A large part of human humour depends on understanding that the intention of the person telling the joke might be different to what they are actually saying. The person needs to tell the joke so that you understand that they’re telling a joke, so they need to to know that you know that they do not intend to convey the meaning they are about to utter… Things get even more complicated when we are telling each other jokes that involve other people having thoughts and beliefs about other people. We call this knowledge nested intentions, or recursive mental attributions. We can already see, based on my complicated description, that this is a serious matter and requires scientific investigation. Fortunately, a recent paper by Dunbar, Launaway and Curry (2015) investigated whether the structure of jokes is restricted by the amount of nested intentions required to understand the joke and they make a couple of interesting predictions on the mental processing that is involved in processing humour, and how these should be reflected in the structure and funniness of jokes. In today’s blogpost I want to discuss the paper’s methodology and some of its claims.

Category: Science News

Spontaneous Imitation of Human Speech

Lately, there have been a string of news articles regarding animals imitating human speech sounds. First, there was an account of the nine year-old beluga whale named NOC who was recorded making unusually low, clipped bursts of noise. Then, today, news from the University of Vienna was reported of an asian elephant named Koshik using his trunk to imitate Korean words. Koshik does attempt to match both the pitch and timbre of the human voice, though the researchers doubt there is any meaningfulness to his phrases beyond an attempt at social affiliation.

The more interesting aspect of NOC’s speech is that, unlike the dolphins that are trained to imitate human noises or computer generated whistles, it is the first recorded spontaneous imitation of human speech. Similarly, the marine animals previously studied were raised primarily in captivity. NOC is not only a wild beluga whale, but his speech was also recorded in the wild. The study, published in Current Biology, can be found here (only the abstract is available for free).

Links

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/11/121101121534.htm

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-20026938

Sam Ridgway, Donald Carder, Michelle Jeffries, Mark Todd. Current Biology – 23 October 2012 (Vol. 22, Issue 20, pp. R860-R861)

Angela S. Stoeger, Daniel Mietchen, Sukhun Oh, Shermin de Silva, Christian T. Herbst, Soowhan Kwon, W. Tecumseh Fitch. “An Asian Elephant Imitates Human Speech.” Current Biology, 2012; DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.022

Higgs Boson and Big Data

It’s not about cultural evolution, but I think most people who have even a passing interest in science are gearing up to welcome Higgs Boson to the elementary particle party. Anyway, here’s a nicely put together video on explaining what the Higgs Boson is and why its discovery is significant:

The Higgs Boson Explained from PHD Comics on Vimeo.

There’s also a more general point about needing to gather a huge amount of data (15 petabytes a year — enough to fill more than 1.7 million dual-layer DVDs a year) to find the very small effect size that is predicted for the Higgs Boson. In itself, data of this magnitude will likely come with significantly more noise, which means physicists have needed to develop well-defined statistical methods (they even have their own statistics committee). It really is a massive achievement for modern science.

Language Evolution and Levels of Explanation

A somewhat contentious debate among the behavioural sciences is currently underway concerning Mayr’s division of causal explanations in evolutionary theory. Here I’m going to give you a brief rundown of two papers in particular, before I chip in my two-cents about how other insights from the theoretical literature can inform this debate. It seems the discussion is just getting started with respect to cultural evolution, so it’d be interesting to hear other peoples’ comments from either camp.

Over the years, evolutionary theorists have tried to make logical divisions between the kinds of things we can ask about, with a view to making it clear what exactly scientific studies can tell us. A dominant paradigm dividing two levels of causation for biological features we see in the world is Mayr’s distinction between ultimate and proximate causes. Ultimate causation explains the proliferation of a trait in a population in terms of the evolutionary forces acting on that trait. For example, peahens that prefer peacocks with larger tails (an honest signal of fitness following the handicap principle) will have stronger or more successful offspring, and so this preference proliferates along with larger peacock tails. Proximate causation uses immediate physiological and environmental factors to explain a particular peahen’s penchant for a large-tailed peacock in a mate choice trial, where the signal of the peacock’s large tail elevates the hormone levels in the peahen and copulatory behaviour ensues. Although the behaviour in both of these examples is the same, the levels of explanation are based on different sets of factors.

