A new book is to be published on May the 24th. By John F. Hoffecker the book is entitled “Landscape of the Mind: Human Evolution and the Archaeology of Thought” – it aims to look at the emergence of human thought and language through archaeological evidence

A new book is to be published on May the 24th. By John F. Hoffecker the book is entitled “Landscape of the Mind: Human Evolution and the Archaeology of Thought” – it aims to look at the emergence of human thought and language through archaeological evidence

Archeologists often struggle to find fossil evidence pertaining to the evolution of the brain. Thoughts are a hard thing to fossilize. However, John Hoffecker claims that this is not the case and fossils and archaeological evidence for the evolution of the human mind are abundant.

Hoffecker has developed a concept which he calls the “super-brain” which he hypothesises emerged in Africa some 75,000 years ago. He claims that human’s ability to share thoughts between individuals is analogous to the abilities of honey bees who are able to communicate the location of food both in terms of distance and direction. They do this using a waggle-dance. Humans are able to share thoughts between brains using communicative methods, the most obvious of these being language.

Fossil evidence for the emergence of speech is thin on the ground and, where it does exist, is quite controversial. However, symbols emerging in the archaeological record coincides with an increase in evidence of creativity being displayed in many artifacts from the same time. Creative, artistic designs scratched on mineral pigment show up in Africa about 75,000 years ago and are thought to be evidence for symbolism and language

Hoffecker also hypothesises that his concept of the super-brain is likely to be connected to things like bipedalism and tool making. He claims that it was tool making which helped early humans first develop the ability to represent complex thoughts to others.

He claims that tools were a consequence of bipedalism as this freed up the hands to make and use tools. Hoffecker pin points his “super-brain” as beginning to emerge 1.6 million years ago when the first hand axes began to appear in the fossil record. This is because hand axes are thought to be an external realisation of human thought as they bear little resemblance to the natural objects they were made from.

By 75,00 years ago humans were producing perforated shell ornaments, polished bone awls and simple geometric designs incised into lumps of red ochre.

Humans are known to have emerged from Africa between 60,00 to 50,000 years ago based on archeological evidence. Hoeffecker hypothesises that – “Since all languages have basically the same structure, it is inconceivable to me that they could have evolved independently at different times and places.”

Hoeffecker also lead a study in 2007 that discovered a carved piece of mammoth ivory that appears to be the head of a small figurine dating to more than 40,000 years ago. This is claimed to be the oldest piece of figurative art ever discovered. Finds like this illustrate the creative mind of humans as they spread out of Africa.

Figurative art and musical instruments which date back to before 30,000 years ago have also been discovered in caves in France and Germany.

This looks to be nothing new but archaeological evidence is something which a lot of people interested in language evolution do not often discuss. I also don’t really know what to think of Hoeffecker’s claim that “all languages basically have the same structure”. What do you think?

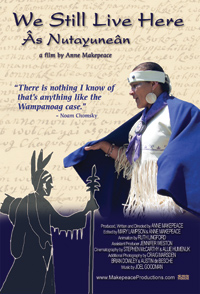

The story begins in 1994 when Jessie Little Doe, an intrepid, thirty-something Wampanoag social worker, began having recurring dreams: familiar-looking people from another time addressing her in an incomprehensible language. Jessie was perplexed and a little annoyed– why couldn’t they speak English? Later, she realized they were speaking Wampanoag, a language no one had used for more than a century. These events

The story begins in 1994 when Jessie Little Doe, an intrepid, thirty-something Wampanoag social worker, began having recurring dreams: familiar-looking people from another time addressing her in an incomprehensible language. Jessie was perplexed and a little annoyed– why couldn’t they speak English? Later, she realized they were speaking Wampanoag, a language no one had used for more than a century. These events New footage has been filmed of a little known animal called the Streaked Tenrec in Madagascar. The footage shows the creatures can rub their quills together to make ultrasound calls and can also produce tongue clicks to each other which are outside of the range of human hearing. Because of the ultra sonic nature of these sounds, it has been unknown quite to the extent that these creatures can do this, before now.

New footage has been filmed of a little known animal called the Streaked Tenrec in Madagascar. The footage shows the creatures can rub their quills together to make ultrasound calls and can also produce tongue clicks to each other which are outside of the range of human hearing. Because of the ultra sonic nature of these sounds, it has been unknown quite to the extent that these creatures can do this, before now.