of Phonetics, 28 (4), 441-465 DOI: 10.1006/jpho.2000.0125

Goldstone, R. (1994). Influences of categorization on perceptual discrimination. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 123 (2), 178-200 DOI: 10.1037//0096-3445.123.2.178

Kuhl, P. (1994). Learning and representation in speech and language Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 4 (6), 812-822 DOI: 10.1016/0959-4388(94)90128-7

Miyawaki, K., Strange, W., Verbrugge, R. R., Liberman, A. M., Jenkins, J. J., & Fujimura, O. (1975). An effect of linguistic experience: The discrimination of (r) and (l) by native speakers of Japanese and

English

Perception and Psychophysics, 18, 331-340

KUHL, P. (1983). Perception of auditory equivalence classes for speech in early infancy Infant Behavior and Development, 6 (2-3), 263-285 DOI: 10.1016/S0163-6383(83)80036-8

Lupyan G (2008). From chair to “chair”: a representational shift account of object labeling effects on memory. Journal of experimental psychology. General, 137 (2), 348-69 PMID: 18473663

Buchsbaum, G. (2002). Color categories revealed by non-negative matrix factorization of Munsell color spectra Vision Research, 42 (5), 559-563 DOI: 10.1016/S0042-6989(01)00303-0

Connell, L., & Lynott, D. (2009). Is a bear white in the woods? Parallel representation of implied object color during language comprehension Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16 (3), 573-577 DOI: 10.3758/PBR.16.3.573