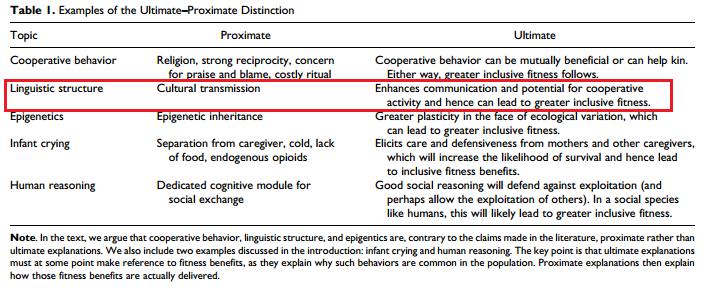

In Perspectives on Psychological Science last year, a paper by Scott-Phillips, Dickins and West voiced some concerns about these two levels of causation being conflated in the behavioural sciences. In particular, they addressed instances where proximate explanations of traits are being framed as ultimate ones. The paper points specifically to studies of the evolution of cooperation, transmitted culture and epigenetics to illustrate this. Regarding the evolution of cooperation, they point to an instance where ‘strong reciprocity’ (an individual’s propensity to reward cooperative norms and sanction violation of these norms) is purported to be an ultimate explanation of why humans cooperate, rather than a proximate mechanism that enables such cooperation.

Among the examples was the feature of linguistic structure (see table 1 from paper above), where several studies pointed to the cultural transmission process as an ultimate explanation of linguistic structure. They suggest that cultural transmission constitutes a proximate process, because it gives the means by which linguistic structure is expressed – and this is how cultural transmission contributes to what the linguistic structure looks like. One analogy might be that the vibrating of my particular vocal cords is a proximate mechanism giving rise, in part, to how my voice sounds, rather than an ultimate explanation of why I vocalise. Since an ultimate account must suggest how a trait contributes to inclusive fitness in order to explain its prevalence in humans, they uncontroversially venture that the ultimate rationale for the ubiquity of linguistic structure is that it greater enables communication (and therefore increases inclusive fitness by enabling cooperative activity).

