Following some great work over at FeministPhilosophers to raise awareness of the prevalence of all-male conference events in Philosophy, an interdisciplinary action for gender equity at scholarly conferences has been doing the rounds over the last four days. It was proposed by Dan Sperber and Virginia Valian, who have also compiled an accompanying Q & A that is very informative indeed, especially for those who may not have thought about such issues before. The sentiment of this action is certainly commendable and it’s heartening to see this conversation being opened in the research community. In the spirit of continuing this conversation, I have made critical comments elsewhere that I’m more or less cross-posting here.

The commitment is summarised thus:

Commitment to gender equity at scholarly conferences Across the disciplines, disproportionately more men than women participate in scholarly conferences – as keynote or plenary speakers, as symposiasts, or as panelists. This, we believe, is the outcome of widespread and generally unintended bias. It is unfair, it hinders advancement in scholarship, and it is especially discouraging to junior scholars. Overcoming such bias involves not just awareness but positive action.We therefore undertake to make our participation in conferences – whether as an organizer, sponsor, or invited speaker – conditional on the invitation of women and men speakers in a fair and balanced manner.

So, we can understand this action as a distributed boycott of conferences that individuals believe have been unfair in their approach to inviting female speakers. There is a guideline in the accompanying Q & A on how signees can establish whether a conference has been organised fairly, which outlines various considerations you can make as an attendee and also as an organiser. The problem is that there is little to compel anyone signing this to actually make good on conditional conference participation, particularly since the bias is (as noted in the Q & A) unintended and unconscious even among those who personally endeavour to act against it. The consequences of public accountability are at best unclear, unless those signing up are also committing themselves to monitor the conduct of their fellow signatories. The fact that people generally have these sentiments before they’ve signed the commitment, and that simply holding this sentiment doesn’t seem to have made any difference to how conferences are organised, ought to make us pause.

This may seem a little unfair of me, but at least part of my cynicism is based on the fact that female representation in political parties and government positions is notoriously difficult to improve with non-binding good intentions alone. At Edinburgh University’s inaugural Chrystal Macmillan lecture last year Prof Pippa Norris showed that even voluntarily enacting quotas for a minimum number of female representatives was not enough to improve equity in political parties and make sure that they actually do anything. The only measure that proves effective is an additional penalty of non-registration for those parties that do not meet requirements. This is the case worldwide.

χ² = 28.071, d.f. = 1, p = < 0.0001

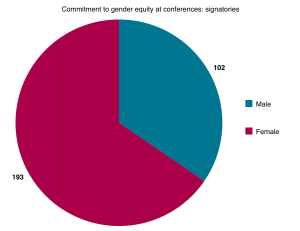

Related to the problems inherent in grassroots strategies of action, I also find myself wondering how it could benefit female scholars (individually but also at large), to make such a commitment. Surely the point here is that their representation is already under par. This is an especially important concern when we ask ourselves who is more likely to actually participate in such an action; despite the fact that this commitment is intended for everyone, I suspected that the one area where women might be overrepresented is on the signature list. As of today, this is certainly true (see pie chart, right; updated chart here).

It is worth pausing to consider exactly why this is problematic. It is not only that there exist fewer opportunities for high-profile female academics to speak than there should be – though that is an important issue. A more pervasive reason why fewer female speakers is a problem is that the resultant academic environment is hostile to other female academics – particularly junior attendees who, realistically, do not have as much luxury in limiting their participation. For female academics to consign themselves to only “fair” conferences seems to then work somewhat against the intended positive action, since even fewer women end up being represented than there currently are. Female junior attendance, I would bet, will largely remain the same since they cannot professionally afford to restrict themselves. The result is that they are attending conferences with even less female representation than there would have otherwise been, and encountering a more hostile and male-dominated environment.

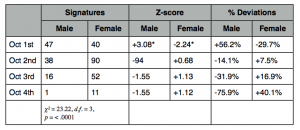

A further point of concern is that, as is fairly typical of feminist campaigns, there seems to be bit of a trend for the loss of interest from male academics over a relatively short space of time (see table, left). Is it reasonable, then, to expect that a majority-female abstention will ignite structural change to remedy this situation? I am inclined to believe that it isn’t. The idea that women should opt out of speaking at conferences in order to pressure them into organisational change is questionable precisely because their contribution is already valued less than that of their male counterparts. Given this bias, withheld participation by women may have much less impact on conferences than desired, particularly at those events which are often currently all-male anyway. If we still want to claim that a boycott is a desirable means of effecting change in this instance (and I’m not entirely convinced that it is), I’d venture that it would be significantly more effective if it comprised a male majority. An additional improvement would be to compile a list of conferences with a poor track record for a focused boycott that people could commit to, rather than relying on their subjective assessment. This would be an improvement not least because leaving the onus on the individual to decide how to behave under the obligation of this commitment (combined with the lack of a concrete goal/measure of success) makes the chances of material change rather slim indeed.

Given what we already know about women’s political representation, I believe a more effective goal is to implement change at an explicitly organisational level. As an example off the top of my head, petitioning for a requirement that established conferences declare their level of complicity with a set of fairness provisions might be more promising. This allows others to judge fairness more transparently (and less subjectively) while simultaneously giving high visibility to this issue as a matter of course. This kind of approach strikes me as somewhat more hopeful in making fair representation a standard consideration of conference organisers, both now and in the future. One barrier to this is that there isn’t, to my knowledge, a central body for the registration of academic conferences or an ombudsman-type overseer that could enforce such a requirement. Given that the academy has proven itself unable to make equity provisions, perhaps one should be instated. At any rate, this is still by no means enough; if we can learn anything from the political sphere it’s that there has to be a material downside to non-compliance beyond disapproval (or lack of votes) from the constituency.

