A new paper has just appeared in the proceedings of the royal society B entitled, “Language evolution: syntax before phonology?” by Collier et al.

The abstract is here:

Phonology and syntax represent two layers of sound combination central to language’s expressive power. Comparative animal studies represent one approach to understand the origins of these combinatorial layers. Traditionally, phonology, where meaningless sounds form words, has been considered a simpler combination than syntax, and thus should be more common in animals. A linguistically informed review of animal call sequences demonstrates that phonology in animal vocal systems is rare, whereas syntax is more widespread. In the light of this and the absence of phonology in some languages, we hypothesize that syntax, present in all languages, evolved before phonology.

This is essentially a paper about the distinction between combinatorial and compositional structure and the emergence narrative of duality of patterning. I wrote a post about this a few months ago, see here. The paper focusses on evidence from non-human animals and also evidence from human languages, including Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language, looking at differences and similarities between human abilities and those of other animals.

Peter Marler outlined different types of call combinations found in animal communication by making a distinction between ‘Phonological syntax’ (combinatorial structure), which he claims is widespread in animals, and ‘lexical syntax’ (compositional structure), which he claims have yet to be described in animals (I can’t find a copy of the 1998 paper which Collier et al. cite, but he talks about this on his homepage here). Collier et al. however, disagree and review several animal communication systems which they claim fall under a definition of “lexical syntax”.

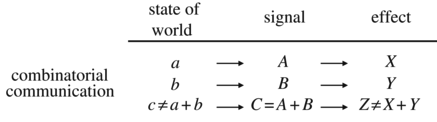

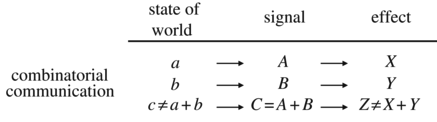

They start by defining what they mean by the different levels of structure within language (I talk about this here). They present the following relatively uncontroversial table:

Evidence from non-human species

The paper reviews evidence from 4 species; 1) Winter wrens (though you could arguably lump all birdsong in with their analysis for this one), 2) Campbell monkeys, 3) Putty-nosed monkeys and 4) Banded mongooses.

1) Birdsong is argued to be combinatorial, as whatever the combination of notes or syllables, the songs always have the same purpose and so the “meaning” can not be argued to be a result of the combination.

2) In contrast to Marler, the authors argue that Campbell monkeys have compositional structure in their calls. The monkeys give a ‘krak’ call when there is a leopard near, and a ‘hok’ call when there is an eagle. Interestingly, they can add an ‘-oo’ to either of these calls change their meanings. ‘Krak-oo’ denotes any general disturbance and ‘hok-oo’ denotes a disturbance in the canopy. One can argue then that this “-oo” has the same meaning of “disturbance”, no matter what construction it is in, and “hok” generally means “above”, hinting at compositional structure.

3) The authors also discuss Putty-nosed monkeys, which were also discussed in this paper by Scott-Philips and Blythe (again, discussed here). While Scott-Philips and Blythe arrive at the conclusion that the calls of putty-nosed monkeys are combinatorial (i.e. the combined effect of two signals does not amount to the combined meaning of those two signals):

“Applied to the putty-nosed monkey system, the symbols in this figure are: a, presence of eagles; b, presence of leopards; c, absence of food; A, ‘pyow’; B, ‘hack’ call; C = A + B ‘pyow–hack’; X, climb down; Y, climb up; Z ≠ X + Y, move to a new location. Combinatorial communication is rare in nature: many systems have a signal C = A + B with an effect Z = X + Y; very few have a signal C = A + B with an effect Z ≠ X + Y.”

However, Collier et al. argue this example is not necessarily combinatorial, as the pyow-hack sequences could be interpreted as idiomatic, or have much more abstract meanings such as ‘move-on-ground’ and ‘move-in-air’, however in order for this analysis to hold weight, one must assume the monkeys are able to use contextual information to make inferences about meaning, which is a pretty controversial claim. However, Collier et al. argue that it shouldn’t be considered so far-fetched given the presence of compositionality in the calls of Campbell monkeys.

4) The author’s also discuss Branded Mongooses who emit close calls while looking for food. Their calls begin with an initial noisy segment that encodes the caller’s identity, which is stable across all contexts. In searching and moving contexts, there is a second tonal harmonic that varies in length consistently with context. So one could argue that identity and context are being systematically encoded into their call sequences with one to one mappings between signal and meaning.

(One can’t help but think that a discussion of the possibility of compositionality in bee dances is a missed opportunity here.)

Syntax before phonology?

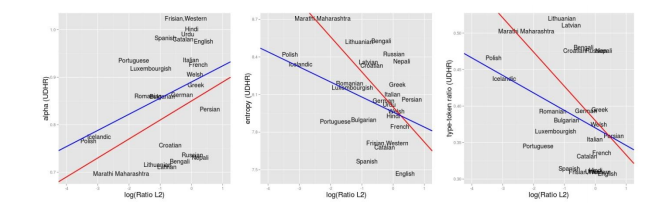

The authors use the above (very sketchy and controversial) examples of compositional structure to make the case that syntax came before phonology. Indeed, there exist languages where a level of phonological patterning does not exist (the go-to example being Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language). However, I would argue that the emergence of combinatoriality is, in large part, the result of the modality one is using to produce language. My current work is looking at how the size and dimensionality of a signal space, as well as how mappable that signal space is to a meaning space (to enable iconicity), can massively effect the emergence of a combinatorial system, and I don’t think it’s crazy to suggest the modality used will effect the emergence narrative for duality of patterning.

Collier et al. attempt to use some evidence from spoken languages with large inventories, or instances where single phonemes in spoken languages are highly context-dependant meaningful elements, to back up a story where syntax might have come first in spoken language. But given the physical and perceptual constraints of a spoken system, it’s really hard for me to imagine how a productive syntactic system could have existed without a level of phonological patterning. The paper makes the point that it is theoretically possible (which is really interesting), but I’m not convinced that it is likely (though this paper by Juliette Blevins is well worth a read).

Whilst I don’t disagree with Collier et al.’s conclusion that phonological patterning is most likely the product of cultural evolution, I feel like the physical constraints of a linguistic modality will massively effect the emergence of such a system, and arguing for an over-arching emergence story without consideration for non-cognitive factors is an over-sight.

References

Collier, K., Bickel, B., van Schaik, C., Manser, M., & Townsend, S. (2014). Language evolution: syntax before phonology? Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281 (1788), 20140263-20140263 DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2014.0263

AUTHOR: Denis Bouchard

AUTHOR: Denis Bouchard