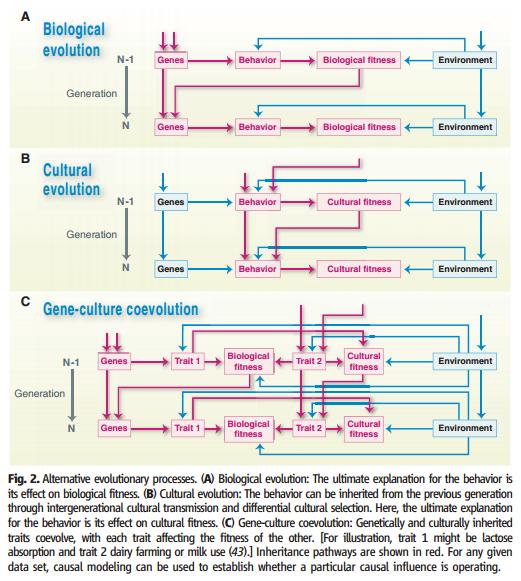

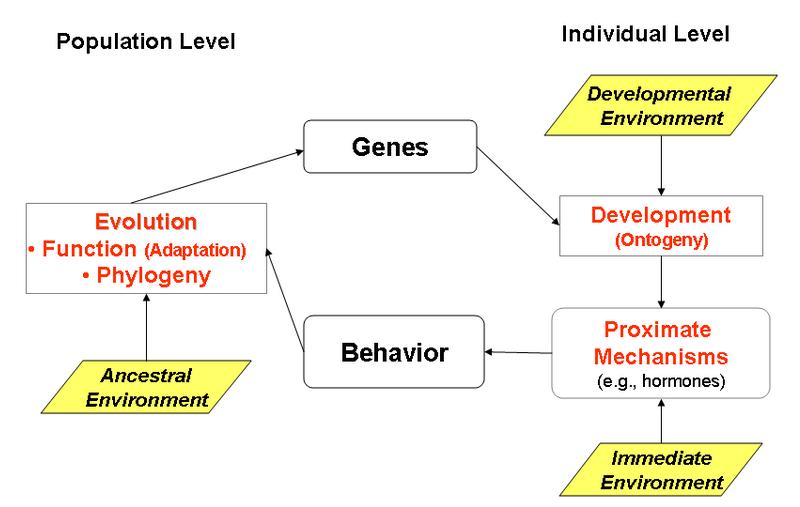

An opposing view was later published in Science by Laland, Sterelny, Odling-Smee et al., who suggest that the use of Mayr’s division of ultimate and proximate causation is not helpful to all evolutionary investigations, and even hampers progress. The grounds for rejecting Mayr’s paradigm seem to lie largely in what Laland et al. term “reciprocal causation”. That is, that “proximate mechanisms both shape and respond to selection, allowing developmental processes to feature in proximate and ultimate explanations”. After aligning proximate explanations with ontogeny and ultimate explanations with phylogeny, they suggest that what we may have called ultimate and proximate features are no longer sharply delineated, and that these reciprocal processes mean that the source of selection sometimes cannot be separated. They present an idea from the field of evolutionary-developmental biology that, if a developmental process makes some variant of a trait more likely to arise than others, then this proximate mechanism helps to construct an “evolutionary pathway”.

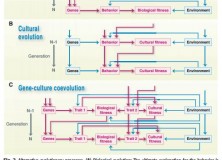

The paper also highlights developmental plasticity, and gene-environment interaction more broadly (see fig. 2 from paper, above), as a process where reciprocal causation offers an evolutionary explanation conceptually comparable to ultimate causation. Talking specifically on the topic of linguistic structure, they present the debate about whether specific design features of language are attributable to biological or cultural evolution. The paper points out that cultural evolution determines features of linguistic structure – for example, word order – and that the existing word order determines that of future speakers. Indeed, at the Edinburgh LEC we know that transmission by iterated inductive inference under general conditions can explain particular structures in languages. That cultural evolution determines the variation between languages, Laland et al. say, provides evidence that it is an evolutionary force comparable to natural selection (and, therefore, ultimate explanation).

What follows is a collection of my thoughts on the matter, which are (spoiler alert) largely in support of the Scott-Phillips et al. paper. I hope others more experienced in cultural evolution studies than I will contribute their perspective.

It seems to me that there are a few assumptions made in the Laland et al. paper that are not quite in line with how Mayr himself understood the paradigm. Perhaps much can be learned from this debate’s previous incarnation, when Richard C. Francis made similar arguments against the ultimate/proximate distinction in 1990. In his critique, he equated ultimate causation with phylogeny and proximate causation with ontogeny – an approach that was rebuked by Mayr in 1993, who made the point that “all physiological activities are proximately caused, but is a reflex an ontogenetic phenomenon?”. Mayr’s response is actually rather unhelpful in addressing the arguments fully, and this statement is particularly dense. But what he is getting at here is the idea that interaction with the environment that gives rise to adaptive behaviours (such as recoiling instantly from a hot stove) is itself subject to selection, and thus constitutes a proximate explanation of causation. Relatedly, he points out that most components of the phenotype are indeed the result of genetic contribution and interaction with the environment, which has been successfully explored in biology within the traditional theoretical paradigm.

