Shigeru Miyagawa, Shiro Ojima, Robert Berwick and Kazuo Okanoya have recently published a new paper in Frontiers in Psychology, which can be seen as a follow-up to the 2013 Frontiers paper by Miyagawa, Berwick and Okanoya (see Hannah’s post on this paper). While the earlier paper introduced what they call the “Integration Hypothesis of Human Language Evolution”, the follow-up paper seeks to provide empirical evidence for this theory and discusses potential challenges to the Integration Hypothesis.

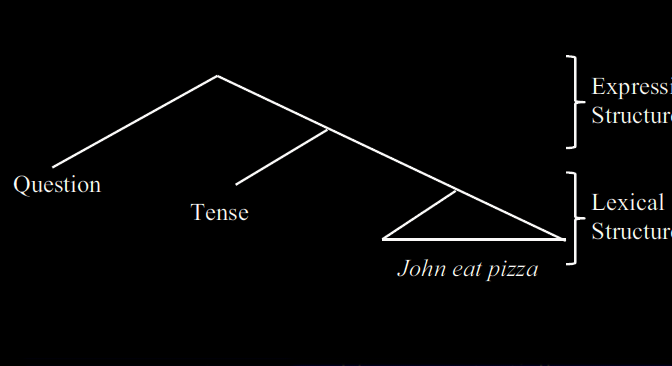

The basic idea of the Integration Hypothesis, in a nutshell, is this: “All human language sentences are composed of two meaning layers” (Miyagawa et al. 2013: 2), namely “E” (for “expressive”) and “L” (for “lexical”). For example, sentences like “John eats a pizza”, “John ate a pizza”, and “Did John eat a pizza?” are supposed to have the same lexical meaning, but they vary in their expressive meaning. Miyagawa et al. point to some parallels between expressive structure and birdsong on the one hand and lexical structure and the alarm calls of non-human primates on the other. More specifically, “birdsongs have syntax without meaning” (Miyagawa et al. 2014: 2), whereas alarm calls consist of “isolated uttered units that correlate with real-world references” (ibid.). Importantly, however, even in human language, the Expression Structure (ES) only admits one layer of hierarchical structure, while the Lexical Structure (LS) does not admit any hierarchical structure at all (Miyagawa et al. 2013: 4). The unbounded hierarchical structure of human language (“discrete infinity”) comes about through recursive combination of both types of structure.

This is an interesting hypothesis (“interesting” being a convenient euphemism for “well, perhaps not that interesting after all”). Let’s have a closer look at the evidence brought forward for this theory.

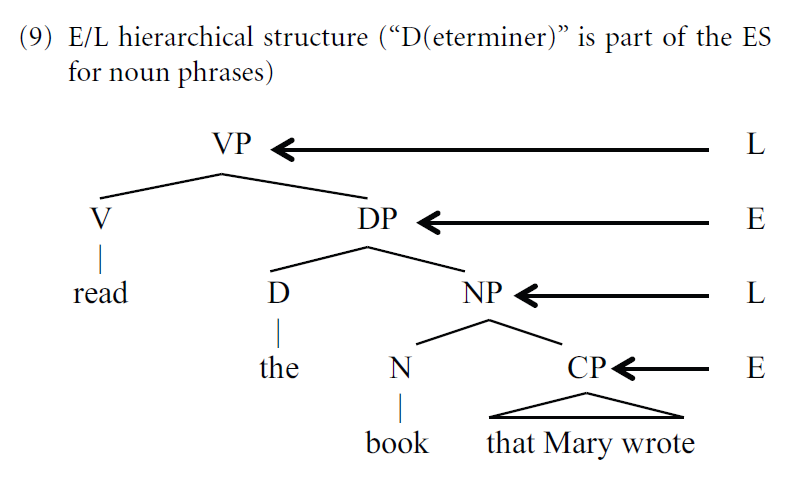

Miyagawa et al. “focus on the structures found in human language” (Miyagawa et al. 2014: 1), particularly emphasizing the syntactic structure of sentences and the internal structure of words. In a sentence like “Did John eat pasta?”, the lexical items John, eat, and pasta constitute the LS, while the auxiliary do, being a functional element, is seen as belonging to the expressive layer. In a more complex sentence like “John read the book that Mary wrote”, the VP and NP notes are allocated to the lexical layer, while the DP and CP nodes are allocated to the expressive layer.