That this conversation has been opened and circulated around the interdisciplinary research community is a very positive step in the right direction. Further thinking on how we can make material changes to structural inequity is both crucial and timely; any and all discussion on this is a Good Thing. I know I’m not alone in hoping that signing this commitment is not the beginning and end of the research community’s action toward gender equity.

“As an example off the top of my head, petitioning for a requirement that established conferences declare their level of complicity with a set of fairness provisions might be more promising. This allows others to judge fairness more transparently (and less subjectively) while simultaneously giving high visibility to this issue as a matter of course.” — Spot on. It’d be nice to see the petition gain some traction and lead to more effective action in limiting this sort of structural inequity. But, yeah, I agree that we’ll need a stronger regulatory framework in place if anyone is going to start taking such changes seriously.

Dan Sperber and I are glad to see the Commitment to gender equity at scholarly conferences receive such a thoughtful discussion. We have a few comments.

First, there are some notable similarities in the roles of women and men with respect to the commitment. A) As organizers, both men and women commit to doing their best to ensure a fair and balanced set of invitations. Markedly imbalanced conferences can occur whether organizers are all-male, all-female, or mixed male and female: both sexes are likely to think of men first when considering possible speakers. The Q and A (http://forgenderequityatconferences.blogspot.fr/) describes what counts as a good faith effort. B) As invited speakers, both men and women commit to enquiring about what efforts are being made to invite women. Neither men nor women commit to turning down invitations if the organizers have made good faith efforts. By accepting an invitation to a conference that is likely to be imbalanced, a woman automatically helps the organizers create a more balanced program in areas where men dominate the podium and a man has the same role in areas where women dominate the podium. Both women and men can suggest speakers of the underrepresented sex. The difference comes about because in most of the conferences that are at issue, men are more likely to be invited speakers. But the roles in principle are the same.

Second, we think that most of the signers (so far) are women because the relative paucity of women invited speakers carries a different signal to women than to men. To women it carries the implicit signal that they don’t belong but to men it is neutral. When college women who are interested in science see a video with markedly more men than women at a science conference, they show elevated physiological vigilance and less feeling of belonging, in comparison to men who see the same video and in comparison to women and men who see a balanced video [Murphy, M. C., Steele, C. M., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Signaling threat: How situational cues affect women in math, science, and engineering settings. Psychological Science, 18, 879-885].

Third, your suggestion that established conferences commit to fairness is terrific! We have also received the suggestion that universities that host conferences commit to fairness, as could governmental and cross-national governmental agencies that sponsor conferences. We realize that institutional commitments to fairness would be difficult to implement, since what counts as fairness will differ. But it would make the issue a prominent one, and fairness would at least be discussed even if not easily achieved.

Thanks so much for reading and for commenting, Virginia. And thank you for your efforts; that you’ve brought some visibility to this issue with a view to change is important and encouraging.

“Neither men nor women commit to turning down invitations if the organizers have made good faith efforts.” This is as I understood it, and I support the idea that conferences ought to be pressured into equitable representation. Since the current status quo (and the root of this action) is a crisis in female representation, I’ll be speaking within this context henceforth.

The problem is that women turning down invitations is unlikely to be a penalty-factor for conferences that already devalue female contributions. If it is the case that “by accepting an invitation to a conference that is likely to be imbalanced, a woman automatically helps the organizers create a more balanced program”, this ought to be specified and highlighted; the commitment itself only proposes that participation be conditional on whether the organisation has been fair. This doesn’t communicate that a member of the underrepresented group needn’t boycott, by virtue of belonging to that group.

If this is the intended action, I think it’s crucial that this is clarified. I would strongly agree with such an amendment. The truth is that men are currently benefitting from being given elevated consideration over women. If this is going to change from the bottom-up (ie, through boycott/participation pressure), then the uncomfortable fact is that it must happen by men relinquishing this benefit. Past evidence from the women’s liberation movement puts the chances of this at slim-to-none. Rather, it must be enacted from the top-down.

“We think that most of the signers (so far) are women because the relative paucity of women invited speakers carries a different signal to women than to men.” No doubt this is true. However, the reasons why women comprise the majority of feminist actions are somewhat orthogonal; it is always the case that the groups affected are the ones who make up the movements representing their interests. The question I was trying to ask above was, given that we can be sure women will care more about participating in this action, is a boycott strategy the best use of their commitment? That they are the ones devalued by the current status quo means that using their numbers for a boycott strategy is unlikely to have the desired impact. However, using these numbers to rally for structural change (such as instantiating regulatory requirements and sanctions) may be preferable.

“Your suggestion that established conferences commit to fairness is terrific!” Thank you very much, and thank you for continuing the conversation that your action has instigated. The main point I wanted to highlight was that we should now think about how to make it detrimental for conferences not to work toward equity. Sanctions for non-compliance are the only effective measure for female representation in other domains, where voluntary commitments have repeatedly failed. As you said, implementing institutional-level requirements is difficult, but a worthwhile (and I would argue, essential) goal if we hope to make any material changes that endure over time.