A perhaps more nuanced account of how we can divide the possible explanations of biological phenomena is offered by Tinbergen in his “four questions”, where ultimate explanations are further subdivided into Function (concerning the adaptive solution to a survival problem favoured by natural selection) and Phylogeny, which is a historical account of when the trait arose in the species, and importantly includes processes other than natural selection that give rise to variation – such as mutation, drift and the constraints imposed by pre-existing traits (see blind spot example below). Proximate explanations are further split into Mechanism (immediate physiological/environmental factors causal in how the trait operates in the individual) and Ontogeny (the way in which this trait develops over the lifetime of the individual). As a simple example, here is the paradigm applied to a trait like mammalian vision that I lifted from Wikipedia:

Ultimate

Function: To find food and avoid danger.

Phylogeny: The vertebrate eye initially developed with a blind spot, but the lack of adaptive intermediate forms prevented the loss of the blind spot.

Proximate

Causation: The lens of the eye focuses light on the retina

Ontogeny: Neurons need the stimulation of light to wire the eye to the brain within a critical period (as those awful studies of blindfolded kittens illustrated).

A schematic below, adapted from Tinbergen (1963) shows how these levels of causation may interact with one another, which appears to communicate something roughly comparable to the importance Laland et al. place on “reciprocal causation” in the formation of adaptive variants:

Applied to the debate outlined above, it would seem that there is no apparent reason that a process of gene-environment interaction – including the cultural environment – can’t itself be subject to selection, or that developmental plasticity itself is not an adaptation in need of an ultimate explanation. It has long been the case that behaviour is no longer understood as either “nature” or “nurture”, but gene-environment interaction, with varying levels of heredity. The “reciprocal causation” suggested in Laland et al.’s paper, is (as they point out) very common in nature; feedback loops are uncontroversial proximate processes in biology. That a proximate process may give rise to a dominant variant of a trait in a population does not explain why it is adaptive, and this points to another problem with the proposing the abandonment of Mayr’s paradigm: a logical division of levels of explanation doesn’t seem to be the sort of thing that can be rendered outdated by empirical evidence. Indeed, claims about the particulars of traits and processes (and languages) themselves are a matter for empirical data – but the theoretical issue about the level of explanation that data is useful for does not itself seem to be subject to empirical findings.

The finding that a proximate process such as cultural transmission gives rise to a trait that is prolific in a population is itself exciting and surprising, and even shows us that the pressure for making language easier to learn gives us adaptive languages to learn; however, it could be argued that it is this process that is adaptive, and that the reason why humans so heavily rely on this process is an ultimate explanation.

One way of resolving these two perspectives may be to place cultural processes that give rise to variation at the level of what Tinbergen labels Phylogenetic (one subset of ultimate) explanation, as it concerns processes which produce some heightened frequency of traits over a language’s history. An explanation at the level of Phylogeny still must make recourse to natural selection at some point, since variants that result from mutation or drift are retained because of their adaptive value (or an adaptive trade-off). This approach may be a problem for the current understanding, which holds that the features resulting from cultural processes are themselves adaptive and therefore comparable to what Tinbergen labels Function.

The problem with this is that calling particular structures of language ‘adaptive’ obscures what it is about Language that is actually being selected for. To flesh out what I mean, I think it’s useful to consult Millikan’s (1993) distinction between Direct Proper Function and Derived Proper Function (… bear with me, it’ll be worth it, honest). The Direct Proper Function of a given trait T can be thought of as a “reproduction” of an item that has performed the exact same adaptive function F, and T exists because of these historical performances of F. Sperber and Origgi (2000) use the illustrative example of the heart, where the human heart has a bunch of properties (it pumps blood, makes a thumping noise, etc), but only its ability to pump blood is its Direct Proper Function. This is because even a heart that doesn’t work right or makes irregular thumping noises or whatever, still has the ability to pump blood. Hearts that pump blood have been “reproduced through organisms that, thanks in part to their owning a heart pumping blood, have had descendents similarly endowed with blood-pumping hearts”.