As pointed out above, LS elements cannot directly combine with each other according to Miyagawa et al. (the ungrammaticality of e.g. John book and want eat pizza is taken as evidence for this), while ES is restricted to one layer of hierarchical structure. Discrete infinity then arises through recursive application of two rules:

(i) EP → E LP

(ii) LP → L EP

Rule (i) states that the E category can combine with LP to form an E-level structure. Rule (ii) states that the L category can combine with an E-level structure to form an L-level structure. Together, these two rules suffice to yield arbitrarily deep hierarchical structures.

The alternation between lexical and expressive elements, as exemplified in Figure (3) from the 2014 paper (= Figure 9 from the 2013 paper, reproduced above), is thus essential to their theory since they argue that “inside E and L we only find finite-state processes” (Miyagawa et al. 2014: 3). Several phenomena, most notably Agreement and Movement, are explained as “linking elements” between lexical and functional heads (cf. also Miyagawa 2010). A large proportion of the 2014 paper is therefore dedicated to phenomena that seem to argue against this hypothesis.

For example, word-formation patterns that can be applied recursively seem to provide a challenge for the theory, cf. example (4) in the 2014 paper:

(4) a. [anti-missile]

b. [anti-[anti-missile]missile] missileThe ostensible point is that this formation can involve center embedding, which would constitute a non-finite state construction.

However, they propose a different explanation:

When anti– combines with a noun such as missile, the sequence anti-missile is a modifier that would modify a noun with this property, thus, [anti-missile]-missile, [anti-missile]-defense. Each successive expansion forms via strict adjacency, (…) without the need to posit a center embedding, non-regular grammar.

Similarly, reduplication is re-interpreted as a finite state process. Furthermore, they discuss N+N compounds, which seems to violate “the assumption that L items cannot combine directly — any combination requires intervention from E.” However, they argue that the existence of linking elements in some languages provides evidence “that some E element does occur between the two L’s”. Their example is German Blume-n-wiese ‘flower meadow’, others include Freundeskreis ‘circle of friends’ or Schweinshaxe ‘pork knuckle’. It is commonly assumed that linking elements arose from grammatical markers such as genitive -s, e.g. Königswürde ‘royal dignity’ (from des Königs Würde ‘the king’s dignity’). In this example, the origin of the linking element is still transparent. The -es- in Freundeskreis, by contrast, is an example of a so-called unparadigmatic linking element since it literally translates to ‘circle of a friend’. In this case as well as in many others, the linking element cannot be traced back directly to a grammatical affix. Instead, it seems plausible to assume that the former inflectional suffix was reanalyzed as a linking element from the paradigmatic cases and subsequently used in other compounds as well.

To be sure, the historical genesis of German linking elements doesn’t shed much light on their function in present-day German, which is subject to considerable debate. Keeping in mind that these items evolved gradually however raises the question how the E and L layers of compounds were linked in earlier stages of German (or any other language that has linking elements). In addition, there are many German compounds without a linking element, and in other languages such as English, “linked” compounds like craft-s-man are the exception rather than the rule. Miyagawa et al.’s solution seems a bit too easy to me: “In the case of teacup, where there is no overt linker, we surmise that a phonologically null element occurs in that position.”