The Derived Proper Function, however, refers to a trait T that is the result of some device that, in some environment, has a Proper Function F. In that given environment, F is usually achieved by the production of something like T. If I unpack this idea and apply it to language, we can understand it as the acquisiton and production of a device that, in this environment, leads to, say, a particular SVO language, T. The Proper Function of adaptive communication is performed by T in this case, but could also be performed by any number of SOV, VSO, etc Ts in other cases. In other words, the Proper Function of this language is not the word order itself, but communication. The word order is the realisation of this device that is reproduced because of the performance of T in a particular environment, but does not necessarily lead to T in the next incarnation of that device (i.e. My child, if born and raised in Japan, will speak Japanese). We see, then, that a proximate process resulting in what a particular language spoken by a given population looks like does not necessarily speak to the evolutionary function. In other words, it is the device that allows the performance of Language that is adaptive, not the individual language itself.

One question being asked in the study of cultural transmission is why a particular language looks like it does, while we also know that there are 6000 different versions that perform the same (ultimate) function. I would even argue that asking how proximate processes shape languages is actually the most exciting and interesting avenue of inquiry precisely because it’s so blindingly obvious what the adaptive function of language is. But perhaps the value in this endeavour is somewhat neglected, in part, because of the same impression that Francis (1990) had: “the attitude, implicit in the term ultimate cause, [is] that these functional analyses are somehow superordinate to those involving proximate causes” which would be a shame. It seems to me that the coarse grain of ultimate vs proximate perhaps doesn’t do enough to help complex proximate study to position itself in the wider theoretical framework, and the best way to proceed from this might be to couch explanation in terms of Function, Phylogeny, Ontogeny and Mechanism. I think more fine-grained terminology grants us more explanatory power, in this case.

A final question in this debate that came up too many times during discussions with the LEC is: what does keeping the traditional paradigm “buy us”? Well, the first answer to this is consilience with one of the most successful and robust theories in science. The same sentiment has been communicated by Pinker and Bloom (1990), who said: “If current theory of language is truly incompatible with the neo-Darwinian theory of evolution, one could hardly blame someone for concluding that it is not the theory of evolution that must be questioned, but the theory of language”. Part of the reason this debate may have arisen is that studies of cultural evolution have used evolutionary theory as an incredibly fruitful way of analysing cultural processes, but additional acknowledgement about how cultural adaptation is different to biological adaptation may be necessary. This difference is an aspect of Laland’s paper (shown in Fig 2) that I think is important, as it’s part of the reason that more nuanced frameworks for cultural evolution are now needed. Without this widespread acknowledgement, cultural evolution may be considered an extension of biological evolutionary theory instead of a successfully applied metaphor. It seems to me that the side of this debate one falls on is well predicted by whether one subscribes to the former interpretation of cultural evolution or the latter.

Knowing which level of explanation current work pertains to is a valuable part of evolutionary exploration, and abandoning this in favour of an approach where proximate processes are explanatory ends to themselves may mean the exploration of Function and Phylogeny may suffer. That said, it is telling, I think, that even in seeking to abandon the proximate/ultimate distinction, we must still exploit this existing terminology in order to explain such a position. That natural selection has explained countless adaptations in all living things is certainly not trivial, and to reject the theory giving rise to ultimate explanations as they’re currently defined is to reject this fundamental aspect of evolutionary theory. The big problem seems to be that we’re coming to understand proximate processes as so elaborate and complex, that a more nuanced framework is needed to deal with the dynamics of those processes. I reckon, however, that such a framework can be developed within the traditional paradigms of evolutionary theory.

References

Francis, R.C. (1990) – “Causes, Proximate and Ultimate” Biology and Philosophy 5(4) 401-415.

Laland, K., Sterelny, K., Odling-Smee, J., Hoppitt, W. & Uller, T. (2011) – “Cause and Effect in Biology Revisited: Is Mayr’s Proximate-Ultimate Distinction Still Useful?” Science 334, 1512-1516.

Mayr, E. (1993) – “Proximate and Ultimate Causations” Biology and Philosophy 8: 93-94.

Millikan, R. (1993) – White Queen Psychology and Other Essays for Alice, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Pinker, S. & Bloom, P. (1990) – “Natural language and natural selection” Behaviour and Brain Sciences 13, 707-784.

Scott-Phillips, T. Dickins, T. & West, S. (2011) – “Evolutionary Theory and the Ultimate-Proximate Distinction in the Human Behavioural Sciences” Perspectives on Psychological Science 6(1): 38-47.

Sperber, D. & Origgi, G. (2000) – “Evolution, communication and the proper function of language” In P. Carruthers and A. Chamberlain (Eds.) Evolution and the Human Mind: Language, Modularity and Social Cognition (pp.140-169) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tinbergen, N. (1963) “On Aims and Methods in Ethology,” Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie, 20: 410–433.

The QHImp Qhallenge: Working memory in humans and Chimpanzees

Do you have a better memory than a chimp? Tetsuro Matsuzawa demonstrated the amazing working memory abilities of Chimpanzees, but maybe humans can be just as good, with enough practice. Justin Quillinan and I present the Quick-Hold Improvement Challenge (or QHImp Qhallenge). Play our game and find out if you can beat a chimpanzee.

Play the game here.

You can see the results update live here. Results so far are tantalizing: Replicated Typo’s very own James Winters has already reached the Ayumu benqhmark (9 numbers viewed for only 209 milliseconds)!

Background

Tetsuro Matsuzawa presented his work on chimpanzees in a plenary talk at Evolang. Matsuzawa covered several very interesting experiments and findings, including an experiment into the working memory of chimpanzees. Ayumu is a chimpanzee who was trained to recognise Arabic numerals on a touch-screen and press them in sequence. The most impressive aspect was that Ayumu could complete the task even when the numbers were only displayed for 210 milliseconds before being masked (the ‘eidetic memory task’ or ‘limited-hold’ memory task, Inoue & Matsuzawa, 2007):

You can see more videos of this at the Friends and Ai website.

Continue reading “The QHImp Qhallenge: Working memory in humans and Chimpanzees”

Social networks and Cooperation

A new paper in Nature, by Apicella, Marlowe, Fowler & Christakis was published today. It hypothesises that social network structure may have been present in early human history, and this structure may account for the emergence of cooperation.

A new paper in Nature, by Apicella, Marlowe, Fowler & Christakis, was published today. It hypothesises that social network structure may have been present in early human history, and this structure may account for the emergence of cooperation. The study used data from the Haza people of Tanzania, who presumably already have cooperation, so I’m not sure what data they’re using to back up claims of emergence. I can’t read the article because I don’t have institutional access any more, so I’d be keen to hear thoughts others have.

Here’s the abstract:

Social networks show striking structural regularities, and both theory and evidence suggest that networks may have facilitated the development of large-scale cooperation in humans. Here, we characterize the social networks of the Hadza, a population of hunter-gatherers in Tanzania. We show that Hadza networks have important properties also seen in modernized social networks, including a skewed degree distribution, degree assortativity, transitivity, reciprocity, geographic decay and homophily. We demonstrate that Hadza camps exhibit high between-group and low within-group variation in public goods game donations. Network ties are also more likely between people who give the same amount, and the similarity in cooperative behaviour extends up to two degrees of separation. Social distance appears to be as important as genetic relatedness and physical proximity in explaining assortativity in cooperation. Our results suggest that certain elements of social network structure may have been present at an early point in human history. Also, early humans may have formed ties with both kin and non-kin, based in part on their tendency to cooperate. Social networks may thus have contributed to the emergence of cooperation.

Never mind language, emotions are in a category of their own

A new paper in the journal ‘Emotion’ has presented research which has implications for the evolution of language, emotion and for theories of linguistic relativity.