As an empiricist, I am of course very skeptical towards any kind of null element. One could possibly rescue their argument by adopting concepts from Construction Grammar and assigning E status to the morphological schema [N+N], regardless of the presence or absence of a linking element, but then again, from a Construction Grammar point of view, assuming a fundamental dichotomy between E and L structures doesn’t make much sense in the first place. That said, I must concede that the E vs. L distinction reflects basic properties of language that play a role in any linguistic theory, but especially in Construction Grammar and in Cognitive Linguistics. On the one hand, it reflects the rough distinction between “open-class” and “closed-class” items, which plays a key role in Talmy’s (2000) Cognitive Semantics and in the grammaticalization literature (cf. e.g. Hopper & Traugott 2003). As many grammaticalization studies have shown, most if not all closed-class items are “fossils” of open-class items. The abstract concepts they encode (e.g. tense or modality) are highly relevant to our everyday experience and, consequently, to our communication, which is why they got grammaticized in the first place. As Rose (1973: 516) put it, there is no need for a word-formation affix deriving denominal verbs meaning “grasp NOUN in the left hand and shake vigorously while standing on the right foot in a 2 ½ gallon galvanized pail of corn-meal-mush”. But again, being aware of the historical emergence of these elements begs the question if a principled distinction between the meanings of open-class vs. closed-class elements is warranted.

On the other hand, the E vs. L distinction captures the fundamental insight that languages pair form with meaning. Although they are explicitly talking about the “duality of semantics“, Miyagawa et al. frequently allude to formal properties of language, e.g. by linking up syntactic strutures with the E layer:

The expression layer is similar to birdsongs; birdsongs have specific patterns, but they do not contain words, so that birdsongs have syntax without meaning (Berwick et al., 2012), thus it is of the E type.

While the “expression” layer thus seems to account for syntactic and morphological structures, which are traditionally regarded as purely “formal” and meaningless, the “lexical” layer captures the referential function of linguistic units, i.e. their “meaning”. But what is meaning, actually? The LS as conceptualized by Miyagawa et al. only covers the truth-conditional meaning of sentences, or their “conceptual content”, as Langacker (2008) calls it. From a usage-based perspective, however, “an expression’s meaning consists of more than conceptual content – equally important to linguistic semantics is how that content is shaped and construed.” (Langacker 2002: xv) According to the Integration Hypothesis, this “construal” aspect is taken care of by closed-class items belonging to the E layer. However, the division of labor envisaged here seems highly idealized. For example, tense and modality can be expressed using open-class (lexical) items and/or relying on contextual inference, e.g. German Ich gehe morgen ins Kino ‘I go to the cinema tomorrow’.

It is a truism that languages are inherently dynamic, exhibiting a great deal of synchronic variation and diachronic change. Given this dynamicity, it seems hard to defend the hypothesis that a fundamental distinction between E and L structures which cannot combine directly can be found universally in the languages of the world (which is what Miyagawa et al. presuppose). We have already seen that in the case of compounds, Miyagawa et al. have to resort to null elements in order to uphold their hypothesis. Furthermore, it seems highly likely that some of the “impossible lexical structures” mentioned as evidence for the non-combinability hypothesis are grammatical at least in some creole languages (e.g. John book, want eat pizza).

In addition, it seems somewhat odd that E- and L-level structures as “relics” of evolutionarily earlier forms of communication are sought (and expected to be found) in present-day languages, which have been subject to millennia of development. This wouldn’t be a problem if the authors were not dealing with meaning, which is not only particularly prone to change and variation, but also highly flexible and context-dependent. But even if we assume that the existence of E-layer elements such as affixes and other closed-class items draws on innate dispositions, it seems highly speculative to link the E layer with birdsong and the L layer with primate calls on semantic grounds.

The idea that human language combines features of birdsong with features of primate alarm calls is certainly not too far-fetched, but the way this hypothesis is defended in the two papers discussed here seems strangely halfhearted and, all in all, quite unconvincing. What is announced as “providing empirical evidence” turns out to be a mostly introspective discussion of made-up English example sentences, and if the English examples aren’t convincing enough, the next best language (e.g. German) is consulted. (To be fair, in his monograph, Miyagawa (2010) takes a broader variety of languages into account.) In addition, much of the discussion is purely theory-internal and thus reminiscent of what James has so appropriately called “Procrustean Linguistics“.