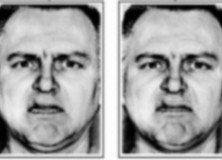

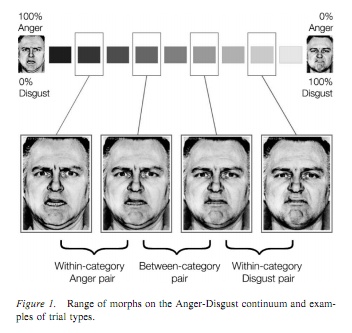

A new paper in the journal ‘Emotion’ has presented research which has implications for the evolution of language, emotion and for theories of linguistic relativity. The paper, entitled ‘Categorical Perception of Emotional Facial Expressions Does Not Require Lexical Categories’, looks at whether our perception of other people’s emotions depend on the language we speak or if it is universal. The results come from the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics and Evolutionary Anthropology.

Human’s facial expressions are perceived categorically and this has lead to hypotheses that this is caused by linguistic mechanisms.

The paper presents a study which compared German speakers to native speakers of Yucatec Maya, which is a language which has no labels which distinguish disgust from anger. This was backed up by a free naming task in which speakers of German, but not Yucatec Maya, made lexical distinctions between disgust and anger.

The study comprised of a match-to-sample task of facial expressions, and both speakers of German and Yucatec Maya perceived emotional facial expressions of disgust and anger, and other emotions, categorically. This effect was shown to be just as significant across the language groups, as well as across emotion continua (see figure 1.) regardless of lexical distinctions.

The results show that the perception of emotional signals is not the result of linguistic mechanisms which create different lexical labels but instead shows evidence that emotions are subject to their own biologically evolved mechanisms. Sorry Whorfians!

References

Sauter DA, Leguen O, & Haun DB (2011). Categorical perception of emotional facial expressions does not require lexical categories. Emotion (Washington, D.C.) PMID: 22004379

Support EVOLUTION: THIS VIEW OF LIFE

I just stumbled across this really cool project over at kickstarter. It’s for a website, Evolution: This View of Life, which is being run by the well-known evolutionary theorist, David Sloan Wilson. Here is the pitch from Sloan’s blog:

EVOLUTION:THIS VIEW OF LIFE is a new online general interest magazine in which all of the content is from an evolutionary perspective. It includes content aggregated from the internet and new content generated by a team of editors, all professional evolutionists, representing eleven subject areas. The editors work for free, in the same spirit as editors of academic journals. Their expertise enables EVOLUTION:THIS VIEW OF LIFE to feature evolutionary science in action, as stimulating for the professional as for the general public.

To help launch the magazine, we are trying to raise $5000 through Kickstarter, which will be used to support the central office and purchase equipment for video and audio recording. Contribute $50 or more and get a cool t-shirt with this logo designed by illustrator Kevin Cannon. Pledge $80 or more and we’ll record a videocast with you, so that you can share what evolution means to your view of life.

Does a Smart Phone make Smart Science?

A new paper in plos one, published today, has shown that experiments on human cognition needn’t be confined to the lab.

Experiments on human cognitive abilities, such as language, often rely on testing small and homogeneous groups of volunteers (mostly undergraduate students) coming to research facilities where they are asked to participate in behavioral experiments. This arrangement is not ideal as your sample will not be representative of the population as a whole and will also be restricted as there is only so many participants that money and time will allow you to get into the lab to be tested.

This new research by Dufau et al. shows that the sampling limitations which laboratory experiments produce can be overcome by using smartphones. Using smart phone technology, data can be collected for cognitive science experiments from thousands of subjects from all over the world.

To illustrate how this can be done the authors carried out a large-scale study using iPhone and iPads. This was a linguistic study looking at people’s ability to distinguish words from similar non-words.

The project, which began in December 2010 has managed to collect data from 4,157 subjects in just 4 months! This can be compared with the English Lexicon Project which acquired a similar volume of data using traditional methods which took more than 3 years.

The data was collected using applications which were produced in seven languages (English, Basque, Catalan, Dutch, French, Malay, Spanish). Smartphones can also support studies in alphabets other than Roman including Chinese, Greek, and Japanese. This creates the opportunity to create large-scale cross linguistic studies without even having to move from behind your desk.

Whilst the example here is linguistic there is every reason that smart phones can be implemented in looking at how universal other areas of cognitive behaviour are. Or even neurosceince and experimental philosophy. I wonder if it would be possible to carry out experiments using transmission chains using smart phones.

However, I do worry that using things like iPhones will have the same problems as using things like mechanical turk, as it means that experimenters will not be able to make sure that participants are carrying out the tasks properly and removes quite a lot of control. Smartphones are also still a luxury and therefore only people within a certain socio-economic class will have smartphones, so maybe these methods may not reach such a wide audience, which seems to be why they’re being proposed in the first place.

The authors of the paper are hailing smartphones “a potential revolution in cognitive science” but only time will tell if this really kicks off!

Reference

Stephane Dufau, Jon Andoni Dun abeitia, Carmen Moret-Tatay, Aileen McGonigal, David Peeters, F.-Xavier Alario, David A. Balota, Marc Brysbaert, Manuel Carreiras, Ludovic Ferrand, Maria Ktori, Manuel Perea, Kathy Rastle, Olivier Sasburg, Melvin J. Yap, J (2011). Smart Phone, Smart Science: How the Use of Smartphones Can Revolutionize Research in Cognitive Science PlosOne, 6 (9) : 10.1371/journal.pone.0024974

The Gestural Repertoire of the Wild Chimpanzee

In the past many studies have been done on the linguistic abilities of trained apes using artifical languages, but what about in the wild?

Catherine Hobaiter and Richard W. Byrne at the University of St. Andrews have carried out a new study looking at the intentional gestures of chimpanzees in the wild.

Whilst it is generall agreed that gestural communication in great apes as seen in the wild is intentional and elaborate and flexible the authors outline that there is still a lot of controversy with regards to interpretation of the system and how the apes acquire it. These questions are hard to untangle when studied in the captive settings of a zoo.

The study presents a systematic analysis of the gestures made by a population of chimpanzees in the wild. 4,397 cases of intentional gesture were recorded in Budongo, Uganda.

These recordings were used to identify 66 gesture types. These gestures were seen to differ between individuals and also between age classes. Regardless of these differences no gesture was used only by one individual. I worried when I first read this as sometime studies identify intentional gestures by using the criteria that the gestures were used in the same context a certain number of times, however, within this study the criteria for intention gesture was as follows:

Audience checking: The signaller shows signs of beingaware of the potential recipients and their state ofattention, e.g. turning to look at the recipient beforegesturing.

Response waiting: The signaler pauses at the end of thecommunication and maintains some visual contact.

Persistence: The production of further gestures, afterresponse waiting and in the absence of a response that in other cases is taken as satisfactory. (In certain circumstances, such persistence might be impossible, for example where an adult carries an infant away; these cases are marked as unable to persist, rather than nopersistence.)

The authors argue that these gestures are not acquired by ‘ontogenetic ritualization’, which is when actions which are performed to reach some goal become ritualised to the point that they can be anticipated from an intial gesture sequence. The authors carried out detailed analyses of two gestures to show that the action elements which the gestures were made up from did not match those of the original actions.

This lack of ontogenetic ritualisation may be down to these gestures being species-typical, or typical across all the great apes. Comparisons made with the recorded gestured of gorillas and orangutans show that chimpanzee overlap with at least 24 gestures which are recorded in all three species. Dr Hobaiter is cited as saying on the BBC story that:

“the gestures that apes use (and maybe some human gestures too) are derived from ancient shared ancestry of all the great ape species alive today.”

The gestures were also able to be used flexibly across contexts and were able to adjust to the audience, for example the chimps were shown giving silent gestures when their audience was attentive and used contact in their gestures when the audience was inattentive.

The paper includes extensive analysis of repertoire size across age groups, contexts each gesture type was used in as well as things like hand position and shape during gestures.

This is the first study of its type using a wild population of chimpanzees. It shows highly intentional use of a species-typical repertoire which seems surprising and certainly contributes evidence relating to the evolution of intentional communication.

Reference