To their credit, Miyagawa et al. do not rely exclusively on theory-driven analyses of made-up sentences but also take some comparative and neurological studies into account. Thus, the Integration Hypothesis – quite unlike the “Mystery” paper (Hauser et al. 2014) co-authored by Berwick and published in, you guessed it, Frontiers in Psychology (and insightfully discussed by Sean) – might be seen as a tentative step towards bridging the gap pointed out by Sverker Johansson in his contribution to the “Perspectives on Evolang” section in this year’s Evolang proceedings:

A deeper divide has been lurking for some years, and surfaced in earnest in Kyoto 2012: that between Chomskyan biolinguistics and everybody else. For many years, Chomsky totally dismissed evolutionary linguistics. But in the past decade, Chomsky and his friends have built a parallel effort at elucidating the origins of language under the label ‘biolinguistics’, without really connecting with mainstream Evolang, either intellectually or culturally. We have here a Kuhnian incommensurability problem, with contradictory views of the nature of language.

On the other hand, one could also see the Integration Hypothesis as deepening the gap since it entirely draws on generative (or “biolinguistic”) preassumptions about the nature of language which are not backed by independent empirical evidence. Therefore, to conclusively support the Integration Hypothesis, much more evidence from many different fields would be necessary, and the theoretical preassumptions it draws on would have to be scrutinized on empirical grounds, as well.

References

Hauser, Marc D.; Yang, Charles; Berwick, Robert C.; Tattersall, Ian; Ryan, Michael J.; Watumull, Jeffrey; Chomsky, Noam; Lewontin, Richard C. (2014): The Mystery of Language Evolution. In: Frontiers in Psychology 4. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00401

Hopper, Paul J.; Traugott, Elizabeth Closs (2003): Grammaticalization. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johansson, Sverker: Perspectives on Evolang. In: Cartmill, Erica A.; Roberts, Séan; Lyn, Heidi; Cornish, Hannah (eds.) (2014): The Evolution of Language. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference. Singapore: World Scientific, 14.

Langacker, Ronald W. (2002): Concept, Image, and Symbol. The Cognitive Basis of Grammar. 2nd ed. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter (Cognitive Linguistics Research, 1).

Langacker, Ronald W. (2008): Cognitive Grammar. A Basic Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Miyagawa, Shigeru (2010): Why Agree? Why Move? Unifying Agreement-Based and Discourse-Configurational Languages. Cambridge: MIT Press (Linguistic Inquiry, Monographs, 54).

Miyagawa, Shigeru; Berwick, Robert C.; Okanoya, Kazuo (2013): The Emergence of Hierarchical Structure in Human Language. In: Frontiers in Psychology 4. doi 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00071

Miyagawa, Shigeru; Ojima, Shiro; Berwick, Robert C.; Okanoya, Kazuo (2014): The Integration Hypothesis of Human Language Evolution and the Nature of Contemporary Languages. In: Frontiers in Psychology 5. doi 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00564

Rose, James H. (1973): Principled Limitations on Productivity in Denominal Verbs. In: Foundations of Language 10, 509–526.

Talmy, Leonard (2000): Toward a Cognitive Semantics. 2 vol. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

P.S.: After writing three posts in a row in which I critizised all kinds of studies and papers, I herby promise that in my next post, I will thoroughly recommend a book and return to a question raised only in passing in this post. [*suspenseful cliffhanger music*]

Thanks for the interesting commentary. I’d be cautious about equating ‘generative’ theories of linguistics (which includes, amongst others, HPSG, LFG, GPSG and Minimalism), and biolinguistics. The stuff done under the rubrik of generative linguistics is largely independent of the question of how language evolved (i guess you could characterise it as specifying the phenotype).

I doubt that lexical and expressive layers may be separated. I find that many lexical items have emotional overtones, many word are charged. On the other hand I do not think that that the concept of meaning as used above is correct either.

Thanks Patrick – of course you’re right, not all of generative research is biolinguistics, and not all studies that go under the label of “biolinguistics” are generatively-oriented (in fact, Tom Givón of all people has called one of his books “Bio-linguistics”). My criticism was only geared towards the shared assumptions of what one might call the core group of generative biolinguists, and it shouldn’t be taken to extend to other approaches in generative linguistics and/or biolinguistics, which are quite insightful at times, although I don’t always agree with their conclusions.